It’s a story we’ve heard before in recent years: A teacher is pushed out of a job because of their viewpoints.

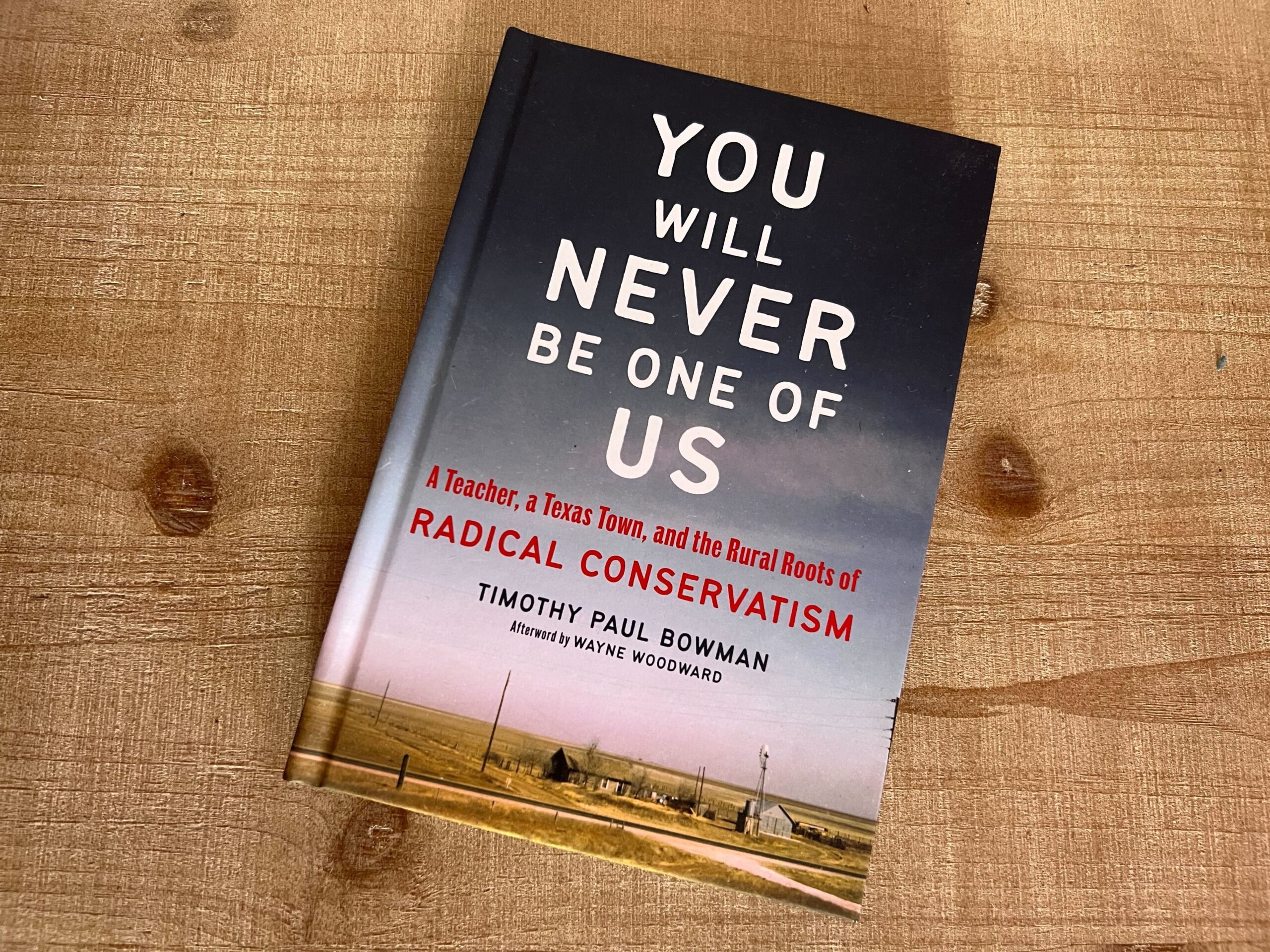

It happened to Wayne Woodward, a popular teacher in the Panhandle during a time of societal reckoning. His story and the court battle that ensued is told in the book “You Will Never Be One Of Us: A Teacher, A Texas Town and the Rural Roots of Radical Conservatism.”

Historian Timothy Paul Bowman is the author of the book and chair of the department of history at West Texas A&M University in Canyon. He spoke with Texas Standard on the parallels between the story and today and what we can hope to learn. Listen to the story above or read the transcript below.

This transcript has been edited lightly for clarity:

Texas Standard: Tell us a little bit more about the person, Wayne Woodward, and where he found himself there in the 1970s.

