When they were married in 1967, Bernard and Shirley Kinsey set an ambitious goal: visit 100 countries together. While experiencing different places and cultures, the couple began collecting objects to remember their travels.

Over time, they amassed a sizable and critically celebrated collection of art and artifacts, now considered to be one of the most comprehensive surveys of African American history and culture outside of the Smithsonian.

With pieces dating from 1595 to today, the Kinsey African American Art & History Collection’s latest stop is in the Lone Star State, at Holocaust Museum Houston.

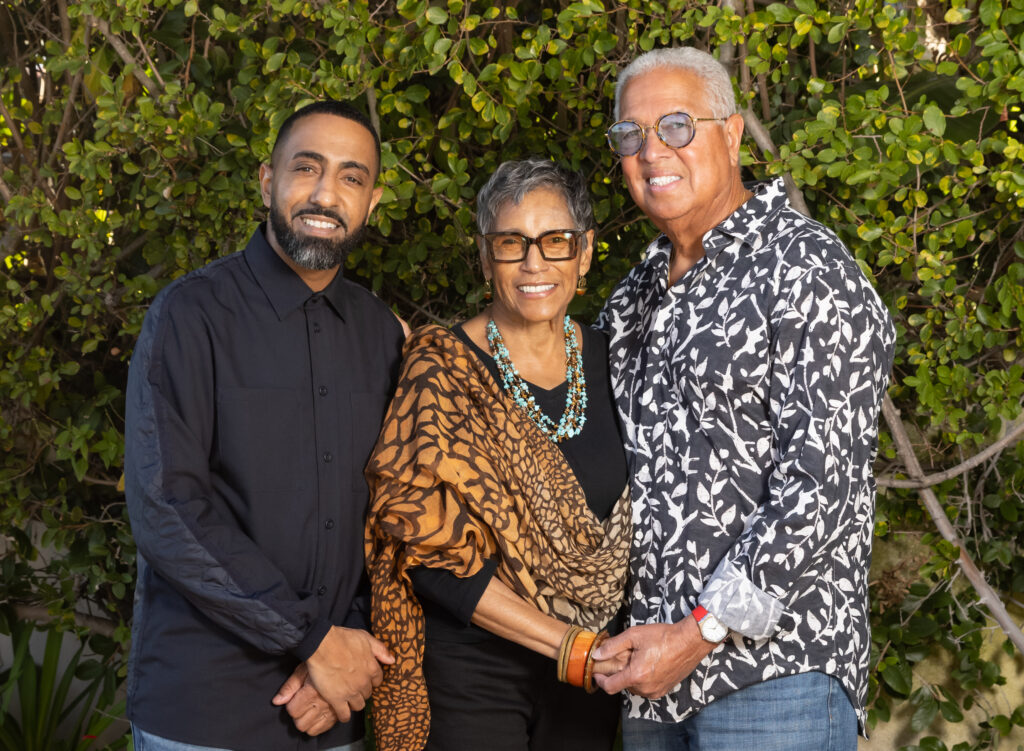

Shirley and Bernard Kinsey joined the Texas Standard to share more about the collection.

This transcript has been edited lightly for clarity:

Texas Standard: I have not seen the exhibit yet, but from what I have seen and certainly what I’ve read about it, this is quite the collection – over 100 works of art in Houston. Tell us about some of the highlights.

Shirley Kinsey: I’ll get started here, although I’m not going to start with my highlights just right now. I’d like to just say a little bit about how we got started. And it’s mainly because of our son, Khalil Kinsey.

We traveled quite a bit, but we realized while we were collecting all these items, a lot of it was about other cultures in whatever countries or cities we were in, and we realized that we didn’t know enough about our very own culture. And that’s when we really dove deep into finding more about our ancestors and those that I call our collective ancestry. We don’t know all of them, but they are part of who we are.

Bernard, what are some of your favorites in the collection?

Bernard Kinsey: Well, almost anything you can think about that describes the African American story. And that’s what the Kinsey Collection focuses on. It’s a concept called the Myth of Absence, which essentially says that African Americans are not part of the story and not part of the conversation, not part of the narrative in America. And what we strive to do, our family, the Kinsey family, is put us in the conversation and destroy the Myth of Absence.

