From KERA News:

Medicaid in Texas covers close to 6 million people, everyone from cancer patients to pregnant people to kids across the state. That coverage means people have access to doctor’s appointments, hospital visits, nursing facilities and birth centers, without having to worry about the cost of care, according to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

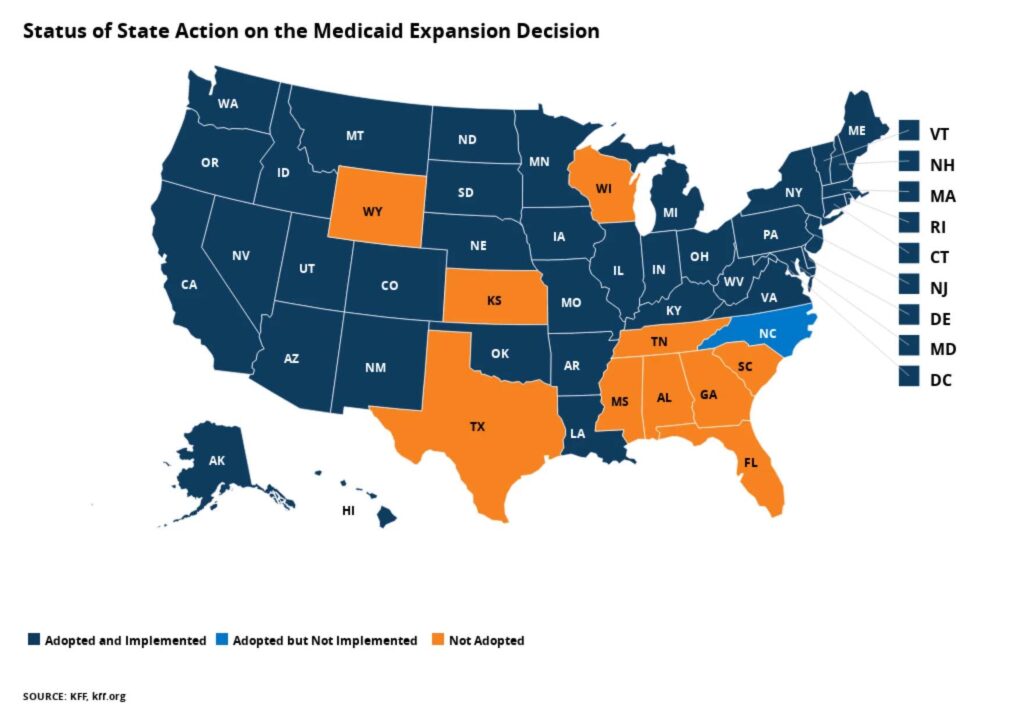

But 13 years after the Affordable Care Act expanded Medicaid, Texas is now one of only 10 states that has yet to adopt it.

Almost a decade of research shows people’s health improves in states with expanded access to care, and about 1.4 million low-income adults would be eligible. So why hasn’t Texas expanded Medicaid?

Impact on health outcomes

Adam Searing, a research professor at Georgetown University, has been working on Medicaid issues at the university since 2014. He said it’s one of the “most studied health policy issues in history” because of the stark differences between states that have expanded coverage and states that have not.

“The idea with Medicaid [is] that the people who are really in the lowest income category can still be able to get decent health coverage, and that has lots of good implications for them and for their ability to work,” Searing said.

