On Oct. 9, 2012, under the soft light of the Southern California sun, President Barack Obama spoke to a crowd of thousands.

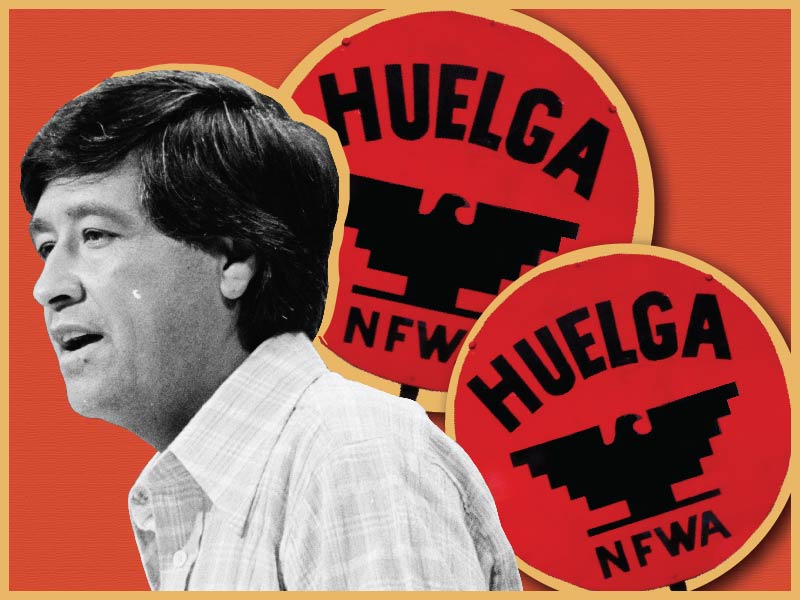

He had arrived in Keene, Calif., earlier that day to dedicate the César E. Chávez National Monument, located at the former headquarters of the United Farm Workers, nicknamed La Paz – “the peace.”

The monument spans only two acres but is home to both a museum and the gravesite of Chávez and his wife, Helen. It’s one of countless monuments, schools, parks and streets either named or renamed to solidify his place in American history.

Obama’s speech focused on things everybody knows about Chávez: He was an organizer, he fought tirelessly for farmworkers, and he refused to compromise on his principles.