They were at the top of Dallas high society in the ’50s and ’60s: Millionaires with private planes, prestigious country club memberships, unlimited credit at Neiman Marcus.

Their bank accounts were often lined with oil money — and many of them were victims. Victims of a character whose exploits seemed ripped from a movie script – slipping over the fences of the city’s finest homes, sometimes dropping in from rooftops and making off with millions in jewels.

The thief was dubbed by the local press as the “King of Diamonds.” The thefts would catch the attention of police the world over, and the crime spree would outlast the tenures of four presidents — from Eisenhower all the way to Nixon.

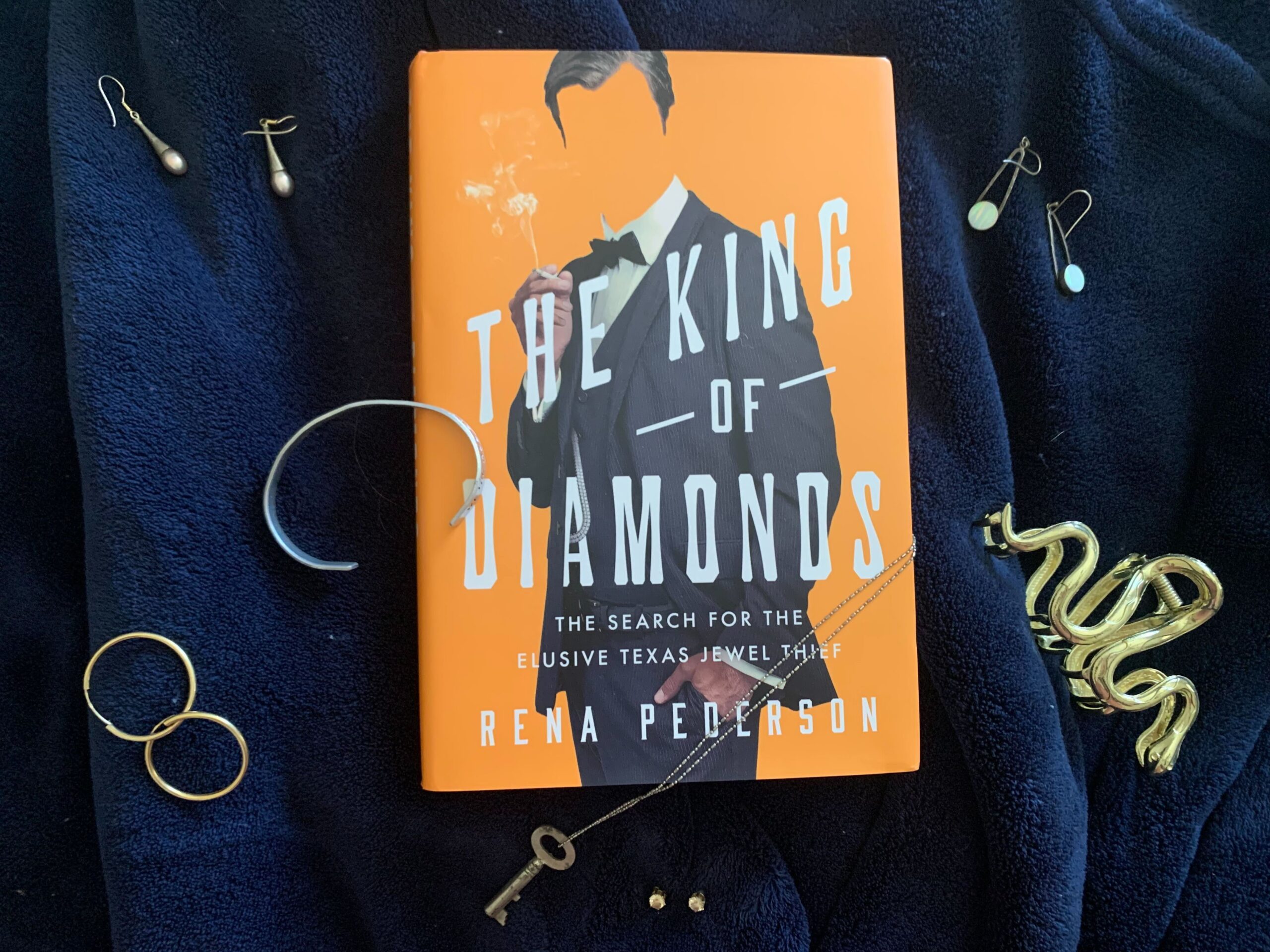

A half a century later, whatever happened to the elusive Texas jewel thief? Author Rena Pederson picks up the trail in her new book, “The King of Diamonds: The Search for the Elusive Texas Jewel Thief,” which just released today.