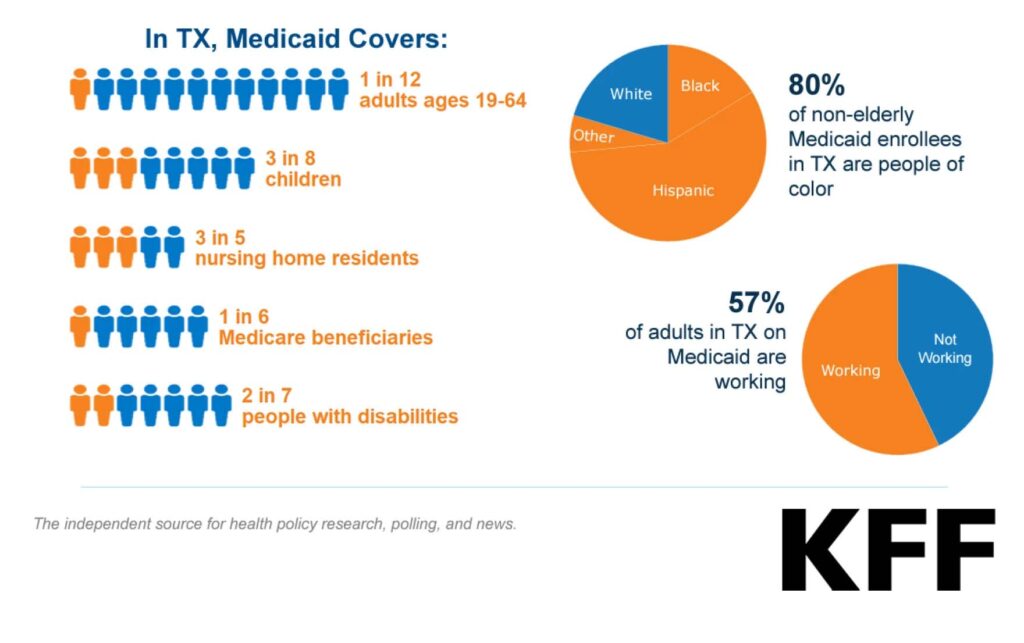

In Texas, Medicaid covers more than 5.8 million people. That’s 17% of the total population of the state.

Kaiser Family Foundation / KFF

Research shows the impact of Medicaid expansion is widespread: People have better dental health and lose fewer teeth to decay; teens have improved access to contraceptives, which reduces their chances of unintended pregnancy; pregnant people have access to postpartum coverage after childbirth for a longer period, which contributes to lower maternal mortality and morbidity rates; and children who age out of the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) are less likely to lose insurance as they become adults.

“By and large, there are just huge benefits to people who get coverage,” Searing said. “Health is a building block for a lot of success, whether it’s in work, family, society, your job.”

Beyond health impacts, people in states that have expanded Medicaid experience less financial pressure. For example, a 2023 study in JAMA showed lower rates of evictions in counties with Medicaid expansion.

“When you expand Medicaid, the increase in financial security for many families goes up significantly,” Searing said. “That means they can make their car payments. They can pay their rent. They can continue to go to the restaurant down the street or buy toys for their kids at the local toy store.

“So, there are all these ripple effects in the economy, too.”

Texas is one of 10 states that has not expanded Medicaid. It also has the highest rate of uninsured people in the country: 21% of Texans are uninsured, in comparison to the national average of 10%.

Kaiser Family Foundation / KFF

Reasons states haven’t expanded Medicaid

Historically, Searing said, arguments against Medicaid expansion fall into two categories: differences in political ideology, and not wanting to grow an already broken system.

“Many legislators in the states that haven’t expanded say, ‘Well, we just don’t feel that the government should be in the in the business of helping provide health coverage for folks, they should get it through their work,’” Searing said. “And I’ve heard legislators say, ‘Well, our Medicaid system is a government system, it doesn’t work very well. And we don’t think it can take more people being in the system.’”

The eligibility requirements for Texans under Medicaid are some of the strictest in the United States: For parents and caretakers of kids who are covered by Medicaid, a family of four with two parents has to make at or below $285 a month to be eligible. In comparison, the same family in Tennessee can make at or below $1,867 a month and the caregivers can still qualify for Medicaid coverage.