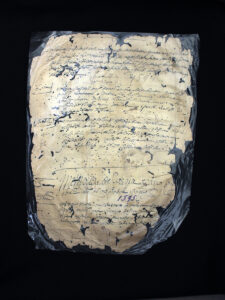

‘Baptism Record,’ 1595, St. Augustine, Florida, ink on paper. This is the earliest known Baptismal record of African American presence in what later becomes the present-day United States, establishing the existence of African Americans 12 years before the founding of Jamestown. Courtesy of The Kinsey African American Art & History Collection

For instance, our earliest document is 1595 – that is before Jamestown. We have an African American girl named Estebana, we know her name. We have a 1598 marriage certificate of a couple in Saint Augustine. So, we have a saying: there are the stories that made America and then the stories that America made up. And essentially everything most people got in high school history, in college was made up because Black people are not part of it.

We say simply that everything that happened in this country – everything, from architecture, carpentry, furniture, food, you name it – Africans brought this to this continent and made it better. And if you come and see us at the Holocaust Museum Houston, you’ll see this remarkable people called African Americans.

How do you go about putting together a collection that communicates this Myth of Absence? I would imagine it would be important to contextualize a lot of these pieces, right?

Bernard Kinsey: Yeah. It’s like being a detective. First of all, I’ve read literally a thousand books on the African American story, slavery, reconstruction, Civil Rights. And you come away that there’s certain pieces that really make up the foundation for the African American story and American history. Because really, this is not Black history. This is American history. And what we’re trying to do is put us into the story.

For instance, once you get past that Jamestown wasn’t the beginning of the African American story, you have to kind of dismiss most of the other stuff that they told you. And I’ll give you an example: We have the Three-Fifths Compromise. We have Phillis Wheatley, the first book written by an African American. We have the first scientific book written by an African American businessman, [Benjamin] Banneker. We have [Olaudah] Equiano, the first book written by someone that was below deck. We have Ignatius Sancho, who was born on a slave ship and the first person of African descent to vote in the election.

I mean, so that’s just in the first section. And so, we take transatlantic slavery, Civil War, we have a letter by Frederick Douglass, 1857, handwritten. We have Paul Robeson. We have so much. We have almost a thousand pieces.

We came to the Holocaust Museum. We have two Jewish painters in this show. We’ve never shown them before, but they’re appropriate for here. We have made this connection with the African American story and the Jewish community. And it’s a great story of partnership for many, many years.

