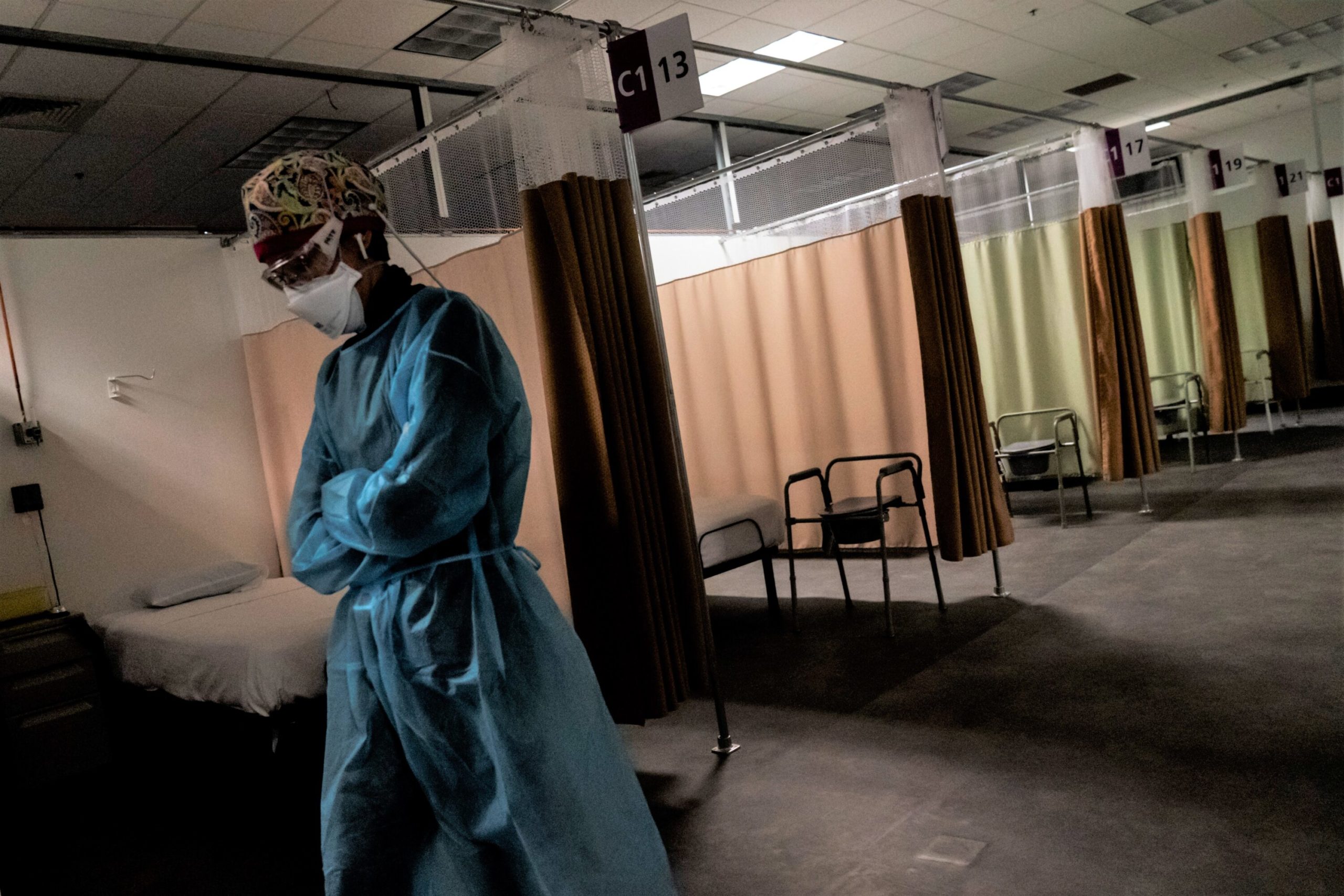

At the very beginning of the pandemic, nurse manager Avery Taylor volunteered for the COVID-19 unit at Houston Methodist Hospital. She didn’t quite know what she was signing up for, but she was ready to help.

“It was chaotic and frantic, but there was a lot of energy from health care providers,” Taylor said. “This was our time to really step in and take care of our community.”

Many Houston nurses took on dangerous assignments without proper protective equipment and effective treatments for patients. Some even traveled straight to the COVID epicenter in New York, where people banged pots and pans everyday in gratitude to health care workers risking their lives.

