From KUT:

Overhead, she heard the usual noise — white noise almost, for her and her neighbors. It was the clatter of cars and trucks on I-35 either blowing by in thundering herds or congealing into a seemingly unmoving hunk of metal, depending on the time of day.

Rose Walker had become a constant under I-35, like the traffic above her. And there she sat on Wednesday, sweating with all her possessions: a backpack full of shoes, a plastic tub packed with keepsakes and, most important of all, a rolling bag filled with her Medicaid paperwork, her ID and everything she’d need now that she was more or less evicted.

A “Rose in the sun,” someone joked as Walker finished up a sugar cookie, plotting her next move while the shade of I-35 narrowed under the midday sun.

Walker was one of dozens of people removed Wednesday from the homeless encampment just a few hundred feet from Austin police headquarters. The clearing of the city’s most visible camp marks a shift, as Austin begins taking a harder line on its reinstated camping ban.

But the people who lived there — most of whom are elderly and Black — say they have no place to go.

‘I haven’t even seen them’

That’s not to say they weren’t warned. Walker knew the clearing was coming; police had told the residents months before. But, as with some other high-profile camp-clearings in Austin, police assured them housing and services were on the way.

“The police said that [there] were supposed to be services coming down here to talk to us, to help us get somewhere to stay or put us in a hotel for three months, and then help us find somewhere to stay. Never seen them,” Walker said. “That’s been months ago … I haven’t even seen them.”

Walker, a native Austinite and early riser, said city crews came just after 6 a.m. Wednesday. She’d prepared, but most folks in the camp said they were told by APD the camp would be cleared Thursday; they were caught off guard.

After 8:30, police cordoned off the parking lot below the I-35 overpass with barricades and caution tape. Then crews from the Public Works Department began tossing tents and unclaimed belongings into trailers and dump trucks.

In a statement after the clearing, the city said it is “working with the people who are impacted,” but that the clearing was consistent with Austin’s reinstated camping ban.

Austin voters brought back that ban in May. Since then, APD and the city have been using what they call a phased-approach that prioritizes outreach over arrests.

Before that vote, the city decided to clear out four high-profile encampments and connect people living in them with housing through an initiative called the Housing-focused Encampment Assistance Link, or HEAL. Over the summer, police, social workers and city crews went out to the four sites, marked folks’ belongings, so they weren’t thrown away, and took people to repurposed hotels where they’d be able to sleep.

Walker said no one marked her belongings on Wednesday; no one took her to a hotel.

“[A police officer] said he didn’t care where we went. He didn’t care if we went that way or we went that way, but we had to get from up under there. That’s exactly what the police said,” she said. “They didn’t care where we went or what happened.”

The camp, which sprang up soon after the city rolled back rules around homelessness in 2019, wasn’t included in the HEAL initiative.

It’s been emblematic of Austin’s homelessness crisis — both to those who believe Austin sacrificed public safety in the name of misguided progressivism and to those who see it as a persistent reminder of the city’s failure to house its most vulnerable residents.

“You’ll see the change”

Austin Police Chief Joseph Chacon said at a press conference Wednesday that the clearing went pretty much as expected, that nobody was arrested or cited for public camping and that it was consistent with other camp clearings.

“What’s important to remember is that, throughout all of this, we have taken the approach that we want to do this in a humane way. That we wanted to make sure that wherever possible, we were providing services to people who might be experiencing homelessness — or other issues — and give them avenues to become housed,” he said. “That has continued to be the way forward for us and has been successful … but I think that if you … drive by you’ll see the change, and that is the change that we’re working to in the city.”

On Wednesday, as the shade provided by I-35 grew more and more narrow. Danielle Reichman and her partner, Chris Gould, were lying along the concrete incline under the overpass. They were exhausted.

The couple, who run a small nonprofit called Little Petal Alliance, had been helping folks at the camp and even letting residents stay in their backyard.

Reichman’s pink, green and orange technicolor mohawk darted up from the incline when asked about where these folks were going. She said the clearing was different from the HEAL clearings and there was an undeniable equity issue with how the city cleared the camp.

“Someone should be out here answering their questions, because I don’t have f- – – – – – answers. I’ve been begging them for months to house this camp. They should’ve been the first camp housed,” she said. “It’s a predominantly Black camp, and, like I said, predominantly elderly. There’s a lot of women out here. There’s queer and trans folks at this camp. It’s just disgusting what the city did today. What they’ve been doing for weeks is disgusting.”

