This week, the Nobel Foundation has been awarding its prizes for advancement in science and medicine. Nobel Prize winners become world-famous for their discoveries and contributions to their fields. But looking back on past winners, not every discovery has stood the test of time.

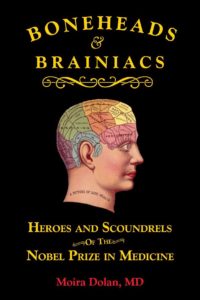

Dr. Moira Dolan wrote about these Nobel “failures” in her book, “Boneheads and Brainiacs: Heroes and Scoundrels of the Nobel Prize in Medicine.” She told Texas Standard that the prize is supposed to go to a maximum of three recipients for their work over the last year. But some discoveries, in retrospect, weren’t successful and were even dangerous. Take the lobotomy – Antonio Egas Móniz received the prize in 1949 for that procedure, which intentionally damages tissue in the prefrontal lobe to alleviate symptoms of mental illness. Lobotomies are uncommon these days, and many countries banned the procedure.

Dr. Moira Dolan wrote about these Nobel “failures” in her book, “Boneheads and Brainiacs: Heroes and Scoundrels of the Nobel Prize in Medicine.” She told Texas Standard that the prize is supposed to go to a maximum of three recipients for their work over the last year. But some discoveries, in retrospect, weren’t successful and were even dangerous. Take the lobotomy – Antonio Egas Móniz received the prize in 1949 for that procedure, which intentionally damages tissue in the prefrontal lobe to alleviate symptoms of mental illness. Lobotomies are uncommon these days, and many countries banned the procedure.

“[It’s] sticking, basically, something that looks like an apple corer or an ice pick right under the eyebrow bone and scraping it back and forth to destroy the white matter of the frontal lobe,” Dolan said.

Ironically, years earlier in the 1920s, Móniz invented cerebral angiography – a method to make it easier to see the blood vessels in the brain. It’s an imaging technique still used today, but he never received a Nobel Prize for that.

Then there are the prizewinners whose medical advancements don’t attract the notoriety they deserve. Niels Ryberg Finsen discovered light therapy for smallpox and tuberculosis lesions, which can be debilitating. Finsen was awarded the 1920 Nobel prize, but the U.S. Food and Drug Administration suppressed his technology for years, Dolan said. Now, there’s “renewed interest” in light therapy for many conditions, including antibiotic-resistant skin infections, lung damage and to help activate cancer drugs.

“You know, it can go both ways with the Nobel Prize,” Dolan said.