She’s been called the “mother of American modernism” – and chances are you’ve seen her masterful paintings of life-sized flowers, New York skyscrapers and desert landscapes. But photography is an important aspect of Georgia O’Keeffe’s artistic career that’s not as well known.

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston is hoping to change that with what they call the first major exhibit of the artist’s photographs. It’s called “Georgia O’Keeffe, Photographer.”

Lisa Volpe is associate curator of Photography at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.

Listen to the interview above or read the transcript below to learn more about the exhibit, which runs through January 17 of next year at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.

This transcript has been edited lightly for clarity:

Texas Standard: Georgia O’Keeffe started shooting photographs as a young woman, but really picked up steam later, inspired by some of her photographer friends. Where was she in her artistic career, and how did photography fit into that?

Lisa Volpe: She really began thinking about photography as a possible artistic practice for herself in 1955. So, she’s 68 years old. Most of the paintings that we know of have already been produced. She’s finished a series of her epic Selita doors, but she’s an artist at heart and she looks out in her home in Abiquiu, New Mexico, and at that beautiful New Mexico landscape, and she just doesn’t feel like she’s done with it.

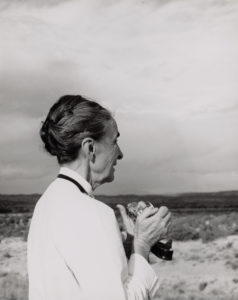

And so in 1955, a friend and photographer came to visit. His name is Todd Webb, and it’s on Webb’s visit that she picks up the camera again. Webb comes back several summers in a row. Todd writes letters home to his wife, Lucille. He said, “I’m teaching Georgia to photograph. She has some sense of it. I think she’ll do well,” which I think is the understatement of the century. And it’s from that time on that we have her body of photographs.

You spent more than three years researching and looking at thousands of images and created what you called an epic timeline. Can you tell us more about some of the photographs in the exhibit? How did you go about deciphering – because she did have all these photographer friends – that this really was her work?

That was the really tough part of the project. It began because Cody Hartley, who is the director of the O’Keeffe Museum in Santa Fe, New Mexico, casually said to me one day “We have all of these photographs. We don’t know who they are by, but we think some of them are by O’Keeffe.” And I was so intrigued. I read all of her letters. I plotted where she was geographically in the world, what she was thinking about, the appearance and deaths of her dogs, the remudding of her Adobe home, just so that I could start to say, “Yes, she’s at Glen Canyon at this moment. So, which one of these photographs of Glen Canyon are likely hers?” What shows her vision? What isn’t the vision of her photographer friends around her? I looked at thousands of images to arrive at the 409 that we can now confidently attribute to O’Keeffe.

Tell some more about some of those photographs. Do you have a favorite?