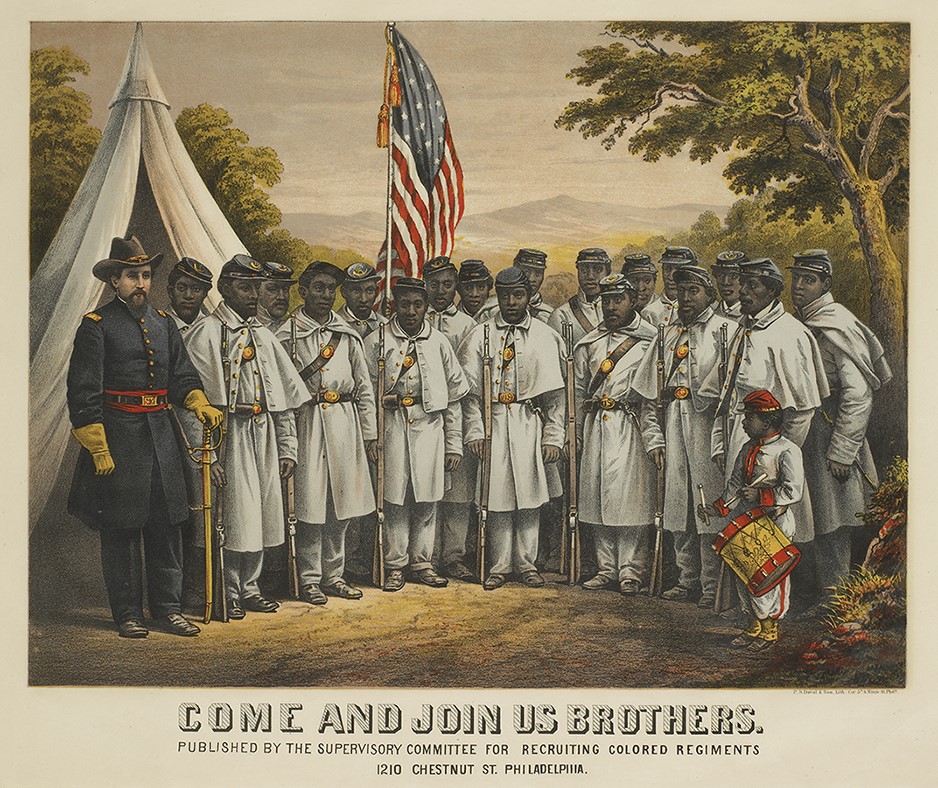

Do you know that when the concentration camps were liberated, there was the Black soldiers that did that? People don’t realize that Black troops were the ones that liberated Germany. The 369 Harlem Hill Fight was the first regiment to reach the Rhine River in the war. We’ve been cut out of that. That’s called the Myth of Absence.

And there’s so many opportunities for us to come together. And I think this day and time having these partnerships that are visible – I mean, we’ve been to Dallas. We did 125,000 people at the African American museum back in 2020. We’ve done 16 million people around the world, translated into Spanish and Chinese. And you’re not going to see this unless you get on a plane and go to the Smithsonian. End of story.

» GET MORE NEWS FROM AROUND THE STATE: Sign up for Texas Standard’s weekly newsletters

‘United States Soldiers at Camp William Penn,’ 1863.

Courtesy of The Kinsey African American Art & History Collection.

Let me ask you about how this got started and how it evolved. When did it dawn on you that putting together an exhibition of these works that you had been picking up and collecting was something that you wanted to do? Was there a moment or a spark that sort of made you think, yeah, we need to do this?

Shirley Kinsey: Bernard been a park ranger at the Grand Canyon – integrated the park ranger system, really, in 1966, the summer before we moved to California. And so our first effort at traveling was going to national parks. And I found that we were always interested in indigenous cultures. We’d do the Navajo, the Hopi information, and we’d go down to Mexico and find out about the Teotihuacáns and the Mayans and the Aztecs, and then we’d go to Canada and find out about the Eskimos and the Northwest Coast Indians and Inuits.

And Khalil was born 10 years after all of our immense traveling. And that was the dawning of things, really. He was born right after “Roots” had been on television [in 1977].

We realized that we had left Florida and left a lot of what we should have known about when we were growing up that we didn’t – a lot of things that our parents had never talked about because slavery was not anything that was really discussed at home. I grew up with my grandmother, and she never talked about it. Her parents had to have been just right at the tip of slavery, but she never talked about it, and I didn’t ask.

And so when Khalil was born, we said, you know, we need to find out a little bit more about who we are and where we come from. And that started it. Then when that family history report came about in about third or fourth grade and he came home with questions we could not answer – we couldn’t call Florida and get any answers. I had taught for five years before that time, and I said, listen, any report that you’re going to do is going to be on somebody Black. We’ll find out. We’ll go into libraries and museums and all these places and find information about our collective ancestry – people who were not enslaved at that time. And so all of his reports were done on that.

Bernard is the historian in the family. And at some point, something came across his desk that he just could not let go. And which really meant then, we started trying to fill in the gaps between that particular time and move forward with it. And he said being a detective, but it really was, “okay, this happened here. What happened next?” And then you look for that. A lot of times things began to find us, frankly – you don’t remember how or where all of this had come from.

