This story originally appeared on Marfa Public Radio.

Historian Lonn Taylor is at a topographical map of Far West Texas, pointing to one of the most remote sections. “I’m running my finger along US 90 here on this map.” A few months ago, he was here, at the site of what’s called the Porvenir Massacre. “It’s extremely rugged, mountainous, especially on the Mexican side, lots of arroyos, extremely arid.”

Border life was chaotic back in the second decade of the 20th century. The Mexican Revolution was raging and there were skirmishes on both sides of the Rio Grande. “In the Big Bend you just had a river between you and a Civil War, ” said Glenn Justice, an historian who writes about the Big Bend region. A century ago, Pancho Villa and his supporters were leading raids on American ranches and the U.S. military was in turn pursuing bandits into Mexico. “And it caused President Woodrow Wilson to order some 200,000 national guardsmen to the border.”

Most soldiers were off fighting in World War I, but cavalry units and national guardsmen were sent in for protection. Tensions were high in December 1917, when the Brite Ranch, owned by a Marfa family, was looted. According to Taylor, the lawmen thought: “That the people at a little village on this side of the Rio Grande had participated in the Brite Ranch raid and that they had some of the loot from the store.”

So rangers, ranchers, and the U.S. military canvassed the town. Most villagers were of Mexican descent, probably a mix of U.S. and Mexican citizens. “And the army made the search and reported they had found nothing – not even any significant amount of weapons.”

The army withdrew from town. Then the rangers marched 15 men and boys out from the center of the village. Shots were fired. The rangers said they were being attacked.

“The army heard the shots and they heard the rangers leaving, and when they re-entered the village they found these 15 bodies slumped on the side of the arroyo. So that’s basically the official story.”

And it was for decades. The surviving villagers abandoned Porvenir, Texas, fleeing to Mexico. And Texas Governor William Hobby dismissed five rangers for misconduct, but that was it. By the 1980s Glenn Justice was researching it himself. “What was printed in the books didn’t agree with what the old-timers told me.”

He made this investigation his master’s thesis and eventually…a book. “As time went along, it was clear that the massacre had certainly taken place. What was not clear was who had precisely done the killing.” Said Taylor, “He was drawn back to the site of executions over and over and over again and something didn’t quite jibe.”

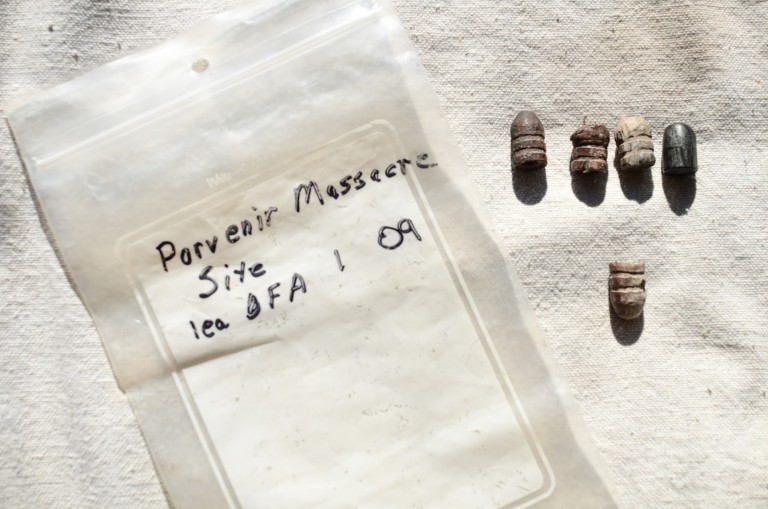

Justice had a breakthrough in 2001, when he met a survivor, Juan Flores, who was a boy when his father was killed there. “The very first day we went out there were still cartridge cases laying around on the ground, believe it or not, even after all these years.”

He now has 47 artifacts, mostly bullets and shell casings. “And the curious part of it is that they’re all US Army.” This fall, he led an archaeological dig at the site. Writer Steve Anderson was there. “It was eerie. Terrifying, sad, and strange place, especially right at the massacre site.”

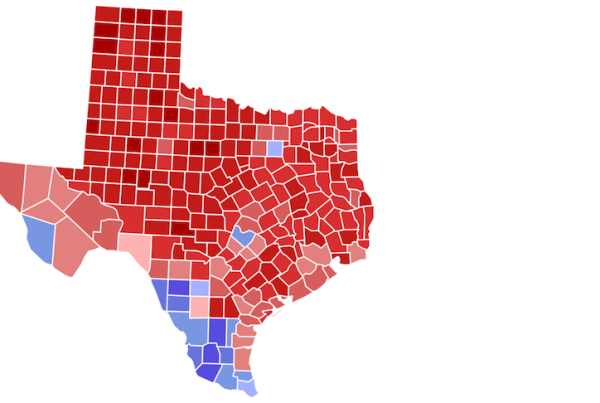

A former Texas Land Commissioner was there, too. Jerry Patterson. He’s making a documentary about the tragedy. As someone who once ran a state agency, it shouldn’t be a surprise that it’s not just history, but present-day politics that interest him. “And the parallels are phenomenal between then and now. We talk about having a national security issue now, the fear that terrorists may come across the border. Well we had a national security issue 100 years ago. Back then we had gun smuggling in to Mexico. Today we have gun smuggling in Mexico.”

And Patterson has no patience for politicians trying to exploit the border. “I guess, what was it – two or three months ago – Donald Trump made a visit to the border. Big to-do about the fact he was going down there, at great personal risk. And he says. I got back alive. What an idiot. But this perception that the border is dangerous is just bogus. But when you compare versus 100 years ago there is no danger on the Texas side of the border today.”

Justice says that a lot of hands are dirty in this incident – rangers, military, even ranchers – and 98 years is still not long enough for some of the descendants. “You know there are a lot of people who don’t want this story told.” But many here today believe there are still lessons to be learned in Porvenir and elsewhere along the border. And they’ll keep on digging.