Listen to part 2 of this series in the audio player below:

‘It’s like a sweatbox’: Houston bus stops reach dangerous temperatures this summer

An original study by Houston Public Media set out to answer whether bus stops ever reached dangerously hot temperatures and how effective bus shelters are at cooling riders during the hottest times of the day.

Lucio Vasquez / Houston Public Media

A woman waits in the shade away from a bus stop until the bus arrives.

This is the first of a two-part investigation into the impact of extreme heat on Metro riders. Listen to the podcast, Hot Stops: How Houston Bus Stops Get Dangerously Hot.

It was a hot summer day and Glory Medina and her daughter Jade, who was 3 at the time, were running a quick errand at the grocery store near their apartment in Gulfton. They had taken the bus and once they arrived, the two of them faced a giant unshaded parking lot, the black asphalt radiating heat into their faces as they walked across it.

The blast of AC felt cool as they entered the store, and Medina bent down to lift her daughter into the grocery cart. That’s when she noticed Jade’s face was red, almost purple.

“I got scared,” Medina said in Spanish, remembering that day four years ago.

Grabbing a water bottle from a fridge near the checkout lines, Medina quickly twisted off the cap and doused her daughter with cold relief.

Glory Medina and her daughter at a bus shelter, July 2023.

Katie Watkins / Houston Public Media

“I just grabbed the bottle and poured it on top of her because she was as red as a tomato,” Medina said, adding that she paid for the water afterwards.

Her daughter was on the verge of heat illness. And Medina knew this because she too has suffered from heat illness multiple times. The worst, she said, was last summer when she collapsed at an intersection before crossing the street.

“You don’t think that can happen on such a short trip from your house,” she said. “But it does.”

A records request of 911 calls to The Houston Fire Department in June and July show at least 16 emergency calls were made from the bus or the bus stop for people experiencing “Temperature Related Problems.”

This number is almost certainly an undercount. Over 200 calls from that time period were under general categories like “sick person,” “unconscious person” and “fall,” or more specific descriptions that could be related to heat illness like “heart problem” and “syncope.”

Plus, this data only captures those who called for help.

“I said ‘please, don’t [call 911],” Glory Medina remembered saying after she passed out last summer. “I didn’t have health insurance at the time and I knew I just needed water. I wasn’t going to go to the hospital for water.”

Many more have experienced headaches, migraines, dizziness and skin irritation, including several riders we interviewed at the bus stop.

Houston Public Media conducted an investigation looking into the impact of extreme heat on METRO riders in Houston and whether enough is being done to keep riders out of harm’s way.

Our investigation revealed the dangerously high temperature that Houston bus stops can reach. In a first-of-its-kind pilot study, we measured temperatures at 21 bus stops in late July and early August.

• 73% of temperature readings inside bus shelters reached thresholds that put people at “extreme” risk for heat illness.

• In 16% of cases, the bus shelter made the heat worse, meaning it was hotter inside the shelter than standing outside in direct sunlight.

“To my knowledge, there’s been no studies like this,” said Kevin Lanza, an assistant professor at UTHealth Houston School of Public Health, who provided guidance on our methodology and has conducted research related to heat and bus stops in Austin.

He highlighted the data point — 16% of bus shelters made the heat worse.

“That’s a tragic design flaw. That’s a heat health issue,” he said. “And so, this is exciting because it provides us as scientists and practitioners with real evidence to think through what we can do with these data moving forward.”

Our findings aligned with what we heard from some riders – that bus shelters can sometimes turn into “Easy Bake Ovens” or “sweat boxes,” leaving many seeking shade elsewhere.

“We look for shade nearby,” said Gulfton resident Isabel Villalobos in Spanish. “We don’t go inside the bus shelter because it feels steamy there.”

Many bus shelters do provide shade and a respite from the heat for riders. But when they don’t, riders often wait for the bus outside of the shelters, finding shade in the shadows the structures cast behind them or underneath a nearby tree.

Lucio Vasquez / Houston Public Media

Pamala Henn was waiting for the bus at a stop in August.