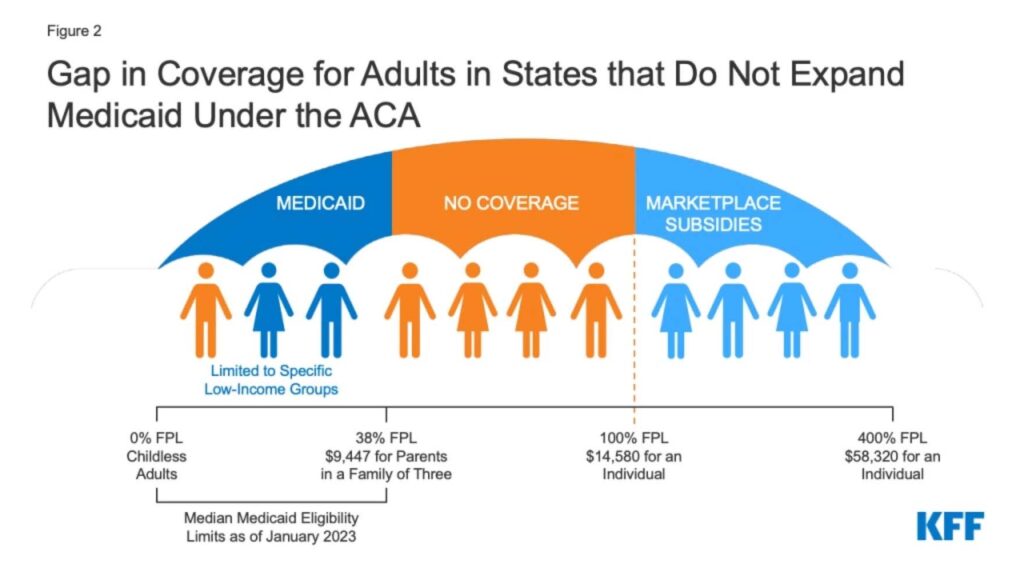

Adults in Texas who aren’t caregivers, pregnant, have a disability or are 65 years or older cannot access Medicaid. They can access insurance through the Affordable Care Act marketplace, but they must make above the federal poverty income level.

According to the advocacy and policy organization Every Texan, “this leaves most working-poor Texas adults uninsured, because [the] state’s Medicaid program is closed to them, and they cannot get sliding-scale ACA coverage[,] either.”

Texas Republicans have opposed Medicaid expansion for years. Back in 2015, Gov. Greg Abbott said “Medicaid expansion is wrong for Texas,” writing in a news release that the program is “already broken and bloated.” Beto O’Rourke, who ran for governor against Abbott in 2022, made Abbott’s refusal to expand Medicaid a key point in his campaign.

Texans called their own hearing to discuss Medicaid expansion at the state Capitol in March. In 2021, Democratic lawmakers introduced bills to expand Medicaid with bipartisan support, but the bills ultimately did not make it into law.

Cindy Ji / Children’s Defense Fund Texas

Most Texans support Medicaid expansion

But most Texans support wider access to health care coverage. A 2020 poll by the Episcopal Health Foundation showed nearly seven in 10 Texans “think the state should expand Medicaid to provide health insurance to more low-income Texans who are uninsured.”

“Texas is a state that has the largest number of people who would benefit from expansion,” Searing said. “When you get down to ordinary people who are trying to live their lives, they are generally very supportive of expansion, regardless of what side of the political spectrum they’re on. So, we really need to focus on the leadership in the states that haven’t expanded. And political leadership is where the roadblocks are.”

He points to North Carolina as an example of a state that recently expanded Medicaiddespite the fact that “for much of the past decade, Republican legislative leaders opposed expanding the Medicaid program to more than 600,000 new recipients.”

Searing said he “took a lot of hope” from seeing previous opponents of expansion discuss the benefits to people like young mothers, students and uninsured children.

If lawmakers in North Carolina, a state with a Democratic governor but “very, very conservative leadership in the state legislature” could change their minds about Medicaid expansion, Searing said other states can, too.

“Even in states like Texas, that have a lot of ideological opposition still, there is this potential for change,” he said. “And I hope eventually that will happen. I think it will.”

Tambra Morrison spoke at the People’s Hearing for Medicaid Expansion at the state Capitol in Austin in March.

Cindy Ji

Impact of not expanding Medicaid on accessing health services

Kailey Horne, a recent graduate who lives outside Houston, knows firsthand the impact of not having insurance. She was on Medicaid as a kid, but lost it when she aged out. She qualified for Medicaid again when she was pregnant, but lost it a few months after she gave birth to her son.

“It just became a cycle of not being able to go to the doctor,” Horne said.

In her twenties, she started having seizures and periods of aphasia, where she had trouble understanding people and responding to them.

“I went probably like three or four years just getting worse,” Horne said. “I knew I needed to go to doctor and figure out what was wrong, but I just didn’t have the means to do so.”

Horne made too much money to qualify for Medicaid at the time but didn’t make enough to afford a plan through the insurance marketplace.

In early 2022, she had a tonic-clonic (grand mal) seizure when she was out at the movies. She fainted and was taken to the hospital, where she was finally diagnosed with epilepsy. She applied for Medicaid again, even though she’d been denied after her pregnancy, because she wasn’t sure how she was going to pay for the cost of her medication or visits to specialists.

Since Texas has not expanded Medicaid, close to 800,000 Texans live in the “coverage gap,” where they make too much money to qualify for Medicaid but not enough to routinely afford other insurance premiums.

Kaiser Family Foundation / KFF

“This time, whenever I applied, it felt a lot more serious,” she said. “This was a very stressful time for me. My life had completely changed. I needed the insurance. It was just this piece of hope that I was holding on to—maybe I can finally get some help if they would just reply to me.”

