As high school football season moves into playoffs, another kind of competition is taking place: the Texas University Scholastic League’s marching band contests. And though most people are familiar with what’s called “corps band” – those half-time shows with catchy pop tunes and elaborate props – another marching tradition is part of the competition, too.

In pockets of the state – mostly in East Texas – some bands march in the traditional military style, with its straight lines, sharp turns and classic arrangements of John Phillip Sousa marches. They’re some of the last military-style marching bands in the country. Of the 1,077 high school bands in Texas that competed at the regional level, only 66 were military bands, according to the University Interscholastic League, or UIL – that’s just 6%.

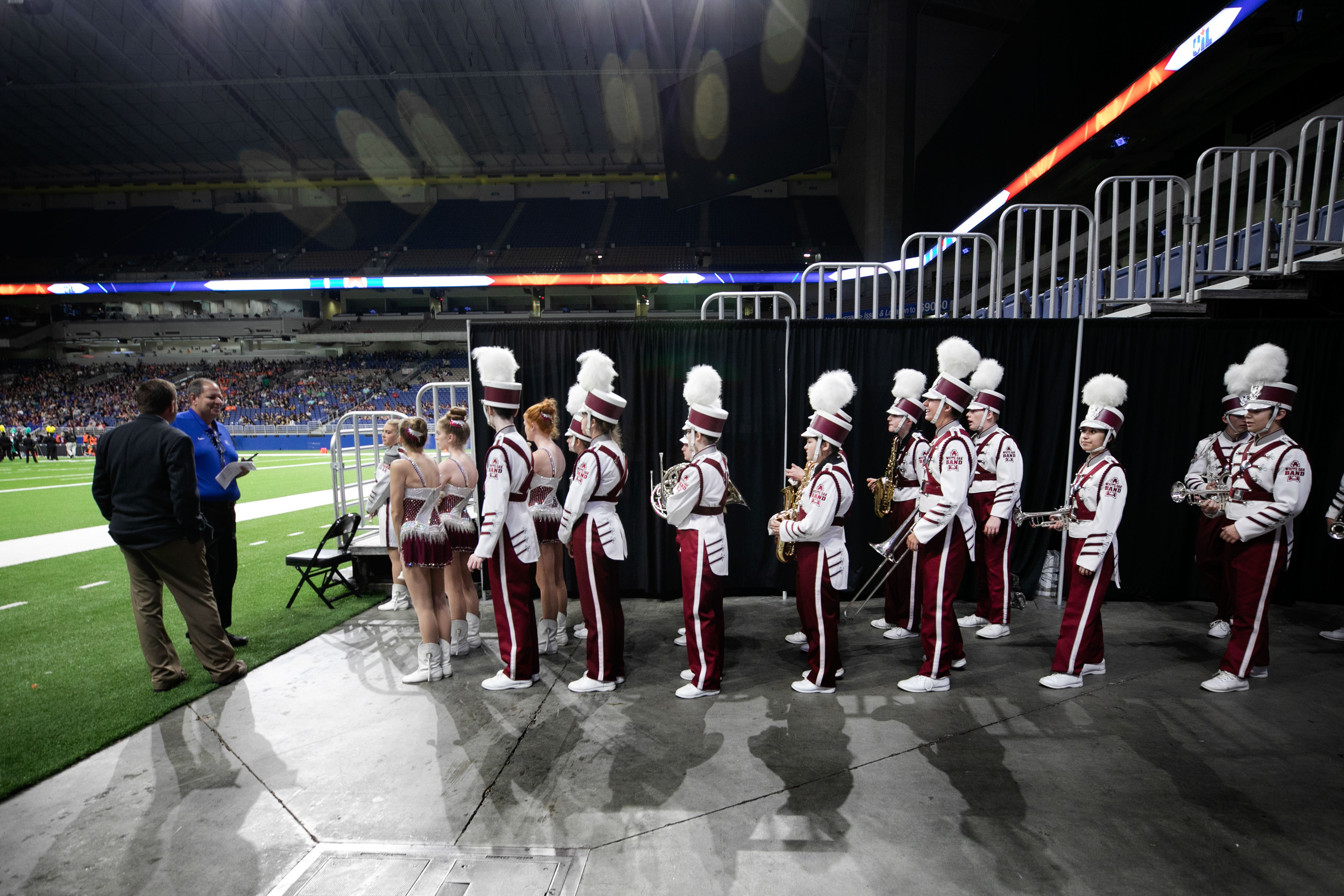

White Oaks Marching Band is one of those battling to keep a dying tradition alive, making its last stand at the Alamodome for the UIL competition. In San Antonio, 350 miles from home, the White Oak band of East Texas gets ready for the performance of a lifetime – a performance that may very well be one of the last of its kind.