“If there is a bus shelter, I’ll wait under (it), but it doesn’t really do much to help,” said Demarie Nevels from Sunnyside. “There’s no air flow.”

Most public transit riders in Houston rely on the bus — almost 70% take it at least 5 days a week. Even in car-centric Houston, people take the bus around 4 million times a month.

There are several ways that time in the heat adds up for transit riders during a commute. Almost all walk to the transit stop. About a quarter of riders need at least one transfer, which can mean extra time waiting outside. Roughly half of rides are on buses that come every 20 minutes or more on weekdays.

The impact of extreme heat on transit riders is projected to worsen with climate change. Houston just experienced one of the hottest summers on record, marked by a relentless string of heat advisories and triple-digit days that lasted for weeks.

Currently, just 23% of the more than 9,000 METRO bus stops have bus shelters. The rest are poles in the ground with a sign.

The agency is investing in thousands of bus shelters in the coming years to address this issue.

“Where feasible, where possible, we will have a shelter at every stop,” said Kenneth Brown, METRO’s Director of Service Enhancements. “We want to provide the most comfortable trip possible because we’re competing with the private vehicle.”

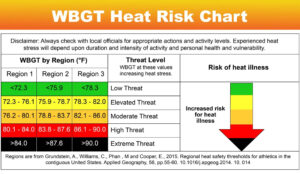

Houston is in Region 3.

WBGT: The Heat Metric Of The Future

Our pilot study measured bus stop temperatures in a metric called Wet Bulb Globe Temperature. WBGT offers a fuller picture of the elements that heat or cool the body when outside: solar radiation, air temperature, humidity, wind speed, and cloud coverage.

“The usual thermometers are about 10% of the whole story,” said Ariane Middel, an urban climate researcher at Arizona State University. “There’s so much more that’s going on when we’re outdoors. When we’re standing in the direct sun, we get a lot of additional energy from the sun that directly hits the skin and heats us up.”

Middel added the primary way that bus shelters mitigate heat is by shielding riders from solar radiation and providing shade.

Meteorologists are calling WBGT the “future of forecasting.” The best way to understand WBGT is to think of it in terms of threat categories, similar to the hurricane warning system.

Temperatures above 90° WBGT in Houston put people at an “extreme” risk of heat illness or the black category, according to a chart on the National Weather Service website.

The chart was originally designed for athletics, but meteorologists say extra precautions should be taken during any outside activity when temperatures reach the black threshold.

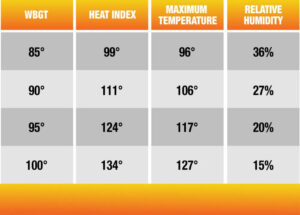

“A WBGT of 90 is actually quite bad, it’s a really high heat stress day,” said Tim Cady, a meteorologist with the National Weather Service’s Houston/Galveston office. “90° WBGT when you compare it to the heat index doesn’t really sound quite so extreme to most members of the general public that aren’t familiar with the parameter.”

When it’s 90° WBGT on a sunny day that could mean the heat index is 111. Here are other examples using the daily high temperature, relative humidity, and heat index.