After a few months of waiting, she was approved. But the whole process made her feel like “a pawn in the health care system, to learn how to navigate all of this stuff when at the same time trying to deal with the life changes that I was having.”

Horne often wonders what her life would have been like if she could have accessed health insurance after her pregnancy, or when she started experiencing seizures for the first time.

“My struggle to get good insurance and to find providers that will accept it, in a way it’s prolonged my recovery, prolonged my success with epilepsy treatment,” she said.

If she could talk to lawmakers, she would encourage them to expand access to Medicaid.

“There are a lot of people in the same gap that I was in,” Horne said. “I was working, and I was bringing in money, but apparently it was too much to qualify for Medicaid. I was also going to school, so I wasn’t able to work full time to qualify for insurance. The eligibility needs to change.”

Meridith McGee speaks at a gathering at the state capitol earlier this year to advocate for Medicaid expansion.

Brie Banks / Children’s Defense Fund Texas

‘It’s a human issue’

State Rep. Julie Johnson, D-Carrollton, co-authored a Medicaid expansion bill in 2021 to try to close this coverage gap in Texas. House Bill 3871 would have established the “Live Well Texas” program, expanding Medicaid access to adults and offering job training and financial assistance.

“Health care is not a Republican or Democratic issue,” Johnson said. “It’s a human issue.”

But in Texas, much like other states, support for Medicaid expansion falls along party lines — Democrats for, Republicans against. Johnson said she and her Senate colleague, Sen. Nathan Johnson, D-Dallas, spoke with Republicans to try to “move the needle” on Medicaid expansion when they first introduced the bill in 2021.

“There’s a lot of Republicans who represent rural Texas whose hospitals are closing,” Johnson said. “They have constituents that have to drive three, four hours to get to the nearest emergency room. They understand the significance of Medicaid expansion to their districts.”

From 2013 to 2020, Texas had the most rural hospital closures in the country, according to a 2020 report by the U.S. Government Accountability Office. The report found that over time, doctors continued to leave areas with hospital closures, giving people even fewer options for care.

Medicaid expansion alleviates some of the reasons for closures by improving “hospital finances by extending coverage to uninsured patients who would otherwise qualify for hospital charity care or be unable to pay their bills,” according to the Kaiser Family Foundation.

Ultimately, nine House Republicans signed on to HB 3871, but the bill failed to pass either chamber. This year, Johnson’s “Live Well Texas” bill didn’t make it out of committee. She said it’s mystifying to her why, with so much evidence on the benefits of Medicaid expansion, Republicans refuse to support it.

“It absolutely makes no sense,” Johnson said. “This is politics. This is an uninformed, far-right Republican base, making a policy decision that is not based in truth, but it’s based in myth, and an inaccurate belief structure.”

