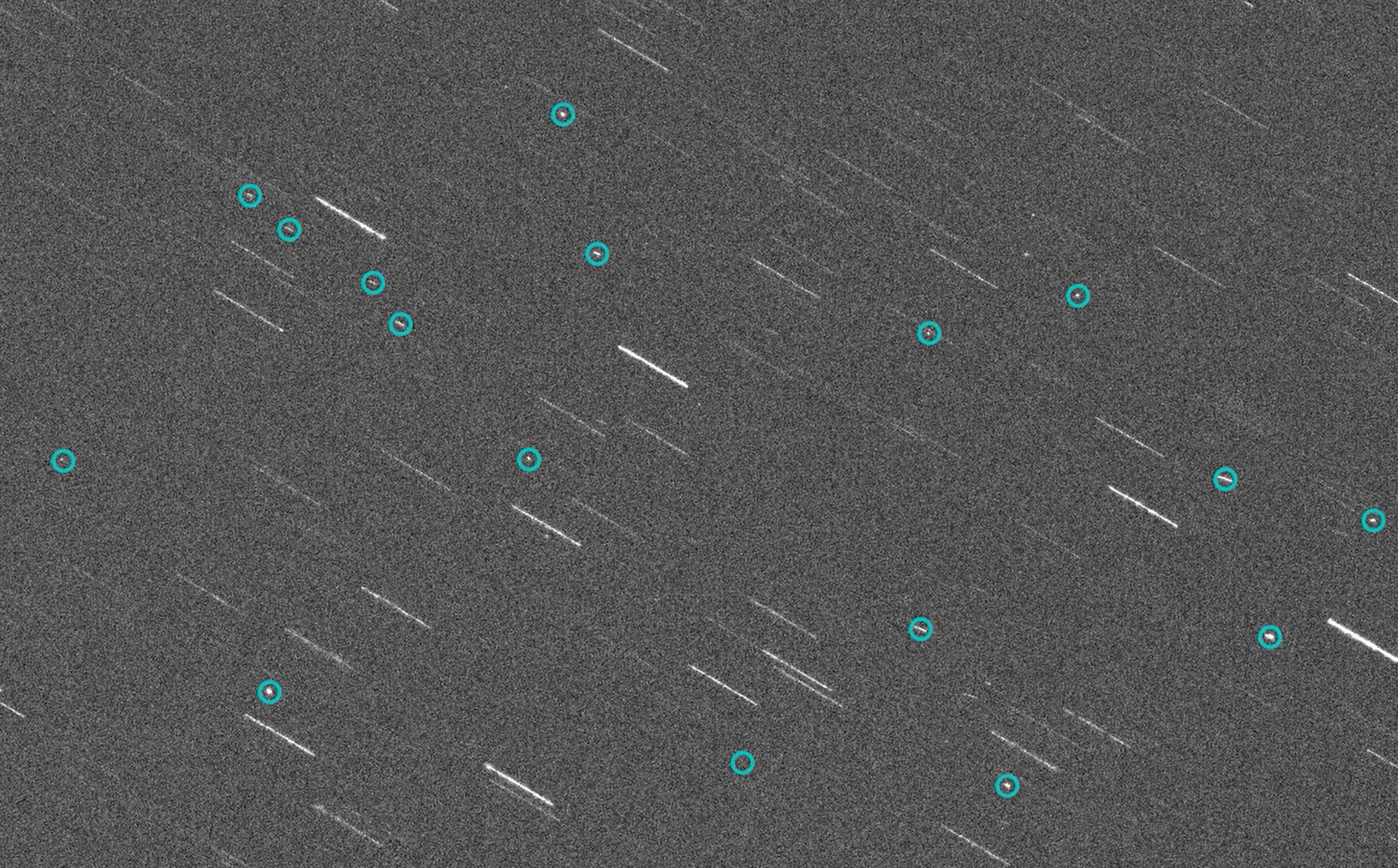

On Monday, Russia fired a missile into one of its decommissioned satellites, sending thousands of pieces of debris hurtling through space. The debris cloud could remain in low Earth orbit for years, threatening satellites and spacecraft that might cross its path.

