Most mornings, Rice University Geology Professor Cin-Ty Lee can be found strolling through campus with a pair of binoculars in hand, his eyes on the sky.

Lee has been birdwatching since he was a kid, but his hobby was sidelined during pandemic stay-at-home orders.

“We couldn’t go running around looking for birds, so we thought what are we going to do?” he said.

Lee had heard about people putting up microphones to record migratory bird calls at night, so he and a friend decided to give it a try. At first, it was incredibly boring.

“For a couple of weeks, there was nothing. I thought this is the most boring thing in the world, listening to 10 hours of nothing,” he said. “But then, about the second week of April, it just exploded. And we were getting thousands of things going over.”

Millions of birds migrate through Houston each spring. The majority of these birds migrate at night under the cover of darkness, so little is known about the individual birds flying overhead, even to the most avid of birders. But now, a growing number of people like Lee are recording the calls these migratory birds make, and in doing so are helping researchers better understand this unseen migration.

Researchers have long relied on tools like weather radar to track how many birds are migrating and where they’re headed. But unlike audio recordings, radar can’t provide details on specific species, according to Benjamin Van Doren, a researcher at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

“We think (audio recordings) are a really exciting opportunity to tune into and understand bird migration in a way we haven’t really had access to before at a bigger scale than we’ve had access to before,” he said.

Van Doren is working on a project to automate the identification of these nocturnal flight calls using machine learning. He said his research relies heavily on birders like Lee who upload their recordings to Cornell’s online platforms, like eBird and the Macaulay Library.

“Amateur recordists have, I think, advanced the study of nocturnal flight calls even more so than professional scientists in recent years,” Van Doren said.

And interest in these recordings soared during the pandemic. In 2021, birders uploaded five times as many nocturnal recordings to eBird compared to 2019, according to Van Doren.

Van Doren said nocturnal flight calls and acoustic monitoring can help answer all sorts of research questions, and added that he thinks it will be especially key in studying how climate change is impacting the migration timing of specific species.

“There are a lot of interesting research questions that this opens up for us, such as how species are changing their timing of migration with respect to climate change, or how they interact with each other during migratory flights, which is something we still don’t fully understand,” he said. “We really don’t understand why exactly birds are giving these flight calls in the first place sometimes.”

A Rose-breasted Grosbeak spotted in a Friendswood backyard. These birds from South America to the Northern US and Canada for breeding. Courtesy of Chris Bick

Ornithologists in Houston also see the potential for these recordings to help with local conservation efforts.

“I think there’s a great opportunity to bring awareness to this unseen migration,” said Richard Gibbons, the Gulf Coast Manager at the American Bird Conservancy. “It puts names to all of those numbers.”

The recordings can provide data on which species are passing through cities and which are stopping in parks and nature reserves to refuel for their journey, according to Kelsey Biles, the Conservation Director at Houston Audubon.

“We’re trying to understand who’s migrating where, where they’re going, and how they’re navigating the landscape,” Biles said. “So what particular birds are really prone to going through cities and which ones to avoid them?”

Biles said there are limits to nocturnal recordings since not all birds call at night, but it’s a powerful complement when combined with other tools such as traditional birding.

“They tend to kind of work together so we can get a bigger picture all over of how birds are migrating to urban landscapes, and how they’re using stopover points,” Biles said.

Beyond the research element, birders say there’s something magical about identifying the bird calls.

“Once you start, you can’t stop because every night is something different,” said Lee, the Rice geology professor. “It’s so exciting.”

Lee said his entire setup cost him about $200. He uses a Zoom recorder covered in a waterproof plastic bag with a shotgun mic and attaches both of those to a window washing pole, pointing directing towards the sky.

Lee said setting up the equipment is pretty easy for anyone to do.

Lee attaches his recording equipment to a window washing pole on April 12, 2022.

Lucio Vasquez / Houston Public Radio

The hardest part, however, is learning to identify the calls, according to Friendswood resident Chris Bick.

“The learning curve for it is pretty massive,” Bick said.

Bick was working as a police officer at Rice when he met Lee, and is now recording nocturnal flight calls from his backyard, which he’s turned into a bird oasis with native plants, running water and bird feeders.

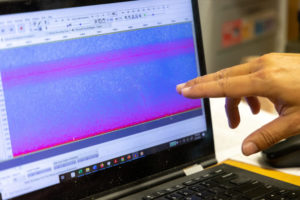

The recordings are uploaded to audio editing software, where birders learn to read the spectrograms and quickly identify the calls. There are dedicated Facebook support groups and guidebooks with images of what each bird call looks like to help.

Bird calls are analyzed using audio editing software. Taken on April 12, 2022.

Lucio Vasquez / Houston Public Media

“When I first started, it would take me probably about four or five hours just to get through one night,” Bick said, adding that now he can get through 3 hours of recordings in about 30 minutes.

Bick said was awe-inspiring to capture an American Golden plover as it flew over his backyard while traveling from South America to Canada.

“It’s kind of like a bird treasure hunt. You’re just going through (the recordings) and seeing what’s flying over your house,” Bick said. “And that’s the fun part about it is seeking out those calls.”