Into The Black: Our Data Analysis

Into The Black: Our Data Analysis

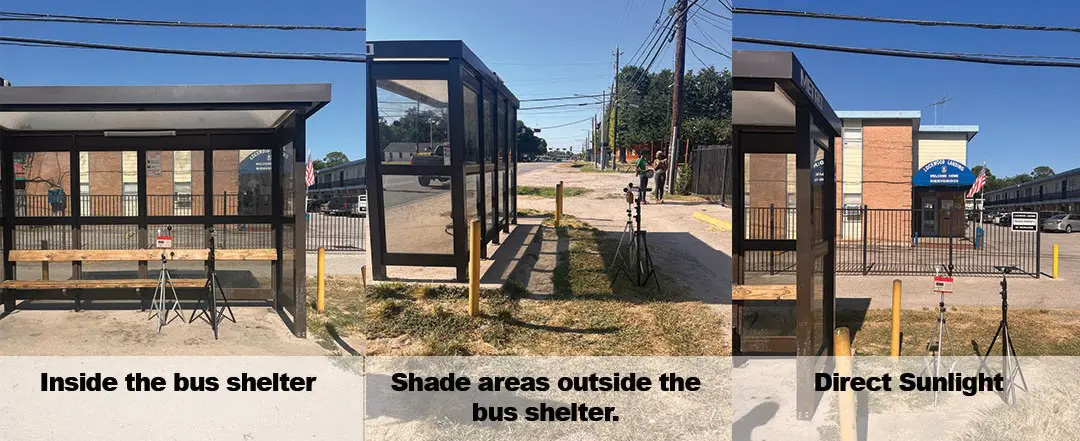

We took WBGT measurements in three spots: inside the bus shelter, outside the bus shelter in shade (when available), and in direct sunlight. These positions allowed us to compare the effectiveness of bus shelters with other sources of shade. Temperature readings in direct sunlight provided a baseline approximation of how hot the stop would be if there were no shelter to begin with.

We found that Houston bus shelters inconsistently provided protection against the heat, often entering the black category and posing an “extreme threat” of heat illness.

An overwhelming majority of temperature readings inside bus shelters – 73% – exceeded 90° WBGT. Temperatures inside the bus shelter ranged from 82.4° to 103.3° WBGT.

WBGT temperatures were taken in three spots at the bus stop.

Overall we found:

• Temperatures in bus shelters often entered the black category, averaging 91.4° WBGT.

• Tree shade nearby rarely entered the black category, averaging 87.1° WBGT.

Comparing bus shelter shade and tree shade:

• Bus shelters often helped:

· 60% of bus shelter readings reduced temperatures.

· Bus shelter shade was on average 2.6° WBGT cooler than direct sunlight.

· However, when the sun was shining into the shelter, temperatures were on average 3.7° WBGT warmer than direct sunlight.

• But tree shade was twice as cool:

· 100% of tree shade readings reduced temperatures.

· They were on average 5.6° WBGT cooler than direct sunlight.

You can read the full details of how we conducted the data collection here. We consulted with three heat researchers in academia on the prototype. Click here for the raw numbers from our data collection.

In the best-case scenario, bus shelter shade provided a cooling effect of 9° WBGT. But in the most extreme cases, bus shelters made the heat much worse, up to 8° WBGT hotter than standing directly in the sun. The hottest temperature we recorded inside a bus shelter was 103.3° WBGT.

“When I saw you recorded up to 103° – I mean that’s frightening,” said meteorologist Matt Lanza with Space City Weather.

Lanza said he was impressed by how much cooler tree shade was – enough to bring the temperature down a category or two.

“I really think that the tree part is very, very important, especially in an urban city like Houston,” he said. “You’ve just taken extreme heat and made it more tolerable. That’s a very big deal.”

Temperatures can range dramatically. Left: Bus Stop at Westheimer and Post Oak Blvd in Uptown. Right: Bus Stop at Westheimer and Fountainview Dr. in Uptown.

Brian Stone, the Director of the Urban Climate Lab at Georgia Tech University, was shocked by the number of readings above 90° WBGT.

“Well, that’s horrifying,” he said. “I don’t know any chart that says you should be outside. You don’t have to be moving around as an elderly person with a heart condition to be in a danger zone at 90. This is really dangerous.”

ASU Researcher Ariane Middel said although the recorded temperatures are high, duration plays a key role in the onset of heat illness.

“Everything that’s above 90 is considered extreme, no matter what,” said Middel, but emphasized that a short wait at a bus stop with frequent service wouldn’t be as concerning.

A walk or bike ride to the bus stop should be part of the equation, she added, because physical activity on top of a long wait time could result in extra strain on the body.

“I would say it just adds up,” she said. “It’s not that somebody would die at a bus stop just from waiting, but it’s just very uncomfortable.”

