The Justice Department recently released about 6,000 inmates from federal prisons across the country. It was the largest mass release of nonviolent offenders in U.S. history, and it’s a result of a U.S. Sentencing Commission decision last year to cut sentences of drug offenders by an average of two years.

Darla Gay, a senior planning manager of the Travis County District Attorney’s office, and a member of the Travis County Reentry Roundtable, tells the Standard what that means for groups that try to help former prisoners with the transition back into society.

Gay says there 578 of the released prisoners ended up in Texas. “There were more that chose release to Texas, but most of those were deportees,” she says. Although, Gay says, they aren’t sure exactly where in the state the prisoners are going.

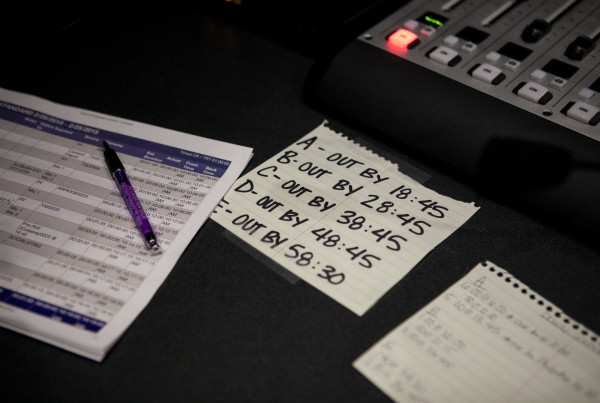

“We do know that the Bureau of Prisons operates about 18 or 20 halfway houses in Texas, and almost every one of the offenders who were released in this early release program exited through either a halfway house or home confinement,” Gay says.

She says, so far, halfway houses and other organizations that provide reentry services have kept up with the demand.

“They have not felt like they have been unprepared,” she says. “They feel like they were very prepared for the services, so I think everyone feels currently that the initial wave has been served well. It’s always going to be once they’re released into the community, and they don’t have access to those robust, on-site kind of services, that that’s where the Federal Probation Office and their reentry team are going to have to start picking up more of the load.”

Now is the time that new programs may start to pop up as service needs are made known, Gay says.

Recidivism isn’t an added worry for these organizations either, she says. “The evidence doesn’t show that that’s the case historically,” Gay says. “Yes, recidivism is always going to be a concern, but I think… each local jurisdiction is going to have to look at what their gaps are in service delivery.”

For Travis county in particular, Gay says the main worry is places for the ex-prisoners to live.

“The access to affordable housing is really strained,” she says. “People with criminal backgrounds coupled with access to affordable housing opportunities, that’s where we’re actually paying a lot more attention to. And the employment side of things.”