Massiel Vargas took a single breath, then gulped for air. She angled her brown eyes upward to try to dam up her tears. Then, they spilled.

Reunited in a WhatsApp call with her oldest child, she looks back with relief and remorse at his journey. Relief that he made it safely from Central America to the U.S. Remorse because she knew she had to let him go, but she misses him. Oscar doesn’t face gang recruitment any longer, but she lost her rock.

Now, sitting in her turquoise living room in Honduras and peering through the video screen, she sees that her son looks sad, like he wants to hug her through his screen in Indianapolis, an impossible distance of some 3,000 miles.

She remembers the Wednesday morning in February her Oscar left for Texas. It still fills her with pain.

“You don’t know how it will go on the journey,” the single mother says of her first-born son’s passage. “I see little hope in this country,” she said. “He would not succeed as he wants and I want.”

In late March, Oscar joined an exodus of mostly Central American youth travelling without a parent to seek asylum and a new life in the U.S. It’s unprecedented in scope. More than 55,000 unaccompanied minors have arrived since President Joe Biden took office.

The heartache and hurdles for Oscar and his mother illustrate why so many are leaving and the persistent challenges this mass migration presents for the children, ther families and those who receive them in the U.S. Federal authorities have been overwhelmed by the number of children, opening more than a dozen unlicensed temporary shelters for them, including one in Dallas since closed and a massive detention facility at Fort Bliss in El Paso.

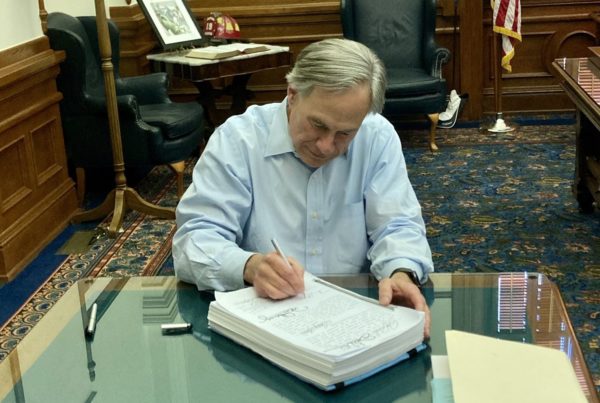

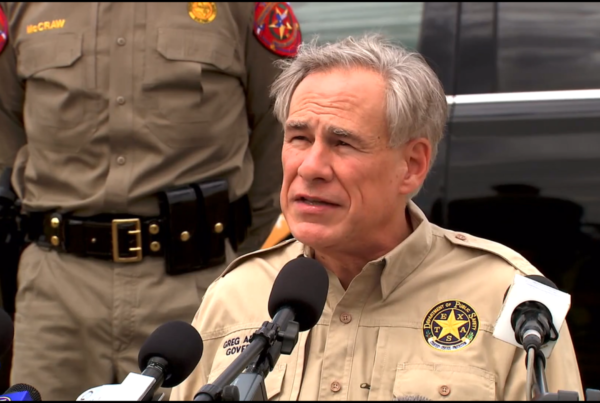

Their arrivals are now complicated by an order by Texas governor Greg Abbott to yank state licenses for the more permanent shelters that have been holding many of the children before they are typically released to family in the U.S. while awaiting the outcome of their cases.

Nearly one out of three of the minor children, like Oscar, now comes from Honduras.

Flight From Honduras

Oscar says he left Honduras when he ran out of good choices there. The coronavirus pandemic and a pair of devastating hurricanes wrecked the already faltering economy. His mother had little work. He never had a relationship with his father. Gangs tried to recruit him.

He knew some of the gang members from his childhood. “They say join them, work with them,” Oscar says, his voice getting lower. “I didn’t listen.”

With his high school shuttered because of the pandemic, Oscar decided to head north. He hopes to finish in the U.S., where he is safe.