Defying the odds

Jason Steele is White Oak’s band director. He knows that it’s been nearly twenty years since a band like his has won a state competition.

“[We’re] the only military marching band to qualify for the state contest,” he says.

Of Texas marching bands competing nowadays, 94% are modern corps-style bands. This type of ensemble takes a theatrical approach to marching routines that appeal to the masses: including the judges. It’s a reality that White Oak’s band tried to face. The group experimented with the format by moving away from its military roots to a fusion-style, sometimes called mili-corps. The experiment ultimately failed.

Senior Katelyn Jester is the band’s drum major. She says that the year of the experiment, the band fell short, missing out on qualifying for state.

“You could tell everyone was like, this isn’t what we’re supposed to be doing,” she says. “We’re supposed to be military band, we’re supposed to show everyone out there a military band can succeed.”

Now, she says, they’re back to doing what they do best.

“This year it’s been really grateful to see everyone’s hearts and they’re so into this march,” Jester says. “And then we’re going back to the traditional military marching and I love military marching…and its slowly going away and that’s sad.”

Next year, UIL is creating a separate event for military bands. And while they’ll technically be allowed to enter the general competition, changes to UIL’s judging criteria will make it virtually impossible for military bands to remain competitive. So, effectively this is White Oak’s last hurrah against the flashy, more popular corps bands.

The night before the competition, Steele rallies his troops at their San Antonio hotel, reminding them what they’re up against.

“Hear me on this,” he says. “You’re the only military here. You’re going into a way of thinking, with people who have a predetermined idea of what they want to hear and see.”

White Oak’s underdog story was unfolding in real time.

The plight of the piccolo

Drum beats and snare snaps fill the air the next morning as White Oak begins its last warmups at the Alamodome.

At the same time, assistant White Oak band director Randy Whatley works with piccolo players Ethan Grammer and Katelyn Willimson on their solo. It’s known that a well-executed piccolo solo can put a marching band over the top.

Because of its high register, a single piccolo can stand out over an entire band. Nailing a solo like this one is crucial. And so, for more than perhaps anyone else in the band, the pressure is on the piccolos players to be perfect.

After the warmups, the White Oak band’s 170 members line up on the sidelines waiting for their chance to perform. They take their positions: the drill begins.

In six minutes, their performance is over, leaving room for the second guessing to begin. Many of the students, like Williamson, feel as if it was far from their finest performance.

“The piccolo solo was horrible,” she says. “It was horrible. Because Ethan didn’t play and then I was out of step and then I had to drop out a couple times so it was just straight silence, cause I was trying to get back in step.”

But band director Steele’s take is a bit more generous.

“I’m pretty good, pretty good. Just nervous,” he says. “You know you never know. I think they did a good job, we had a couple errors we don’t normally have. But for the most part, the sound especially was fantastic. I think if we can crack into the finals we’ll have a better marching performance…that’s what we’re hoping for.”

White Oak needs to be in the top 10 to advance to the final round. And with their performance errors, nobody’s quite sure what to expect. They take the stands as the judges begin announcing the finalists.

They made the cut. Just barely. They’re in tenth place. But Steele sees this as an opportunity. He gathers his band for one last pep talk.

“I’ve always been happy whenever I hear finals announcements,” he says. “But I’ve never been more happy, hearing you guys shout whenever you got in the finals because it was a genuine surprise.”

The last hurrah

In tenth place, there’s nowhere to go but up as the White Oak marching band take the field one more time, for their final performance.

And it goes off without a hitch. Even that tricky piccolo solo. It was the magic performance that Steele has been waiting for all season long.

“I feel a whole lot better after this one,” he says. “First one I’m gonna be honest with you. [The] first one we had so many little marching errors I didn’t know if we were going to make it. I’m just glad we were in it.”

The band waits to see if the judges see it that way.

As place announcements begin White Oak’s members hold their breath. With each successive announcement – ninth place, seventh place, then fifth place – the band looks more and more surprised.

Then, the announcement they were waiting to hear comes over the loud speaker:

“In fourth place, please congratulate… .the White Oak High School Marching Band.”

White Oak’s final performance moves the little military band from East Texas up six whole spots. It’s the highest the band has ever finished in its five appearances at the state marching competition.

Steele is pleased with the come-from behind climb in what’s likely their final state competition, competing as outsiders against corps bands.

As the band celebrates on the field with hugs and some tears, it’s a fitting, though bittersweet end to an era.

“As far as down here in the Alamodome and competing with everyone else,” he says, “this was it. This was the last one. Fourth place finals. It was cool journey. But the journey that went from day one to right now… even the journey today from tenth place to fourth place. I wouldn’t trade for it. It’s just cool. It’s just cool.”