This story originally appeared on KUT.

In the last few years, the face of immigration from Latin America has changed: it’s become predominantly Central American.

The language spoken has changed as well. It’s still mostly Spanish speakers, but there are also more and more speakers of Mayan languages spoken in Guatemala, Belize and Southern Mexico. Millions of people speak Mayan languages across the world, but the U.S. will face a shortage of translators.

On a sunny Austin day, in a dark living room of a shelter for migrant women and children, Hilda Velazques is wrapping up a conversation with her sister.

She’s speaking Mam, a Mayan dialect spoken in Guatemala. Schools in the U.S. mostly teach a simple narrative about the Mayan empire: it flourished in Central America, then collapsed mysteriously around the ninth century. That’s true — archaeologists believe it was likely a drought or a plague, or both.

Professor Sergio Romero, who teaches Mayan languages at the University of Texas, says the descendants of Mayans live today, and so do their languages.

He teaches three of them, but there are over 30 Mayan languages and an estimated six million speakers —mostly in Guatemala, Belize and Southern Mexico.

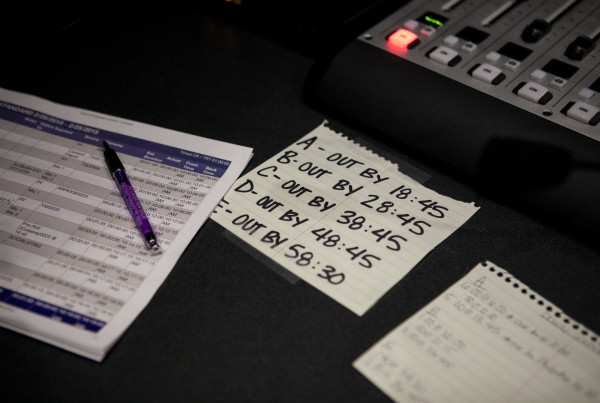

Many of them are completely different from each other. As Central America becomes the primary source for immigration, there are more Mayan speakers coming into the U.S., but a shortage of translators. Romero says when he’s not grading papers or planning lessons, he’s taking calls from detention centers and courts. He used to get called once in a while. He’s now getting about three cases a week.

“A lot of these people will be perfectly capable of purchasing beans or tortillas or beer at a store in Spanish,” Romero says. “But then engaging the police or working with a lawyer or declaring in front of a judge is not something they would be able to do.”

Because few universities offer instruction in Mayan languages, there’s a shortage of translators. Tulane offers K’iche and Kaqchikel; North Carolina University offers Yucatec Mayan.

“Until recently, the teaching wasn’t very rigorous,” Romero says. “There really wasn’t any attempt to make the students fluent.”

There might be another reason why courts are scrambling to find translators, and why more native Mayan speakers here in the U.S. aren’t stepping up to the task. Romero explains that it’s not a language immigrants are always proud to speak. It’s sometimes the language that gets left behind at the border, or even before that.

That was the case for nine-year-old Jayro Velazquez, who was taunted for using Mam. “They say that language is made up,” Velazquez says. “[They say] ‘your mother speaks an ugly language.'”

Hilda and Jayro have been in Texas for about a year, but he’s been trying to forget his native Mayan language for long before that. He decided to forget it when he started elementary school in Guatemala City because the bullying was so bad, his mom Hilda says.

“He started to pull away,” Hilda says. “He no longer spoke.”

Romero says this is not uncommon.

“The stereotypical poor person in Guatemala is a speaker of an indigenous language. The tremendous linguistic diversity of Guatemala is seen as a disadvantage,” he says. “It’s seen as one of the reasons why the country is so poor.”

Jayro talks to me in a still-awkward Spanish that is punctuated by the staccatos typical of many Mayan languages.

Hilda herself learned Spanish in the U.S., while she and her son were in a detention facility. They’d been caught at the border, and spent a year locked up. Nobody in there spoke Mam. She says she was placed with a translator whom she barely understood. She tried talking with her son, but he’d made up his mind to forget that language. So, another detainee taught her Spanish. Hilda herself hardly speaks Mam anymore, only over the phone, once in a while, with a sister.

After some prodding, Jayro tells me there’s this one phrase in Mam, an inside joke of sorts between him and his mom. It’s a very important phrase to know if you are a 9-year-old boy.

It means, “Scratch my back.”

“And I scratch his back,” Hilda says, in Spanish.