Reichman said she saw the same confusion in June when police cleared out an encampment that sprang up outside City Hall after the ban was reinstated. In the aftermath of the clearing on Wednesday, she and Gould were working to get temporary housing for 14 folks staying at the I-35 camp.

“Slipping through the cracks”

Advocates say this camp — and the issues related to housing and services — is endemic of a larger equity issue within Austin’s response to homelessness.

The people in camps cleared out under the HEAL initiative were connected with shelter if they wanted. They were given coordinated assessments, which is the first step to getting on a list for housing.

Reichman found many folks at the camp under I-35 hadn’t been provided those assessments. So, she invited another unofficial service provider, the Sunrise Community Church, to get people set up with them Tuesday night, as the rain came down in sheets.

Sunrise found that many of the 50 people assessed hadn’t been contacted by anyone to get housing or services — in an area of town where the bulk of service providers are located. Most said it had been four years since they’d been contacted by a case manager or had someone reach out about getting into housing.

Nearly all of the folks were Black.

Black Austinites make up a disproportionate share of the city’s homeless population. About 7% of the city’s population is Black, but nearly 40% of people living outdoors are Black, according to the Ending Community Homelessness Coalition’s last census of Austin’s homeless population. It’s a glaring inequity in a city where growth is pushing Black communities to the margins or forcing them out altogether.

In an email Wednesday to the city’s Homeless Strategy Office obtained by KUT, Sunrise called the service gap “uncanny” but suggested it was a result of the Austin Resource Center for the Homeless’ 2019 transition from day-to-day services in favor of a client-based approach that focused more on people within the city shelter.

“[This] should challenge us to think about how we can actually provide walkup & outreach assessment (along with mental health care) to these vulnerable people and how we think about equity for these heavily-African American, heavily-elderly populations that are going unserved as it relates to our housing system,” the email read. “They’re clearly slipping through the cracks.”

As of Friday, Sunrise had not yet received a response, but suggested the city push providers to focus more on providing consistent walk-up services at the ARCH and other organizations downtown.

Residents say they were not offered temporary housing or services when the camp was cleared.

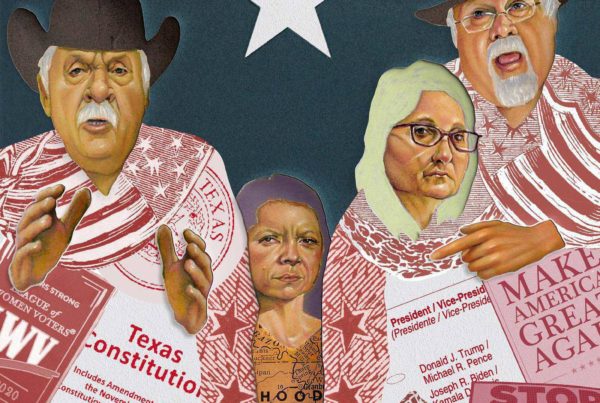

Michael Minasi

In an emailed statement, the city said shelter capacity is limited and it’s “not in the position to offer immediate housing or shelter to everyone who is subject to enforcement” of the camping ban.

It noted that neither Prop B nor the new state law against public encampments provided any funding for housing or shelter.

“Homelessness is a community-wide challenge right now and we welcome our partners’ support in addressing it,” the statement said.

As for Walker, she said she’s weathered tough transitions before. She’s struggled with drugs and was incarcerated until last year. She’s had a hard time adjusting to life outside prison and adjusting to COVID.

But she said she’s had a harder time adjusting to the way Austin treats homeless folks.

“This is my home. This is my home. I just didn’t know all this was going on … how they do the homeless people. That’s what I didn’t get — and I can’t get — because they do the homeless people real bad here. And it used to not be like that. It’s like everything just changed,” she said. “My prayer is to get me a roof over my head. That’s what I want. Not to be staying outside.”

For now, Walker has a roof over her head. She’s staying in a motel room for at least a week paid for by Reichman’s group. After that, the road isn’t exactly clear.

Got a tip? Email Andrew Weber at aweber@kut.org. Follow him on Twitter @England_Weber.