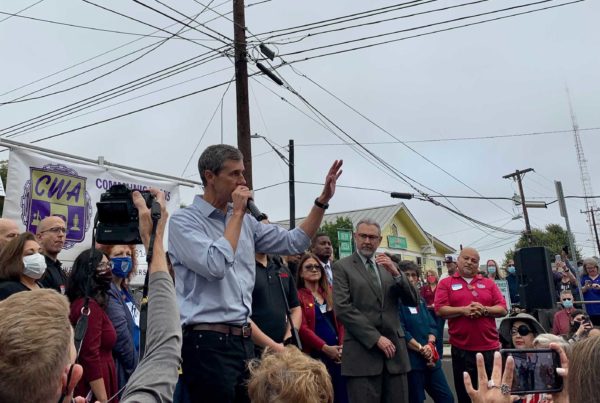

Moriba Jah is an associate professor of aerospace engineering and engineering mechanics at the University of Texas at Austin. He joined the Texas Standard to discuss the consequences of Russia’s destructive test and potential measures for mitigating space debris.

Listen to the interview above or read the transcript below.

This transcript has been edited lightly for clarity:

Texas Standard: Some of your research involves tracking space junk, like what’s left behind from this Russian military test. What are the consequences of an event like this, which has produced quite a bit more debris that’s now orbiting around the Earth?

Moriba Jah: Whenever two objects collide in space, they become many more objects and smaller pieces, most of which we can’t track. So, consider these random bullets that we have no idea when they might strike some satellite that’s providing a service we care about. That’s the risk.

For instance, if we’ve got a GPS satellite up there, it could be hit by one of these pieces of shrapnel and be rendered unusable.

Well, the altitude at which this happened doesn’t coincide with GPS. I will say that things like the Starlink satellites that SpaceX has for the global internet could be affected, and certainly, so could astronauts on board the space station.

Will most of this debris remain in orbit? Or will it eventually fall to the ground, or spin off somewhere given its trajectory?

It’s probably going to take years for most of this stuff to to reenter and burn up in the atmosphere. But, you know, a lot of things can happen in those years.

I get the sense that other countries, certainly the United States, didn’t know about Russia’s test of this anti-satellite technology. Is it unusual for a nation to take this kind of step in space unilaterally, without giving anyone the heads up?

Interestingly enough, they did put a Notice to Airmen, a so-called “NOTAM,” that went out. I actually was able to see that online. It’s one of those things where when somebody says something, you should probably believe them. But it’s certainly incredible to think that somebody could behave in such an irresponsible way in this day and age. We know better and they know better. I think that’s the biggest disappointment, to put it mildly.

As a species, we’re only putting more stuff into space. Are there particular guidelines or standards that have been developed? Or perhaps that could be put in place to help cut down on how much debris is floating free, as more outer space infrastructure comes online?

Yeah, absolutely. There’s an international committee called the IADC. They’ve put guidelines together. The United Nations Committee on Peaceful Uses of Outer Space put out 21 long term sustainability guidelines, which in and of themselves are not legally binding, but every one of the 93 countries that signed could make it into their own space law.

There’s also something called the Space Sustainability Rating that the World Economic Forum kicked off. I was part of that with MIT and the European Space Agency and BryceTech, and now the EPFL in Lausanne, Switzerland has taken that on for the next phase. That would be like a rating system that would incentivize people in basically decommissioning their objects.

So yeah, there’s lots out there that people could do, but ultimately it’s governments that have to enforce this stuff and make that transparent. That’s the thing that I’m very frustrated with. It’s all about governments getting together, agreeing to implement these things, agreeing on how to implement them and then enforcing that and making that enforcement transparent.

And right now, there’s just not the political will?

The United States wants to do this, but the U.S. alone can’t. That’s insufficient. Europe is trying to come up with its own idea of how to do this within the European Union. I just think that perfect is the enemy of good enough. These things take a while. We already have some guidelines that, if we implemented them today, would result in measurable improvements in this growth of debris. We’d be able to flatten the curve, just like flattening the curve for COVID. We’d be able to flatten the curve of the debris growth.