It was a time of enormous division in the U.S. For many who supported the Vietnam War. Potesters and conscientious objectors were often viewed as unpatriotic – unwilling to serve their country.

But that dividing line wasn’t quite as clear as has been depicted through the years.

It was conscientious objectors who straddled that line. Compelled by conscience to oppose the war, many nonetheless agreed to put on the uniform and serve in the field – without weapons and in protest.

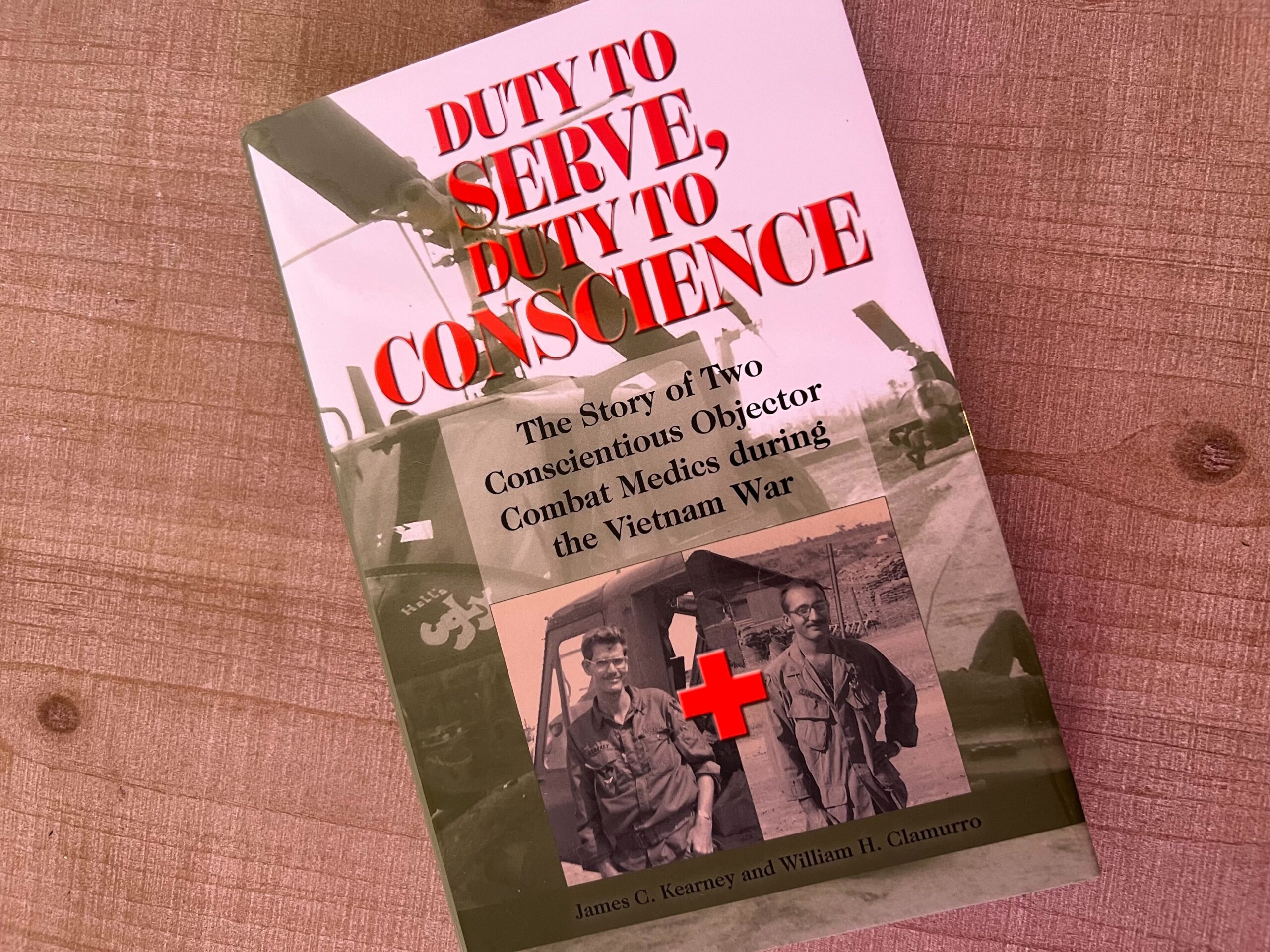

Such stories are seldom told, which is one reason the new book “Duty To Serve, Duty To Conscience: The Story Of Two Conscientious Objector Combat Medics During The Vietnam War” is such a compelling and important read. The co-authors are James Kearney, a professor in the college of liberal arts at the University of Texas at Austin, and William Clamurro, a professor emeritus of Spanish at Emporia State University in Kansas.

