A Russian paramilitary force took over a southern city and marched toward Moscow this weekend before abruptly standing down, leaving many to question the strength of President Vladimir Putin’s regime.

Yevgeny Prigozhin is the owner of the Kremlin-allied Wagner Group, a private army of inmate recruits and other mercenaries that has fought some of the deadliest battles in Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. On Friday, Prigozhin escalated months of criticism of the war, calling for an armed uprising to oust the defense minister. The Wagner Group took over the military headquarters in the city of Rostov-on-Don, then marched toward Moscow.

The uprising did not last long. Prigozhin stood down the following day, and as part of the deal to defuse the crisis, he agreed to move to Belarus.

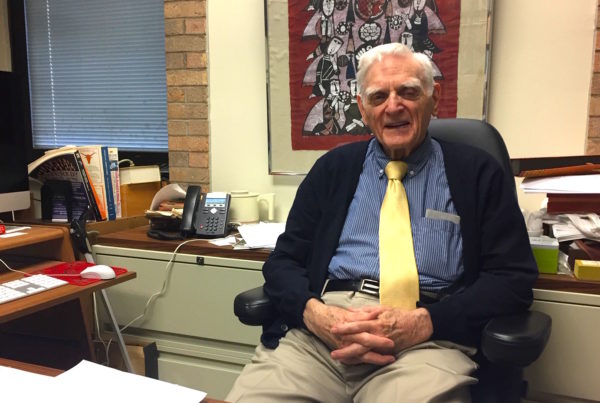

Jeremi Suri, the Mack Brown Distinguished Chair for Leadership in Global Affairs at the Lyndon B. Johnson School of Public Affairs at UT Austin, said this weekend’s events raise serious questions about Putin’s hold on power.

Prigozhin and the Wagner Group have historically been empowered by Putin to act in favor of the Kremlin outside the normal channels of government control in Russia, Suri said, and Prigozhin wanted this independence to extend to the war in Ukraine.

“One of the arguments he made is that the military leaders of Russia, particularly Defense Minister [Sergei] Shoigu, were messing up the war, and [Prigozhin] didn’t like the fact that they were restricting and trying to boss around his soldiers. He believed his soldiers should operate independent of Russian government control,” Suri said. “He has argued not just for more autonomy in Ukraine, but that the Wagner Group should have more autonomy in Russia and elsewhere. He doesn’t want them to be under any government authority at all. So he was basically fighting for the independence of his militia.”

Suri said that while there is little evidence that Russian soldiers joined the march, the Russian military did little to stop it.

“Russian traditional army soldiers – the ones who were ordered in some ways by Putin to stop this mutiny of Prigozhin’s forces; the regular Russian forces – did very little,” Suri said. “In Rostov, the city that Prigozhin captured, and along the highway to Moscow, there’s very little evidence that the traditional Russian soldiers tried to stop the militia. And what that has led many observers to think is that there’s not a lot of support for Vladimir Putin in the Russian military.”

Suri said Putin has insulated himself against coup attempts by creating rivalry in the ranks below him so military and paramilitary leaders focus on currying favor rather than overthrowing the existing power structure.

“That is what Putin has been doing by playing the Wagner Group off of the regular Russian military. There’s another group of militia under Akhmad Kadyrov, who’s a Chechen fighter, and that seems to make people think of Putin as a dictator as somewhat coup-proof,” he said. “But there’s always a challenge, a hazard that one of those groups could get too strong and that that other power center, one of the groups that you create is a rival of the others, could actually achieve a position where it could dominate the others and take control.”

Suri said Russia might have reached the precipice of that situation this weekend.

“What we saw with Prigozhin’s forces is that they got pretty close to Moscow, about 150 miles away, with very little resistance. And we honestly don’t know what would have happened if they had gone into Moscow. Maybe Russian forces would have resisted, maybe not. It certainly would have gotten very ugly,” Suri said. “I don’t think Vladimir Putin could be certain what would happen in that situation, which is why I think he made this deal with Prigozhin [to send him to Belarus] to prevent that fighting from happening.”

Suri said this could be the beginning of the end for Putin, though it is hard to predict what will happen next.

“What we do see are two things: Putin does not have the ironclad authority and does not have unimpeachable support within Russia,” Suri said. “The second thing – and this is really important – other figures like the president of Belarus, [Aleksandr] Lukashenko, these figures are important as well. Lukashenko negotiated the deal for Putin, and Putin’s reliant and dependent on other figures. So he looks weaker and he looks less independent than we thought before this incident.”