Timothy Paul Bowman: So Wayne Woodward grew up in Amarillo. He was born in a different part of Texas, but moved here with his mother right around the early 1950s. And he was a young guy who had actually graduated from the institution where I teach now, West Texas A&M University, which back then was called West Texas State University. And he’d gone on to teach and wasn’t a hugely political person, you know. I mean, he had some sympathies with the sixties generation and the hippies and, you know, of course, was someone who grew up questioning racial segregation like a lot of people did in the 1950s and 60s, but was relatively apolitical.

And so in early 1975, he had been teaching at a little community called Hereford, Texas, which is in Smith County, near the state line with New Mexico, and co-founded a local chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union with a local Catholic priest and thought, “this is a great idea. Who doesn’t love civil liberties? My boss, everybody in town will like this” and didn’t really know much about the organization’s history or the right’s negative perception of it. Hence a long battle at the school ensued between him and his principal – a man named Robert Paterson Hughes – and eventually he was let go in the spring of 1975, he felt because of his participation in the ACLU at the local level.

Was there something in particular that precipitated this tension? Was it just the fact that he was, you know, helping to establish the ACLU chapter there, or was there something that seemed to sort of be the spark that ignited that degree of anger?

So he had a few little bumps in the road with the administration at La Plata Junior High School in Hereford – it’s Hereford Middle School now. Back in those days he, you know, had a tendency to question things that he was told. At one point the school administrators wanted him and the other teachers to sign on to a contract stating that they didn’t support the Equal Rights Amendment, which was, of course then being debated and activists hope would be ratified, which would protect gender equality for women. So he spoke up about these things and was sort of a bit of a troublemaker in his own right. But he wasn’t someone who was seen as a threat by local officials, really until the ACLU chapter started.

Unfortunately for Wayne, he started the chapter with a Catholic priest. This is a gentleman named Father Jose Gilligan, who’s unfortunately no longer with us, who ministered to the local migrant labor population. And so, as I explain in the book, the founding of the ACLU was sort of seen as this kind of existential threat to the town that would, you know, bring in organizing efforts for Mexican-Americans, you know, might potentially throw the doors open to the United Farm Workers, led by Cesar Chavez in California, coming in and leading leading strikes in the local agribusiness industry, which was a multimillion dollar prospect in the 1970s already.

Tell us a little bit about what Wayne Woodward’s trial ultimately meant to the Panhandles perception of being, in a sense, sort of removed from… I mean, it’s a rural area, right? And there was a very wide chasm, perhaps even more than we think exists today. Could you say more about what this chapter in local history meant for that aspect of sort of the rural-urban divide?

I think it meant that the outside world was coming crashing in, especially in Hereford, which had kept a lot of these forces at bay and again, led to, you know, people on both sides of the aisle, whether it was in Hereford or in Amarillo or Canyon, sort of digging their heels in even further. You know, the book’s title, “You Will Never Be One of Us,” is this idea that Wayne, even though he grew up in Texas and in Amarillo, he didn’t fit in locally. And that was the message that he constantly received from people who were critical of him. “Your ideas don’t fit. You don’t belong.” At one point, one of his opponents in the case says that, “well, you should be teaching in New York or California, not here. We don’t want these sorts of changes to occur here locally.” But it meant that oppositional politics, if one was a conservative in the 1970s, were no longer something that could be avoided at the local level. There wasn’t this sense of a cohesive political culture that people in the dominant majority, I think, would have liked. And one can imagine that this is a pretty typical story, right? That would have occurred in lots of different locales, whether they lean to the left or lean to the right politically – this idea of, you know, a new person coming in and trying to shake things up and ultimately being rejected and not understanding why.

What do you think it tells us about modern times? Is there a lesson that can be drawn from Wayne Woodward’s experience?

I think that one of the things, to me, that it tells us is that people need to work harder to try to find a middle ground. Interestingly, one of the people who was quite critical of Wayne was a man named Bobby Templeton, who was the editor of the Hereford Brand [newspaper] during the trial for couple of years. And I wasn’t able to track him down while I was writing the book. I didn’t know if he was still living or where he was. And then I, you know, I suddenly got a Facebook message from him someday, which really shocked me. And I read it and he said, “you know, I read your book. It was really interesting. I don’t fully agree with the way that I was portrayed.” And I wrote him back and I said, “you know, it wasn’t my intent to portray you in any type of negative light whatsoever. I just, you know, told what I believed was the truth.” But, of course, you know, history is an interpretive endeavor. And if someone else were to write Wayne’s story, they might write it differently. And really interestingly, what wound up happening after that is Templeton tracked down Wayne. And I’m not sure if they spoke on the phone or if they just exchanged emails, but he apologized to him.

So here he was, you know, this man, nearly 50 years later, who read a book about a chapter in his life – Templeton – and he had some regrets from it. And I was really, really quite touched by that. You know, it made me feel really good and made me think that, you know, maybe there is some hope that people – again, whatever their political affiliation might be – that people, you know, if enough time passes, can look past their differences and try to bridge this divide that’s just everywhere in our country today and has just become absolutely toxic.