Houston Public Media sent METRO a description of the pilot study and key findings. We offered to provide a copy of our methodology with a description of the device we used, to walk through our data analysis and answer any questions. When asked if the agency found the readings alarming or if they planned to do anything with the data, Spokesperson Tracy Jackson responded in a statement:

“Without independent verification that your findings are accurate, it wouldn’t be prudent to comment on the temperature readings you provided in an email. Because we don’t know what kind of device was used to measure the climate inside a shelter or any of the other variables that could impact the readings, your methodology and spreadsheet would not bear any significance.”

Jackson said they are working on a pilot project for a shelter with a solar-powered fan. She mentioned METRO’s Urban Design division, which created a design manual with ideas for integrating trees and green roofs into bus stop design. However, this team is in its “infancy” and has not pursued any projects related to bus shelters yet.

Jackson also highlighted METRO’s initiative to add more bus shelters to the system. The agency plans to install 2,000 bus shelters over the next five years beginning this month. That means nearly half of the system’s bus stops will be equipped with a shelter.

Kenneth Brown, Director of Service Enhancements, said the shelters are primarily designed to protect riders from the elements like rain and the sun.

“That’s the biggest thing, protection from the elements,” Brown said. “We do have some extreme weather here in Houston, so having some level of protection is good.”

But further questioning revealed that protection from extreme heat isn’t a main factor when choosing the design for these new shelters.

The new shelters METRO will be rolling out are based on Type 4, the most common design out of more than 16 types of bus shelters across Houston.

An example of a METRO Type 4 bus shelter.

Temperature readings at these bus shelter types were among some of the hottest in the pilot study. In several cases, these shelters made the heat worse, exhibiting temperatures hotter than direct sunlight.

Type 4’s have a dark-colored frame with three clear panels and a partial cantilever. The new shelters will largely remain the same. The major differences include a new color, more durability and a gutter system that catches fewer leaves, said Shri Reddy, the Executive Vice President of Planning, Engineering and Construction. Heat protection was not included in his list of reasons why this design was chosen.

During interviews, Metro officials emphasized that bus shelters undergo rain tests to ensure they don’t leak during downpour. However, when asked if similar tests are done to see how effective shelters are at providing shade or heat mitigation, Reddy said it’s not part of the design process.

“In terms of a test of how much light or heat comes in, I am not aware we really have a criteria for that,” he said.

Cooling an outdoor space is inherently a challenge, added spokesperson Tracy Jackson during that interview.

“This is an open structure outside, it would be like trying to air condition a parking lot,” she said. “So there’s got to be some reasonable expectations about what we can do.”

The Easy Bake Oven Effect

There were five instances of bus shelters making the heat worse – when temperatures inside were significantly hotter than standing in direct sunlight. All of these readings were taken during rush hour and shared a few additional things in common. The bus shelters were located on streets running north and south. There was little or no shade inside the shelter. And the bus shelters had clear plexiglass-like panels on three sides.

Our theory is the transparent walls of the shelter are creating a greenhouse-like effect by trapping the heat inside. This coincides with high temperatures from the hottest time of day.

The position of the sun during rush hour means shade isn’t available in certain shelters.

“That shows you the orientation of these bus shelters is really important because the bus shelter is not useful if the sun’s shining right into it,” said Ariane Middel, from ASU. She said in addition to the heat from direct sunlight, there’s also heat radiating from the sides.

“The walls heat up and that heat radiates back into your body,” she said. “You’re just really not getting any relief from the bus shelter. It’s meant to give you relief but it’s not doing that.”

Middel said the shelter walls could also be blocking the breeze from getting inside.

One of the shelters with this greenhouse-like effect was located on Lockwood Drive in Kashmere Gardens. A similar bus stop sat two blocks away on the same side of the street. However, there was one noticeable difference: a big tree casting shade inside.

Temperatures were taken at both shelters on the same day around the same time. The results differed greatly.

Houston Public Media

Left: Bus Stop on Lockwood Drive and Cavalcade St. Right: Bus stop on Lockwood Drive and Rand St.

“So many bus shelters are built of that glass (like material),” said meteorologist Matt Lanza. “Maybe that is not the best way to do it because you’re inadvertently making it worse in the summertime for people that have to wait. Maybe instead you have something that is more reflective of the sun and then you add trees.”

