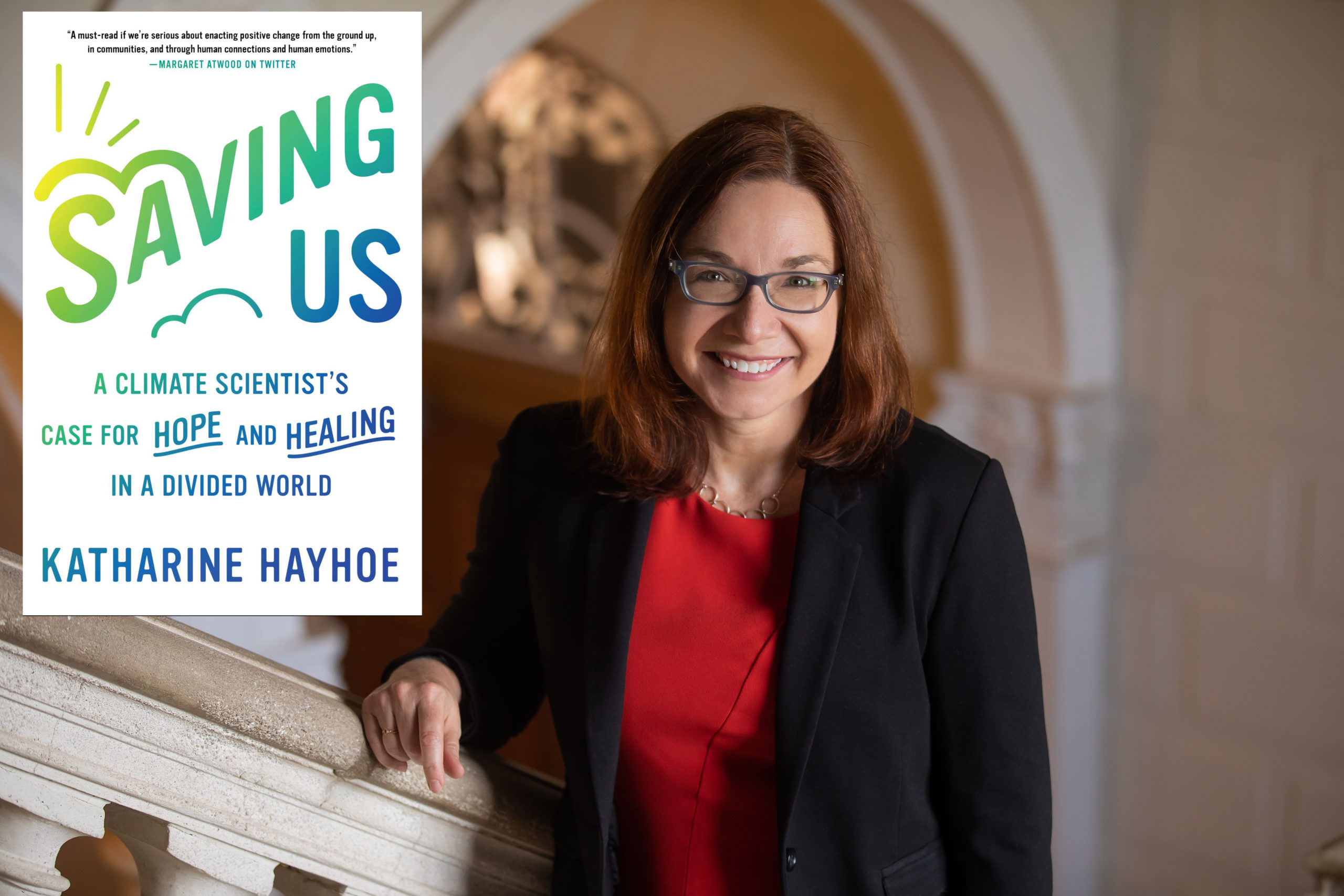

Katharine Hayhoe has become one of the country’s leading voices on climate.

But her latest book isn’t as much about the changing climate itself as it is a discussion of how to talk about the sometimes fraught topic of what’s changing. It’s called “Saving US: A Climate Scientist’s Case for Hope and Healing in a Divided World.”

Hayhoe is an endowed professor of public law and public policy at Texas Tech University.

Listen to the interview above or read the transcript below to hear what Hayhoe says about communicating with one another better about the consequences of climate change without ending up in arguments.

This transcript has been edited lightly for clarity:

Texas Standard: You write that the most important thing individuals can do to help with the climate crisis is to talk about it with the people around them. How is that useful?

