Earlier this year, U.S. Customs and Border Protection reported an increase of Mexican nationals crossing the border into the U.S. between March and May, raising concerns of COVID-19 spread into the United States. The concern prompted a collaboration between the Department of Homeland Security and the government of Mexico to expel migrants through repatriation flights to Mexico City.

It’s 11 a.m. on a mostly quiet Thursday morning at the second terminal of Mexico City International Airport. It’s a stark contrast to the always busy scene of a couple months ago, before the COVID-19 pandemic. The few travelers who wander through the gates all wear mandatory face masks.

Adán Jacome León, a volunteer with the activist group Deportados Unidos en la Lucha, hands out face masks at Mexico City International Airport to recently expelled Mexican migrants who crossed the border into the U.S.

Occasionally, a message is played over the intercom reminding travelers to practice social distancing and other safety measures to prevent the spread of COVID-19.

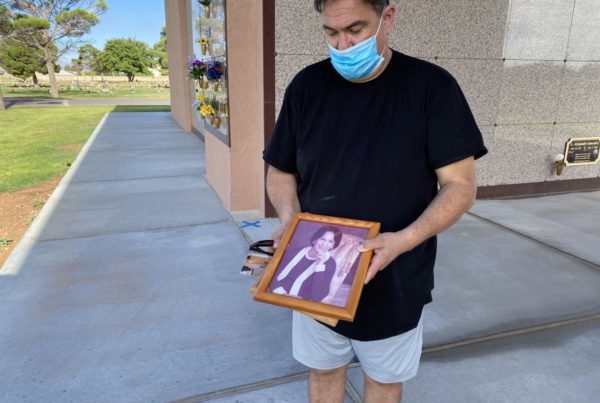

Adán Jacome León, a volunteer with the activist group Deportados Unidos en la Lucha, arrives at the airport at 11 a.m. Thursdays and Fridays to welcome expelled Mexican migrants who arrive through a tucked away gate in the corner of an otherwise empty hallway. Like all members of the organization, Jacome was deported from the United States. The group was formed by deportees to help others who are going through the same experience find resources like unemployment aid to create a new life in Mexico.

Adán Jacome León is a volunteer with activist group Deportados Unidos en la Lucha. He, like all members of the organization, was deported from the United States after living there for 16 years.

After living in Las Vegas for 16 years, Jacome had to leave his wife, who is a U.S. resident, and his U.S. born 6-year-old daughter. He hasn’t seen them in three years because he can’t enter the U.S., and said he doesn’t feel comfortable having them visit him in Mexico.

Four flights operated by ICE Air arrive weekly from San Diego, California or Brownsville, Texas. Jacome said migrants on board tell him they’ve crossed at different points along the U.S.-Mexico border.

“They are expulsions,” Jacome said. “There are also some [migrants] that have been detained for three, four months, and then there are others that are being detained because of COVID and expelled right away.”

Some of the passengers aboard the flights are deportees, who have been detained for months. Others are recent expelled migrants who only spent two or three days detained in the U.S.

Mexican nationals expelled from the U.S. after crossing the border illegally are flown into Mexico City after being detained by Border Patrol for only a couple of days. Their belongings are taken away, only to be given back in red mesh bags once they reach Mexico. The destination of the flights is unknown to them until after they have landed.

According to Jacome, those who wear green-coated paper bracelets have been in detention for awhile.

“Those with bracelets are the ones that have been detained for one or two months,” Jacome said. “Those without, might have been detained the day before yesterday.”

Volunteers with Deportados Unidos en la Lucha distribute fresh face masks to migrants. Jacome also passes fliers with Deportados Unidos’ contact information, in case some need help reestablishing themselves in Mexico.

After their planes land, officials from Mexico’s National Migration Institute break migrants into four groups, and send them to Mexico City’s biggest bus stations, including Central del Norte, the bus station that connects the city to Northern Mexico.

There, a young migrant from the Mexican state of Hidalgo, who wanted to remain anonymous to keep his identity safe, waits for his bus with others who have just landed in Mexico.

“They didn’t tell us anything, they just threw us in the plane and told us they were sending us back to Mexico,” the man said. “They didn’t say what was the destination.”

He crossed the border in McAllen, Texas and was detained for four days before he was put on a flight. Another migrant, who also asked to remain anonymous, said he spent two agonizing days and three nights walking through the desert after crossing the border through Tecate, Baja California. He was then detained for two days and was never allowed to shower while in detention.

The young migrant from Hidalgo said the flight was full. There were three people on each side of each row of seats, making it impossible to social distance. Everyone was seated, chained from their feet, hips and hands. He said the only COVID-19 precaution officials took on the plane was a blood pressure and temperature check before boarding. It wasn’t until landing that he found out they were in Mexico City.

U.S. Customs and Border Protection said in a statement, “The goal of these repatriation flights is to help reduce the spread of COVID-19 into the United States, as well as reduce strain on Mexico’s resources along the border.”

Adán Jacome León, the volunteer at the airport, said they are really just punishments.

“The punishment is that they send them all the way here,” Jacome said. “If they got them in San Diego and they’re from Zacatecas, or Torreon, they send them to Mexico City.”

Mexican migrants are sent to Mexico City’s biggest bus stations after being expelled from the U.S. on July 10, 2020, days after crossing the border illegally. Mexico’s National Migration Institute pays for their bus tickets so the migrants can reach their final destinations.

He said this is just a way to discourage migrants from crossing the border again because if the migrants are from far away cities, they’re now deep in Mexico City, a 14-hour drive from the U.S. So it’s especially hard for them to go back north to the U.S.-Mexico border.

However, some do go back right after landing in Mexico City, because Mexico’s National Migration Institute pays for their bus tickets to wherever they say is their destination.

If Jacome is right about the flights, the discouragement is working, at least with the man at the bus station. He’s getting a ticket to go back to his hometown in the Mexican state of Hidalgo. He said he left for the U.S. to find a better life. This was his first time trying to cross the border, but he said he won’t try again any time soon because it’s really hard to cross right now.