She called him the “Houdini of jewel thieves.”

“I could make a good case that he was one of the most successful jewel thieves in the country. He stole the equivalent of $6 million in jewels today. And he endured for so many years. I mean, he had a longer career than the Beatles,” Pederson said.

“He preyed on this very small area of Dallas, mostly the suburb of Highland Park in the area known as Preston Hollow. There’s never been another American jewel thief who worked such a compressed area for so long and was never caught.”

The thief’s exploits were defined by his unique style, Pederson said. He was clever and acrobatic, pulling off stunts that puzzled the police.

“He somersaulted out of windows, he climbed onto balconies. He climbed up the side of Jim Ling’s house like a rock climber. And at the time there were security guards patrolling the estate. And they never saw him,” she said.

“He left these interesting clues. There were Ripple footprints from Ripple-soled shoes – probably pull-on galoshes because he often came up creek so nobody would see him. And those were the only clues that the police had. He didn’t leave fingerprints. He probably wore gloves. He only left these little Ripple-sole footprints, but they could never catch him.”

Police had lots of theories about the thief’s position in society, given that he seemed to know when his victims would be out at events and where they kept their best jewels.

“Police eventually figured out that it had to be somebody from the area because he knew where people lived. He knew when they were going out or when they were home. But it didn’t deter him that they were home because he knew they had their jewels out for the social season,” Pederson said.

“He mostly operated from October to March, and he would come in and crawl right by them. He hit Clint Murchison, sometimes described as the richest man in the country, though he was actually number three. He also hit Margaret Hunt, the late Joe Hunt’s daughter. I mean, it was like an honor roll of some of the richest, most successful people.”

Members of Dallas’ high society became increasingly paranoid about the thief’s identity, Pederson said.

“They would go to their balls and go to these big celebrity events, and they would look across the room and they’d go, ‘I think it’s him. I think it’s him.’ And they suspected their friends. They suspected their neighbors. You know, they would say, ‘Well, she doesn’t have enough money to dress like that or he didn’t have any money for that Rolls Royce,’” Pederson said.

“There were at least 60 burglaries, I think probably more than 100 because a lot of people didn’t report it. They wanted to keep it quiet. There were all these suspects – everybody from the valet parkers to the cleaners to the food society columnist to the jewelers.”

Pederson said while writing her book she picked the names that came up the most often as possible suspects and researched those people. Part of the difficulty in catching the thief was that the jewels never turned up for sale that anyone discovered.

“A good supposition would be that organized crime had something to do with it, because they had the connections to get things out of town and overseas before you could test for fingerprints,” she said.

Pederson called the mystery the “ultimate game of Clue,” and the suspicions as to the culprit’s identity caused their own damage.

“A lot of people were harmed by this suspicion, just as there were a lot of people who were traumatized (by the thefts). I mean, often, he hid in people’s closets, and they would realize that. And they would wake up the next day and realize that he had walked right by them while they were asleep, where he was in their closet while they changed clothes and went to bed,” Pederson said.

“It was unnerving, I think. You can imagine, when people talked about it, even 50 years later, they would get a tremble in their voices. They would say, ‘I was so vulnerable. I was so vulnerable. I was changing my clothes, I was in my nightgown, and he was right there.’”

Pederson worked for United Press International in Dallas while the thief was active, eventually taking a job at the Dallas Morning News. She was always interested in the unsolved crime spree, and decided it deserved its own book.

“What I discovered is not only the King of Diamonds story, but that there were several layers of crime in Dallas that didn’t get as much publicity. Besides the Mafia contingent in Dallas, there was another group called the Dixie Mafia, and there was also a group of powerful gamblers. I think more than $10 million a week was gambled in Dallas at that time,” she said.

“And interestingly enough, all three of those layers of crime, they stole jewels. One of them had stolen so many jewels, he was a member of the Dixie Mafia, that he kept them in a salt shaker in his kitchen. He had so many diamonds.”