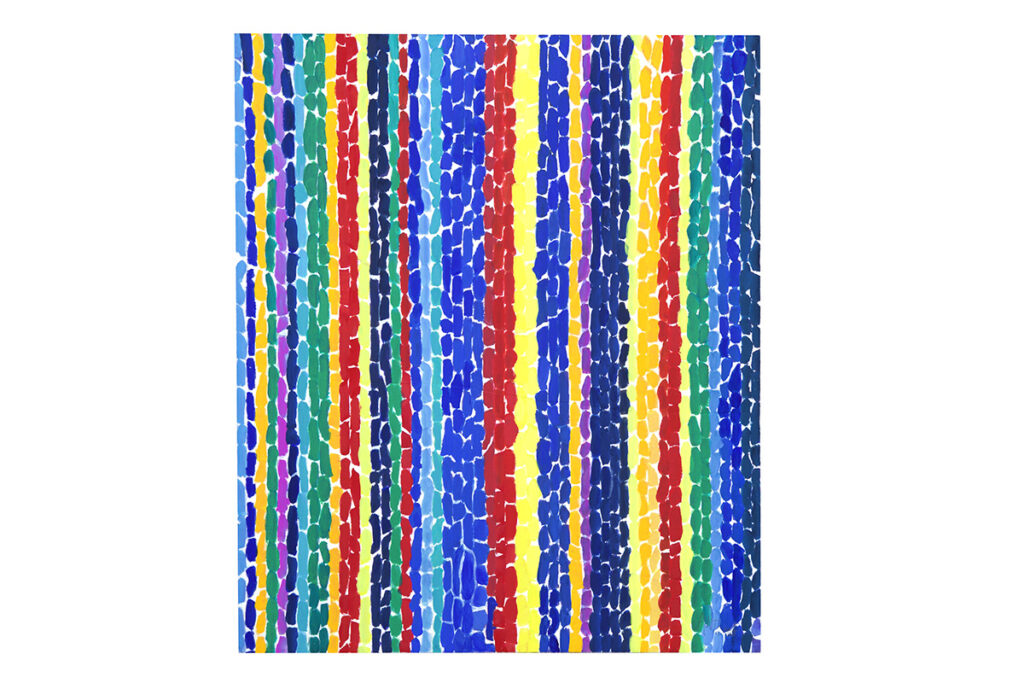

‘Untitled,’ 1970, acrylic on paper, by Alma Woodsey Thomas.

Courtesy of The Kinsey

African American Art &

History Collection

Obviously, part of the African American story and experience is the promise of freedom and the denial of that promise, or that promise not being fulfilled. But when you’re putting together an exhibit like this, of course, you want to invite people in to experience something that in a way takes them to another level, right? I mean, that’s something that you’re hoping for.

But is it hard to view some of these objects, these pieces in the collection, or did you specifically try to avoid certain pieces because they might they might upset folks? Or how did you think about that because you don’t want it to lean too much into, you know, one thing over obviously telling about the achievements as well.

Shirley Kinsey: My take on that is, well, when we realized – actually, when we were collecting, too, first started collecting – I always said I did not want us to focus just on slavery, the horrors of slavery. That’s horrible enough. I don’t want to have to have that in my space all the time. And so, I don’t want to really have to share a lot of that either. For me it was, horrors of slavery, okay, but that’s not all it is.

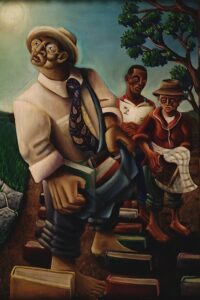

‘The Cultivators,’ 2000,

oil on canvas, by

Samuel L. Dunson Jr.

Courtesy of The Kinsey African American Art & History Collection

It focuses mostly on the accomplishments, the achievements of African Americans, who, against all odds, were able to succeed and accomplish and serve and build America to be what it is today. And having been a schoolteacher, also, I always realized that Black History Month – which started out as Negro History Week in 1926 by Carter G. Woodson – I used to always say, we only get information on three or four people to talk about the Black History Month for the kids. I don’t care what grade you’re in, that’s all you get.

So our Black kids grew up thinking that African Americans didn’t do anything, that all they were enslaved. Kids inside that class also grew up thinking the same thing. And so, as my son says, once you know more about me and my history and where I come from, and I know more about yours, we can see eye to eye.

Bernard Kinsey: We have a chance to be friends.

Shirley Kinsey: We have an equal, level experience. And, you know, Khalil grew up basically in Orange County …

Bernard Kinsey: In the white community.

Shirley Kinsey: … in Pacific Palisades, really high school years. And for the most part, a lot of times he was the only Black kid in his class, you know? Now, high school – Black kids were then bussed into where that school was. So, he was able, and he talks about it now, that once he got involved with really doing and working with us and doing the curatorial work, that he now stands taller, and he feels more empowered.

And these are the kinds of things that he tries to transmit to other kids, in that you have to know who you are and where you come from as much as possible. I said earlier that a lot of these images we have are not our people biologically, but they are our collective ancestry. And that’s what I focus on and that’s what I try and build on, which gives me hope.