Kearney spoke with Texas Standard on what it was like to be a conscientious objector in the middle of a war zone. Listen to the interview above or read the transcript below.

This transcript has been edited lightly for clarity:

Texas Standard: Take us back. What did it mean to be a conscientious objector?

James Kearney: The one thing that’s unique about Vietnam was the draft. This is the thing that set it apart from wars that we’ve had since then.

As undergraduates here at the university, we had a deferment, but that deferment expired when we graduated and we were reclassified 1-A eligible for the draft. What to do? And this is a decision that thousands, if not millions of my, you know, contemporaries faced. And it was a defining characteristic of the war.

The Selective Service Act of 1940, which was operated through the Vietnam War, gave two classifications – those willing to to serve and put on a uniform, but without weapons training, without weapons. All of these people were trained as combat medics. And then the other, the larger class, were those not willing to put on a uniform at all – the 1-0s. And they did alternative service.

But whether the one or the other, it had to be based on religious reasons. And not only that, but you had to be opposed to all wars, not just the war at hand.

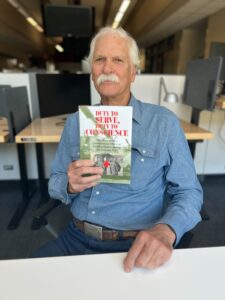

Co-author James Kearney, who was a conscientious objector combat medic during the Vietnam War. Kristen Cabrera / Texas Standard

So how did you approach this when your number came up?

Well, I did not apply on religious reasons. So how did that happen?

Several Supreme Court decisions opened the gates to people who did not come from traditional pacifist religious backgrounds – like the Amish or the Mennonites or the Quakers or the Seventh Day Adventists. You can have your own ethical journey, which could be religious or more just ethical.

And so we began to have a new breed of conscientious objectors in Vietnam that were more political than religious. And I fall into that category, as I did my friend Clamurro.

Tell me more about meeting Clamurro. I guess you met during training, right?

We met at the most unorthodox unit in the U.S. Army – Echo Four at Fort Sam Houston. This is very much a Texas story, by the way, because all 1-A-0s – that was our classification – were trained at Fort Sam Houston in a particular unit called Echo Four. And we happened by the luck of the draw to be in the same basic training class together. And naturally, we gravitated together. And Bill and I, our friendship began in basic training.

How were you treated when you were in training and later when you were in the field?

Well, that’s a very good question. Our particular classification allowed us to reconcile our consciousness with our sense of duty. We were not trying to avoid anything.

The Army was very comfortable with this situation because it began and existed throughout World War II. You remember the movie “Hacksaw Ridge”? Desmond Doss? He was a 1-A-0, just like me. One of the most decorated soldiers in the Pacific Theater in World War II.

The Army was comfortable with us. We made a bargain with the Army. We would be good soldiers. We would be good medics. And by and large, the Army lived up to their side of the bargain, as well. And we were all tested now and then.

But by and large, we were treated well, even with respect. And even then we found that sometimes in the field, the field commanders requested us, because they knew that we would do a good job.

I’m curious about why you and your colleague, William Clamurro, decided to write this now, and in particular, the way that you structure this as a kind of dual memoir.

This is common experience. At a certain point, people who actually experience combat – and we were both in the thick of it, by the way, in Vietnam. We were on A-Team, so to speak.

But we tried to put the war behind us after we were dismissed. But at a certain point in your lives, you feel like you have to come to terms with the experience because it’s the most intense experience of your life. And for us, when we looked at each other and said, “you know, I’m beginning to think about the war and trying to come to terms.” And we said, “Well, if we do something, we have to do it together.” Because our friendship was forged in Vietnam – has lasted 50 years and we’ve seen each other at least once. We have to do it together.

Along the way, of course, you and William were separated after training, but you were injured. Could you tell us about your reuniting with Clamurro?