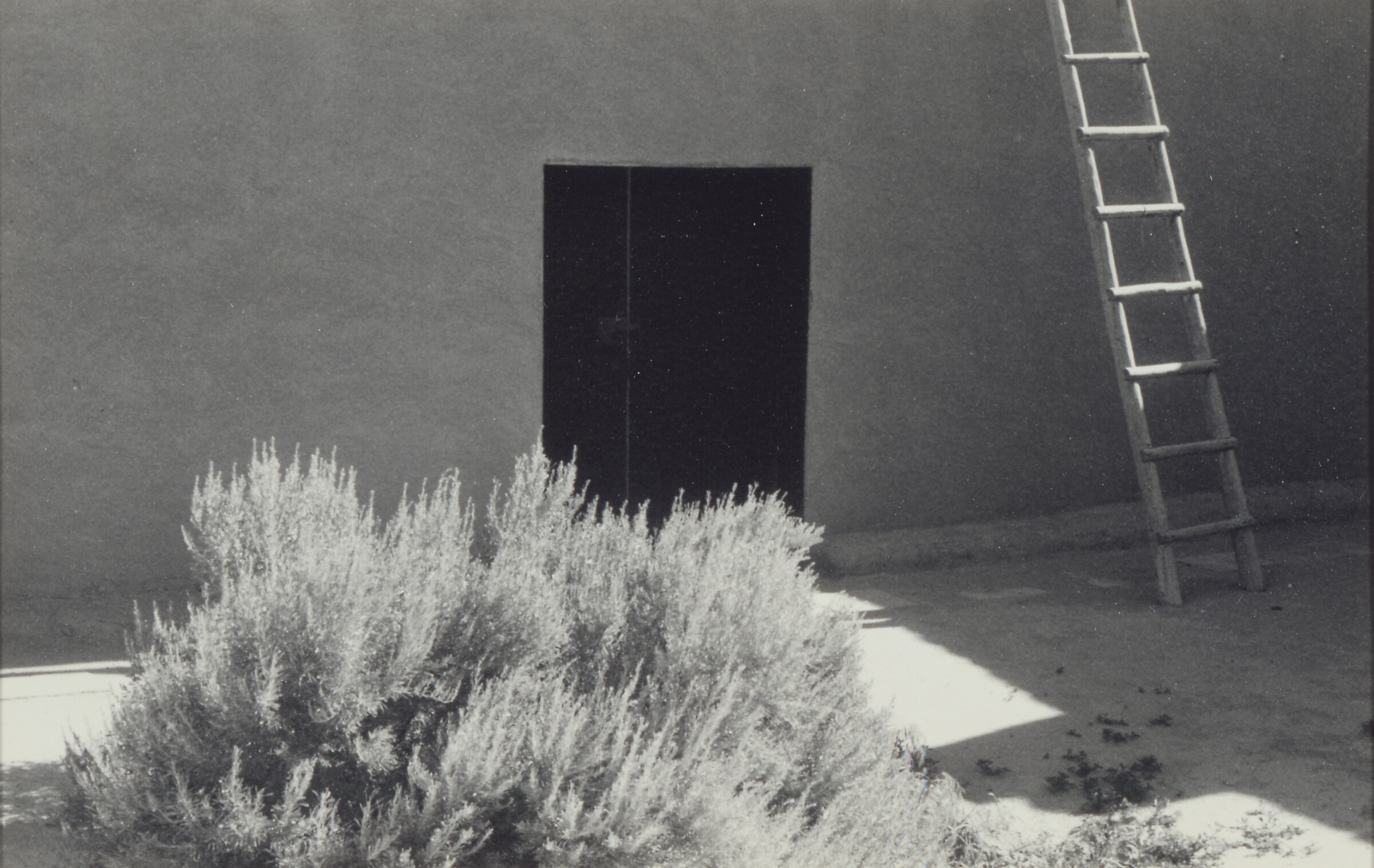

I do. O’Keeffe had a very clear way of photographing that was different than any of her photographer friends. It’s something we call reframing. She was taking sequential images, and she would just change something slightly with each capture. She wouldn’t take a photo of a door and then suddenly point her camera at a tree. She would photograph the door straight on. Take two steps to the left. Photograph it there, raise her camera, photograph it again. Take two steps back. Photograph it again. She was just changing the shapes of how things were organized within the frame.

Georgia O’Keeffe, In the Patio VIII, 1950, oil on canvas, Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe, gift of the Burnett Foundation and the Georgia O’Keeffe Foundation. © Georgia O’Keeffe Museum

There are two photos- one done horizontally, one done vertically- of the wall outside her studio. It’s winter. You can see snow on the ground and this beautiful line of bright white snow on top of the wall. And there’s a kiva ladder leaning on the wall outside of her studio door and the shadow of the kiva ladder points your eye exactly to this pile of bones that’s sitting outside her studio. I love thinking about how she saw it perhaps and ran for her camera because the shadow was going to move. Or maybe she saw it and had to wait till the next day for that shadow to be in that perfect position again. It’s just so O’Keeffe.

O’Keeffe was born in Wisconsin, but she spent much of her life elsewhere, most notably in New Mexico, at the end of her life. But she also spent some time in Texas. Can you tell us more about her time in Texas and what she created while she was here?

Texas is a really important part of her story. She came to Canyon, Texas, in 1916 to begin teaching. She was the head of the art department at West Texas State Normal College. Her sister Claudia joined her in October of that year to go to school while Georgia was teaching. And it’s Claudia that brings a camera with her to Texas. She’s trading the camera back and forth with her sister. They’re posing on these wide Texas plains or in front of these board buildings.

And Texas is a great starting point for O’Keeffe for other things. She creates these beautiful abstract charcoal drawings that she calls specials. Those are what catch the eye of Alfred Stieglitz, who eventually exhibits them in his gallery. They start corresponding back and forth from Texas to New York, and start trading photographs back and forth. And of course, they’d be married in 1924.

So artistically, professionally and personally developed that relationship.

Todd Webb, Georgia O’Keeffe with Camera, 1959, printed later, inkjet print, Todd Webb Archive. © Todd Webb Archive, Portland, Maine, USA

Absolutely. And she loved the Texas light. It’s really in Texas that she starts to think of light as form. There are these fantastic watercolors called Light Coming on the Plains, where she’s depicting the light as these arced forms of color.

What are you hoping to add or achieve when it comes to O’Keeffe’s legacy with this exhibit?

I’m hoping that we listen to O’Keeffe herself. One of my concerns was, would O’Keeffe have wanted these photographs to be seen? But there are so many hints that she did. She left us a trail of breadcrumbs to find them. In her 1976 Viking press book, next to the painting “Road Past the View,” she writes about using photography. She says, “I picked up my camera. I took two or three snaps of the road.” She’s telling us photography was part of her story. I hope that I’m just bringing it to light for her.

Editor’s Note: An earlier version of this story misidentified O’Keeffe’s place of residence in New Mexico. She lived for many years in Abiquiu, New Mexico.