The Republican National Convention is over – time to move from Cleveland to Philadelphia, where the Democratic National Convention (DNC) will kick off on Monday.

The DNC was held in Texas once, in Houston back in 1928. A black-and-white newsreel shows people driving around in Model Ts, a live band, and people from all over the U.S. carrying signs that said: “Alfred Smith for President.”

Debbie Harwell, managing editor for Houston History, a publication of the Center for Public History at the University of Houston, says Houston played host to the convention in part because the city was booming.

“The oil industry had taken off and was growing,” she says. “We had opened the ship channel… we had many people that were coming to the area for jobs, building new railroads, a lot of new construction in the city. It was just a place that was coming into its own.”

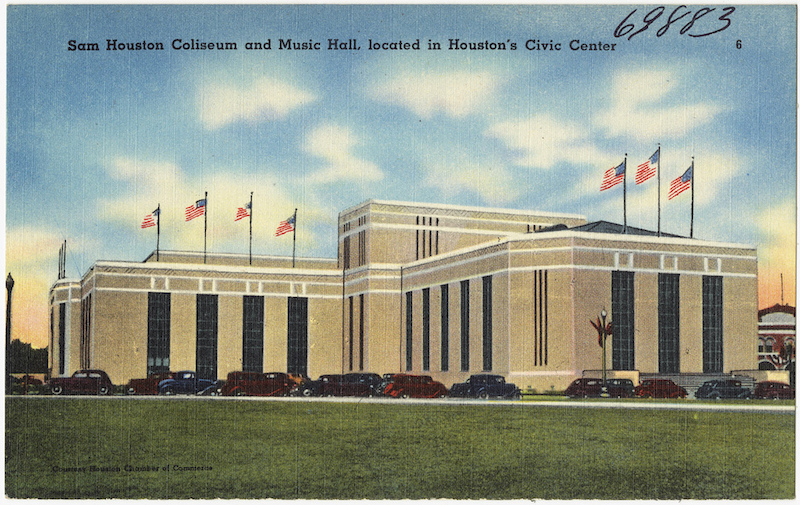

Houston’s competition at the time was other big industrial cities like Detroit and San Francisco. Entrepreneur Jesse Jones put up $200,000 of his own money – around $2.5 million today – to help build Sam Houston Hall. The convention site was built in just 64 days.

Harwell says the 1928 convention was a political turning point of sorts, for the country and the Democratic Party. It was the first time since the Civil War that a national convention had been held in the South. Tensions were high at the time, especially about Prohibition. Ultimately, Texans went for Herbert Hoover in the general election – the first time in the state’s history that voters favored a Republican.

In 1928, Al Smith, the Democratic candidate, was the country’s first Catholic to run for office. He was against Prohibition and had ties to New York’s Tammany Hall – the site of the country’s Democratic political machine. But his running mate, Joseph Robinson, was from Arkansas and a dry candidate, which helped earn him votes of dry voters.

“Prohibition was still very popular here in Texas and in the South,” she says, “especially with Protestant evangelicals.”

Another high-profile issue at the time was lynching. Republicans had an anti-lynching platform but Democrats did not. Six days before the convention, two Houston police officers shot at two black men in the city’s “Negro quarter.” The men ran and one of them, Robert Powell, shot back at the officers, killing one of them. Wounded, Powell went home, where authorities found him.

“He was arrested and taken to the hospital where he was under guard by a sheriff,” Harwell says, “but a group of seven to eight white men… pulled him from the hospital under guard and they took him to a bridge about six miles out of downtown and lynched him there. Needless to say, that did put a bad light on Houston.”

Time magazine wrote about the incident in a feature called “Houston’s Shame.” Officers arrested five suspects connected to the lynching just before the convention, Harwell says.

“Once the convention was over,” she says, “those men were released and no one was ever convicted for the crime of lynching Robert Powell.”

Despite the lynching, the convention put Houston in a positive light. It was the first convention in the South after the Civil War and Al Smith, a Northerner, didn’t get the friendliest welcome from the southern crowd.

“Al Smith got the least of the Southern vote of any Democrats since Wilson,” she says.

Smith only carried eight states, six of which were in the South: Arkansas, Louisiana, Alabama, Mississippi, Georgia and South Carolina. Other southern states that had traditionally been Democratic went Republican – including, for the first time, Texas. Ultimately, the legacy of the 1928 convention, Harwell says, was putting Houston on the national stage.

“It gave the city an opportunity to get some national attention,” she says. “…It did bring a great deal of positive attention to the community.”

Post by Hannah McBride.