Yeah, we both got reassigned a couple of times and I won’t go into the details. It had to do with the Nixon/Kissinger plan of standing down and Vietnamization.

But anyway, I went from the 1st Infantry Division to the 25th, and then we both got reassigned to the 1st aircrew and we found ourselves for the last five months of our tours of duty in the same unit. But I was a flight medic for medevac and he manned the aid station at Phúc Yên.

Well, I only had a week left in-country on my tour of duty when I got involved in a very hot hoist” we called it – a combat situation. And I was severely wounded. And when that helicopter managed to limp in to the aid station, none other than Bill was on duty and gave me first aid, which consisted of, in the first instance, of a cold beer. So that forced, if nothing else, a lifelong friendship.

This is hard to sort of articulate, but I’m giving my best shot. On the one hand, you oppose the war, and yet once you’re there, well, you know about the collegiality that is such a part of the military experience and also, of course, how some of the values that soldiers had, you know, wanting promotions and such.. There’s a certain prestige that comes along with certain assignments. You’re flying into a war zone to save people. Did you feel personally torn or were you comfortable with what you were doing and who you were?

Well, the medevac, 1st Air Cav, was all volunteer. In other words, I mean, the pilots were the best of the best. The medics had to be proven and seasoned. They didn’t take green medics. The flight crews, the flight chiefs… everybody volunteered for this mission.

Our mantra was “so that others may live.” That’s a saying – or ethic, whatever you want to call it – that was perfectly consistent with my beliefs. And everybody, whether they were COs or not, in my medevac unit believed in this. We were here to save lives, not take them.

And it’s hard to explain to people, but I loved it. I loved the camaraderie. I loved the mission. And I voluntarily extended my tours of duty because I felt like I was doing something worthwhile. And people find that incomprehensible. “How could you have done that?” Well I gambled and I lost because it was an extremely dangerous job – we had a 20% per year casualty rate in medevac.

You ever have folks come up to you later in life say “thank you for your service”?

Yeah, I hear it all the time and I appreciate it, you know?

But here’s the point. You have to realize, you know, Bill and I don’t claim any high moral ground. We made a compromise. And those men, those COs who refused to even put on a uniform, they often say, “well, you are helping the war effort.” And I say, “yes, I guess I was. But I’m not a saint. I felt a duty to serve and I felt a duty to conscience. And this particular classification allowed me to live with myself.”

I wonder, you know, often history is looked at in light of the present and certainly what lessons might be extracted. And you think about how divided the country was then and how divided in other ways we are now. And I’m wondering if that in any way was in the back of your mind as you and Bill were writing this book?

Oh, absolutely.

I mean, people ask me, “were there any redeeming things about Vietnam?” And I would say, “well, there would have been if we learned the lessons of Vietnam, but apparently we didn’t.” And that’s very distressing.

But there was another purpose to our book that sort of ties into what you’re asking. It’s about the draft. It’s about debt. What is our debt to society? I mean, should there be a public service? Should people be compelled to serve their country and if not in the military, in some other? And we wanted to be part of this conversation because there are certain problems with a volunteer army, you know, and having a public that is disconnected from the foreign policy because there’s no skin in the game.

I mean, when I was a student here at the University of Texas in the heyday of the sixties, I experienced all that. We were involved because, you know, it’s a cliche, but we had skin in the game because of the draft. When the draft ended in 1973, there were some things that were lost, and we call that in our particular situation, “the conscience” that was lost. Because we had a consciousness opposed to war embedded in the very midst of war. And that’s something we think is unique in history. It never happened before or after.

Jim, where do you come down personally on this issue of compelled service to your country?

I’ve changed my mind, you see, because we hated, loved and despised the draft at the time. But now I’m beginning to have second thoughts about that. I’m beginning to think that we do have a debt.

And you know that the draft was not all bad. But if we did reintroduce the draft, we have to think very hard about what provisions should be made for conscientious objectors. And these are not easy questions. There are no easy answers to these. And to what extent should women – should they also be drafted or should they be compelled to offer some sort of alternative service? You see what I’m saying? Something like that.

So we wanted to be part of that discussion. We wanted to say, “hey, wait a minute there.” I mean, an all-volunteer army. OK. Well, but there are also problems with that.