The United States has sent more than 800 asylum-seekers to Guatemala since late 2019. The asylum-seekers are not from Guatemala but from two Central American nations, El Salvador and Honduras. The flights bringing the asylum-seekers to Guatemala depart from Texas. Most people interviewed for this story who were on a recent flight said they will attempt to return to the U.S. But others, their spirits crushed by the ordeal of arrest, deportation and return to the very region they fled, said they will not try again.

Supporters of the Trump administration policy say such sentiments underscore the effectiveness of the plan as a deterrent to those who would seek safety in the U.S. under the terms of political asylum.

I saw people, whose night had begun in McAllen, Texas, eventually crowded around a cell phone charging station at the Casa del Migrante, one of the few migrant shelters in Guatemala City. Their faces were a mosaic of confusion and anger at having realized they were no longer inside the U.S., but, instead, in the very region they had sought to leave.

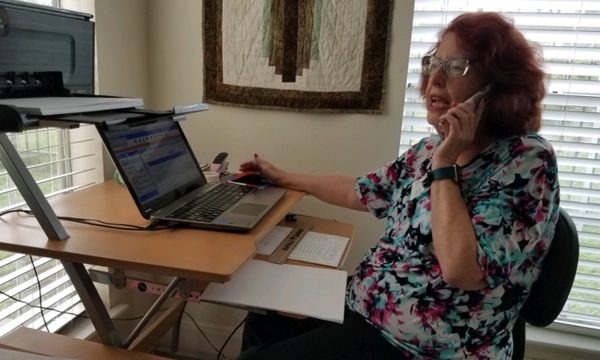

“I didn’t know what was going on,” said Natalia Medina, referring to her sudden removal from the U.S. days after she’d arrived in Texas, but before any hearing where she would have had the opportunity to detail her petition to stay. The right to an asylum hearing for those seeking safety in the U.S. is enshrined in law and under international treaty obligations.

Medina was still trying to find her bearings. She is a high school English teacher from Tegucigalpa, the capital of Honduras. Along with El Salvador and Guatemala, the three nations comprise Central America’s so-called Northern Triangle, where parallel states run by organized crime sow continual terror. Medina had hoped to leave the area to join family in the U.S. But it didn’t work out. She had been taken from the U.S. Border Patrol Central Processing Center in McAllen the night before, around midnight, and was put on a bus.

“We stayed right there, seated, sitting down, not moving, in handcuffs all the time,” she said of the hours on the bus.

Medina said approximately four to five hours later, she and others from El Salvador and Honduras were on a flight to Guatemala. She remained in handcuffs until the plane arrived in that country. Others on the flight stated emphatically that they were completely surprised to find themselves in Guatemala. As was the case with others I spoke with, Medina believed she could still apply for asylum in the U.S., from Guatemala.

“They said, ‘You’re going to continue with that in Guatemala,'” Medina recounted. “I thought that it was going to be possible to have asylum here in Guatemala, and then go back to the [United] States. But it was, like, totally a lie.”

That is a heavy allegation. I asked Medina specifically, “What exactly were you told before the flight?” She said it was clear to her after speaking, in English, to Department of Homeland Security personnel in McAllen, before the flight, that she could move forward with her U.S. asylum application once she arrived in Guatemala.

In an email, a DHS spokesperson said, “At no point are migrants told they can wait in Guatemala for U.S. asylum.”

Medina was disappointed upon hearing that.

“I guess I misunderstood, or maybe they didn’t explain it very well,” she said.

Guatemalan human rights advocate, attorney Quelvin Jiménez, says the U.S. policy is shortsighted. He said it is not reasonable to believe that people fleeing chaos in other parts of Central America would willingly stay in a country like Guatemala, with its own serious security problems.

“The United States is sending these people to Guatemala, a country that cannot protect its own citizens. This is a violent country, so it’s not a good idea to send anyone here,” Jiménez said.

Once Medina arrived in Guatemala, she was given three days to decide if she would apply to remain there. But she decided not to stay. And unlike the vast majority of asylum-seekers who plan to head back to the U.S. and try again, Medina said that dream, for her, is over.

“I would think twice to go back because I don’t want to happen the situations that happened in jail,” she said. “I don’t want to go back again.”

Medina alleges some DHS personnel in the migrant detention centers in Texas humiliated her and others as they ate or if they asked to take a shower. Medina said it was clear the officers and agents didn’t know that she speaks fluent English. She said she clearly heard agents say the migrants smelled bad and looked gross, perhaps not realizing an English speaker was listening. Medina said she kept asking herself if those guarding her had children and families of their own.

“I could perceive that they didn’t want us to be there. I have never felt depressed before, and I have been feeling depression just because I was in jail,” she said.

She told me she’d be leaving Guatemala for Honduras in a few hours.

“How they can send me to a place that is more dangerous than my country, Honduras – how is it possible?” she said.

Honduras is, statistically, only slightly more violent than Guatemala. But, for people like Medina, that’s a distinction without a difference – a meaningless number. Both nations, and the region in general, are plagued by criminal groups that target migrants and don’t hesitate to use force. The policy that sent Medina to Guatemala is being challenged in U.S. federal court. The prosecution argues that under federal law and international treaty obligations, the United States can’t force people to go to countries where they’ll be in danger.