Your son, Khalil, is your general manager. Did you have to twist his arm for – I mean, you know, young people, they have a lot of dreams and stuff …

Shirley Kinsey: A a few years ago, he used to say, if you’d asked me if I’d be working with my parents, I would’ve told you no. Because he had another whole life he was doing. He’s a writer, for one thing. And when we came out with the first edition of our book in 2009, I said to him, I needed him to work with the editor because she kept changing the way we phrase things, and I said it had to be in our voice.

He’d been gone for a while, and so a lot of the material had come in after he had left. And he said, Mom, when I sat there and had to read everything that’s in this book is when I really began to feel the change in me and know that you guys needed me to work with you on this and wanted to do it. Does it beautifully.

Bernard Kinsey: It’s a beautiful thing to you to have your son – well, for me, working with Shirley, um, I mean, we’ve known each other 60 years, and then now Khalil, and we have a new grandson that was just born who is half Jewish and half black.

We have the actual Doors of No Return from Slave Coast Castle in Ghana. And let me put that in perspective. So, when you come into the museum, you’re going to walk through the same doors that our ancestors walked through. 4.5 million people walked through these doors on the way to slave ships to come to the Americas.

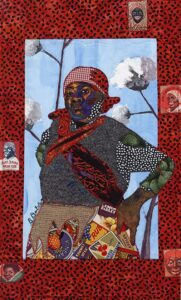

‘The Boss,’ 2006,

quilted cotton, appliqué, by Bisa Butler.

Courtesy of The Kinsey African American Art &

History Collection

And once you get inside, you’re going to see all the remarkable things that they did, even though they were under extreme duress. And that’s the story of empowerment that we want people to take away, not about struggle. We got to stop struggling so much. We got to get through it. And we like to show people having accomplished that.

So, when you dig into these pieces – when you see a Three-Fifths Compromise. Most people talk about the Three-Fifth Compromise – they’ve never seen it. They’ve never seen the Dred Scott decision or the Brown versus Board.

My dad sued the Palm Beach County School Board in 1941 because Black teachers made half of what white teachers made. Now, let me put that in perspective. When you go to Kroger, you don’t get a 50% discount because you’re Black. Okay? That’s a Black tax. And that tax is on Black people today all over America. The Navy Federal Credit Union today only approved 50% of their military veterans that are Black. They give the same loan to someone making $60,000 a year, white, that it takes a $140,000 being Black. That’s a tax.

So, what we’re saying, if Charles Tiffany sends his son $500 in 1857 to open a store on Broadway that later becomes the blue box that we all call Tiffany, and it’s all from slavery and cotton, you don’t think Black people have some interest in that? Brown University being Amos Brown, who is the biggest slaver in the 18th century – he brought 100,000 Africans to America and became rich. You don’t think Black people ought to go to Brown University?

This is all we’re talking about. It’s not freedom, but it’s equality, and the Kinsey Collection – and let me just say this, Shirley and I’ve been married 57 years. We’ve done everything America says you’re supposed to do, and we’ve done it impeccably. So, we know this story, and we believe that even though we’ve walked this very straight and narrow, that most people can’t do it because it’s too hard. So, we need help. We need help from all of our fellow listeners out there to come out and get the right information, so you can be able to understand what this struggle is about in America.

Shirley Kinsey: One thing I’d like to just add to this, though, is that for me, the collection strives to give our ancestors a voice, a name and a personality. And when visitors come through there, I’d love for them to be able to leave feeling educated, motivated and inspired by what they see there. Because it is about us coming together and understanding our American history, not just Black history.

And once we get past that – Khalil used to say to me, mom, I don’t know why we have Black History Month; it really is a joke, he said, because nothing ever happens during that time. And at some point, I would like to see America really get away from having to have any distinctions there, you know, because we’re just all people and we’re learning the same information so that we can have the same attitude about a lot of things. It’s going to be a long time coming, I know, but it’s hard. And with this young grandson of ours now in our life –

Bernard Kinsey: It’s aspirational.

Shirley Kinsey: I mean, it’s aspirational, and it’s really where I love to see us end up.

The Kinsey African American Art & History Collection is on display in the Josef and Edith Mincberg Gallery at Holocaust Museum Houston through June 23.