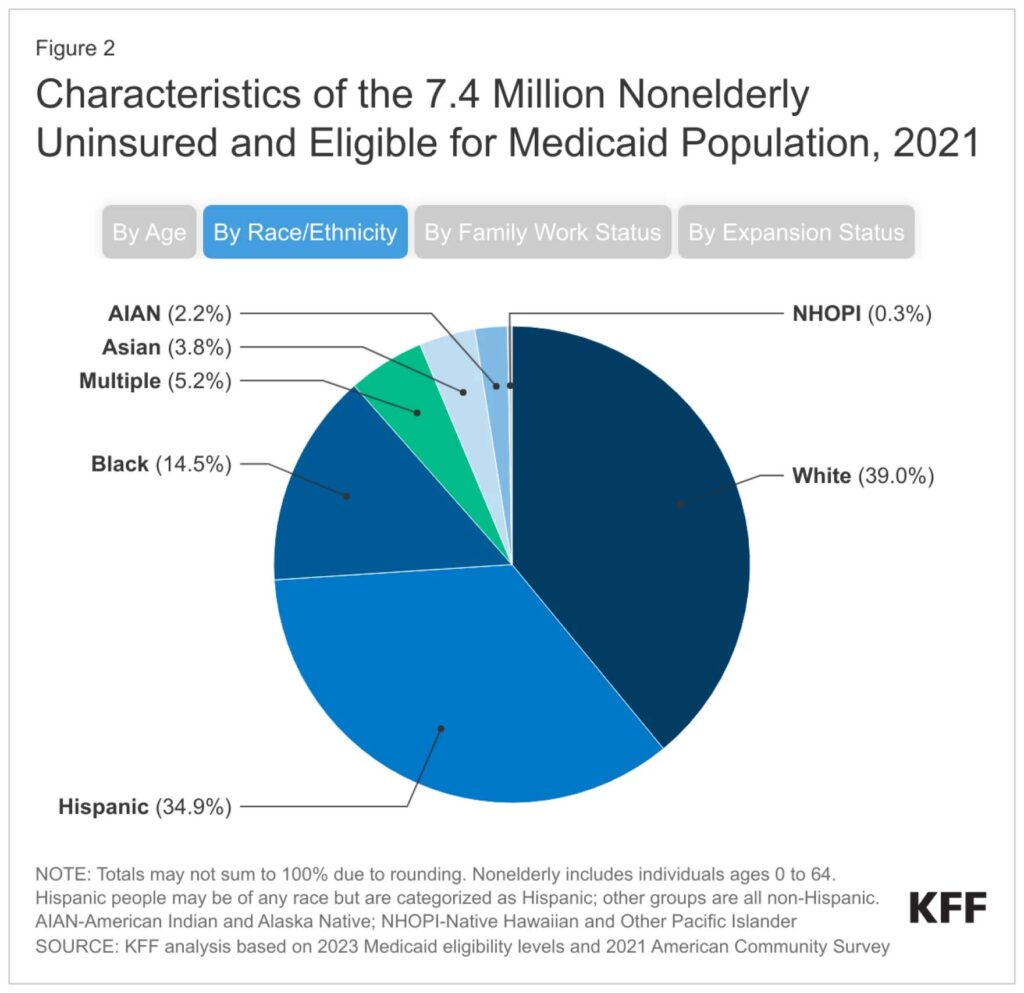

According to a Kaiser Family Foundation brief, 80% of non-elderly Medicaid recipients in Texas are people of color. 57% of adults on Medicaid in Texas are working.

Kaiser Family Foundation / KFF

The state and future of Medicaid in Texas

Policy groups and health associations have long been discussing the benefits of expanding Medicaid in Texas, but the discussion took on new meaning in 2023 as hundreds of thousands of people lost the coverage they had for three years under the federal COVID-19 public health emergency declared in 2020. Continuous Medicaid enrollment under this provision ended March 31.

The groups impacted most likely include kids 19 or older who aged out of the program, new parents, and kids whose families have made more money than the monthly requirements.

But it’s hard to tell exactly who’s been impacted, said Stacey Pogue of the advocacy and policy group Every Texan, because states aren’t required to submit demographic data to the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). Pogue spoke during a press conference in early August on the impact of Medicaid unwinding thus far in Texas.

Before continuous enrollment, pregnant people who recently gave birth would lose Medicaid coverage after two months, which led to higher rates of maternal mortality and morbidity. This year, Texas lawmakers passed HB 12 extending coverage to 12 months postpartum. The law goes into effect Sept. 1.

But Pogue said Texas still must submit a plan to CMS, and have the plan approved before people can access extended coverage.

“What that means is new [parents] anywhere from two to 11 months postpartum are going to start losing coverage in September and October during unwinding, despite HB 12,” she said.

New parents have limited coverage options beyond a year since Texas has not expanded Medicaid.

According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, pregnant people of color are more likely to be uninsured or lose Medicaid coverage after giving birth than other groups.

Kaiser Family Foundation / KFF

According to data from the Texas Health and Human Services Commission, in June, more than 785,000 people who previously had coverage either were now ineligible, their applications were denied, or they had incomplete applications.

Texans Care for Children, an advocacy and policy organization, said in a statement that “the high percentage of procedural denials should be setting off alarm bells.”

“When you see this many procedural denials, it means that the process is not working properly, whether the state is sending renewal information to the wrong mailing addresses or parents are running into bureaucratic delays with the state when they try to renew their children’s health insurance,” said Diana Forester, the director of health policy at the organization.

Since Aug. 1, about 3.8 million people have been disenrolled from Medicaid nationally, according to analysis by the Kaiser Family Foundation. Texas has the largest number of people disenrolled in the country, said Pogue, and it’s only going to get worse as time goes on.

“The problems with eligible folks losing coverage are huge,” she said. “We need the governor to ensure no eligible [person] loses coverage on his watch.”

For Rep. Johnson, now is the time to consider Medicaid expansion. She says it’s about giving more people the chance to live a healthy life.

“When the person you love most on this earth—your child, your parent, your spouse—needs health care and can’t get it, that is very, very frustrating, sad, emotional, and heartbreaking,” Johnson said. “We as a state can do better by our residents, by the people of Texas. Our elected leaders need to step up to the plate and pass Medicaid expansion.”