Katharine Hayhoe: The loudest voices on both sides of the fence are hurling stones each other on social media and other places. But the vast majority of us are in the middle. We’re worried about this thing and we never talk about it. Only 14% of people talk about climate change across the whole U.S. And our number is no different in Texas. We don’t do it because we don’t want to pick a fight and we don’t want to get depressed. And I don’t either. I don’t want to just have a conversation to come away feeling like I want to pull the blankets up over my head. So I’m not talking about taking a fight. I’m talking about beginning with something we agree on, like the place where we live or what happened to our family last time a hurricane hit the Gulf. Or, man, that was a bad drought. I hope it doesn’t come back again. Connect the dots to how that’s changing and then talk about something incredibly positive that either we can do ourselves or our school or our town or city is doing or our state is doing. There’s a lot of good news in Texas that nobody knows about.

Hit us with some of that good news. I think a lot of folks could use some.

We get 23% of our electricity from wind and solar. We’ve been number one in wind for a long time. Fifty years ago, we weren’t even in the top 10 list for solar. We are now number two and we’re moving up. They’re building the biggest solar farm in the United States just outside of Dallas. And we’ve got the biggest Army base in the U.S., Fort Hood. It is powered 42% by clean energy and it is saving taxpayers tens of billions of dollars.

Can you tell us about some of the techniques you’ve developed to speak about climate change to folks who might bristle at the term itself?

One of the things we can do is don’t even use the words climate change if that’s what’s going to set people off. Talk about how the weather is getting weirder and talk about how it’s affecting you, or your family, or your kid, or your crops or your water. Then talk about things that people are doing. In West Texas, there [are] farmers who are adopting smart agriculture practices where they use cover crops to enrich their soil, to reduce their drought risk and to suck carbon out of the atmosphere.

In the course of communicating about the climate, I wonder if there’s a story that has sort of stuck with you.

I have conversations and engagements with the “seven percent” on a daily basis daily. They are the people who cannot leave [the] topic [of climate change] alone. They are always on Facebook. They’re always talking to you about how it’s a hoax and those scientists are making it up. And somebody wrote a book saying it was just solar cycles. It takes a miracle to have a conversation with a seven percenter that goes well.

A lot of it is on social media, on Facebook or Twitter. I get handwritten letters and typed letters and emails and phone calls to my office, some of them so horrible that I couldn’t even say half the words on the air.

So that definitely happens. But in the book, I have so many positive stories. Probably one of my favorites is the one about John’s dad. So my colleague John has a dad – who, every time John went home for dinner – would be like, ‘well, John there are more polar bears now than there ever were. So how could you say the polar bears are endangered?” So John went back to school. He got a Ph.D. in cognitive psychology. He became a global expert in misinformation about COVID and climate change. Do you think that changed his dad’s mind?

Maybe no?

Right. That just shows you could be an absolute genius and you won’t change your own dad’s mind. But the story has a happy ending. So his dad was a thrifty, fiscal conservative. He saved money and he liked to be very independent. So one day his dad heard about how there was a rebate on solar panels for his rural area. And he crunched the numbers and he figured he’d save some money. He ended up saving more and more money than he thought. And every month, sending John his power bill, saying “look how much money I save. This is great.”

How are you able to maintain a sense of hope about where we’re headed with the climate when you know about its consequences as well as anyone, and you’re constantly barraged by skeptics and cynics?

That question, what gives you hope, is one that I still hear every day. And I have heard it almost every day for the last four or five years. And so that ultimately is why I wrote the book. The book ultimately is about hope in this divided world that is just more and more divisive every year where all people are doing is just throwing stones at each other from the opposite ends of the backyard, it seems like.

With climate change, I actually find hope in the science and knowing that our choices matter. Our future is in our hands. We really can avoid the very worst of these impacts. But we have to act now.

As a human, I find hope in seeing what people are doing. I guarantee some of them are your neighbors and people you work with or people in your town or your city who are doing incredible things totally under the radar. And whenever I hear about something amazing that people are doing, that restores [my] faith in humanity.

But ultimately, as a Christian, my hope comes from – as it said in the Book of Romans – it talks about hope and it begins with suffering. It says suffering leads to perseverance, perseverance to character and character ultimately leads to hope. Hope is not positive circumstances today. Hope is that small, bright light at the end of the tunnel saying, “you know what, there is something better in the future.” Not just spiritually… but we know also in this world that we can live in a different way. We can show love for each other much more than we do today. We can consider others’ need before our own. And this truly is an opportunity in solving climate change for us to come together and focus on what really matters to us. We all want a safe place to live. We all want clean water to come out of the tap when we turn it on. We all want our children to have a better world to live in. And if we can focus on what we agree on rather than what we disagree on, what else might we fix along the way?