But eventually that energy started to fade. COVID settled in to a cyclical pattern of surges, which weighed on both nurses on the front lines and a public fatigued by public health restrictions.

Taylor thought she would be in the COVID unit for a month. Two years later, she’s still there. In late July, as the delta variant started filling hospital beds, she was exhausted and running on fumes.

She went on to witness an unprecedented number of people dying, all while vaccines were becoming widely available. It weighed on her mental health. The suffering and death felt senseless.

Lots of nurses felt this way, including Kaitlyn Chahar, an ICU nurse from Houston who spent most of her career working in Colorado. Patients have cursed her out or thrown urine at her. She has slowly noticed a shift from gratitude to indignation.

“It turned into people who don’t believe in COVID,” Chahar said. “They don’t want to get vaccinated, they don’t understand why their loved ones are dying, they think that it’s fake.”

All of this burnout has worsened an already drastic nursing shortage during a time when nurses are most needed. Even before the pandemic, Texas’ was projected to be short 60,000 nurses by the end of the decade, according to projections from the Texas Center for Workforce Studies. And people in the industry say it’s likely to get worse.

Vivian Health, a hiring platform for health care workers, saw demand for travel nurses surge in Texas this month, likely because full-time staff have left. The number of jobs went up by almost 50% in March, compared to February.

Those assignments typically last two to four months. Assignments may take nurses out of state or to another hospital in the region, especially as Houston faced its worst surges of infections.

Chahar has been a travel nurse since December 2020. Despite feeling burnt out, pay has incentivized her to stick it out a little longer. One assignment paid four times the wages she earned as a full-time nurse, she said. As a result, she’s been able to pay off credit card debt and support her husband’s dream of becoming a professional golfer.

Full-time jobs pay $1,500 a week on average in Houston. Travel nurses make about $2,900 a week on average, according to Vivian Health.

While pay is one factor for leaving, another concern is the conditions nurses have work through: grueling hours, understaffing and angry — sometimes violent — patients.

Throughout the pandemic, Chahar said she experienced all of it firsthand — especially during the peaks of COVID waves.

“I was on my feet all day,” Chahar said. “It was exhausting. I wouldn’t eat. I wouldn’t be able to pee. I wasn’t drinking water because you’re just constantly doing things in your patients room to make sure that they don’t die, and a lot of them still died.”

Texas Nurses Association President Cindy Zolnierek said patient deaths have taken an emotional toll during a pandemic that’s killed more than 80,000 Texans — most of whom were unvaccinated.

“The stress of seeing so many patients die was unimaginable for nurses,” Zolnierek said. “They were seeing multiple numbers of people die every shift, every day. And then in their minds is, ‘ did this person need to die?’”

The shortage has been a wake-up call for a lot of hospitals, said Maja Djukic, associate professor at UTHealth’s School of Nursing.

“They are, for the first time, really trying to listen to nurses’ needs,” said Djukic, who studies the nursing workforce in Houston.

The result is that nurses now have a lot more leverage to advocate for things like daycare, green spaces and flexible work schedules.

“Environment, turnover, stress and burnout, that’s nothing new,” Djukic said. “But I think the response to those issues by health care systems is different this time around.”

Houston Methodist, for example, opened up an emotional wellness clinic for employees and their children last year. Co-pays are also free of charge for nurses seeking care from in-network mental health providers.

Avery Taylor encourages her nurses to set boundaries as part of creating a healthy work environment. She is making sure that her nurses all take a summer vacation this year.

“You can’t pour from an empty cup, right?” Taylor said. “I am still incredibly proud to be a nurse, but I don’t feel like I have to be a nurse at the sacrifice of myself. I still need to take care of myself.”

But not all nurses are experiencing this paradigm shift.

Vivian Health conducted a recent survey of 285 Texas health care workers. More than 36% said they’re considering leaving their profession within the next two years.

Kaitlyn Chahar said it’s not an easy decision, but her days in nursing are numbered — the job no longer fulfills her.

“I’m going through a quarter-life crisis. I always wanted to be a nurse and now I have no idea what I want to do,” Chahar said. “It’s very scary, it brings me a lot of anxiety. But after seeing so much death, I only want to be happy and do things that I truly love and enjoy doing.”