Shri Reddy with METRO said one reason the agency uses see-through material for the side walls is safety.

“If we make the shelter opaque, it introduces issues in terms of safety because people want to be able to be seen,” Reddy said. “And operators want to be able to see who’s out there right for somebody to pick up.”

The Health Effects Of Heat

The longer someone is exposed to extreme heat, the higher their risk of getting sick. Individual factors like age, chronic conditions and taking certain kinds of medications can also impact one’s susceptibility to heat illness.

“I could list about 12 factors just off the top of my head that make people more or less susceptible to heat,” said Dr. William Perkison, who has studied heat stress on workers at UTHealth. He mentioned factors like pregnancy, obesity, chronic kidney disease, high blood pressure and more.

Heat exhaustion and heat stroke are two of the most serious types of heat illnesses. They include symptoms like muscle cramps, headaches, dizziness, fainting, nausea or vomiting and can progress to confusion, delirium and a very high internal body temperature. Untreated heat stroke can lead to organ failure, a coma or death.

A more mild form of heat illness is heat syncope — what Glory Medina from Gulfton likely experienced when she passed out. The illness refers to fainting caused by low blood pressure as the body circulates blood to try to cool itself down.

A handful of bus riders told Houston Public Media about the other ways waiting in the heat for the bus negatively impacted their health.

“The last time I was trying to get the 32 my head was hurting, I couldn’t stand it,” said Juana Alberto Mendoza, who was standing at a bus stop in Gulfton. “It was too hot. I was so dizzy. Thank God a guy (got out of his car and) gave me some water.”

Stephanie Hernandez in Kashmere Gardens said she’s also gotten headaches while waiting for the bus.

“I felt lightheaded or like recently I’ve had migraines for a while,” she said while waiting for the bus on Lockwood Drive. “I feel like it’s because of the heat.”

Lucio Vasquez / Houston Public Media

What’s (Metro) Next?

Riders will be increasingly exposed to extreme heat as climate change makes longer heatwaves and hotter temperatures the new normal in Houston.

Part of Houston’s Climate Action Plan includes cutting transportation emissions from cars and improving public transportation. To transit advocates and riders, making the bus a better option means making the heat more bearable.

“Transit riders are at the front lines of the heat and climate crisis,” said Gabe Cazares, the Executive Director of LINK Houston, a public transit advocacy group. “Too many METRO stops lack shade or shelters. Every minute waiting for the bus is a minute exposed to the elements.”

Cazares said one way to reduce time spent in the heat is to increase bus frequency.

“We must improve transit services overall,” he said. “Better, more frequent, more reliable service means less waiting in the heat, fewer cars on the road and a cooler climate.”

METRO is working on plans to increase bus frequency on key routes through its METRONext plan, which voters approved a $3.5 billion bond for in 2019. The plan includes improvements to 17 high-ridership bus routes to make them faster and more reliable.

It also includes adding better amenities to each stop, such as accessibility improvements for disabled people, bus shelters with built-in lighting, and digital signage.

Beyond more frequent service, another solution for the heat is to improve access to shade by rethinking shelter design or adding other sources like trees.

“(The heat) is something we absolutely have to think about and do everything that is within our power to try to make that heat more bearable,” said Christof Spieler, a former METRO board member and urban planner who has written extensively about transit systems across the U.S.

He thinks bus shelter designs often overlook extreme heat.

“I would say actually, as a general statement, I feel like we don’t think enough about shade with bus shelter design,” Spieler said. “I think most bus shelters are designed more to protect against rain than to protect against the sun.”

Spieler said addressing extreme heat for bus riders needs to go beyond just shelter design and requires a holistic approach.

“This isn’t the thing where there’s like one miraculous solution that solves transit in the heat, it’s a lot of little things added together,” he said. “You make that service more frequent; you make the passenger information a little better; you make the shelter a little more shaded; you have street trees on that street. And suddenly you go from an experience, which is absolutely miserable, to an experience, which is acceptable.”

If you found the reporting above valuable, please consider making a donation here. Your gift helps pay for everything you find on texasstandard.org and Houston Public Media. Thanks for donating today.