From Houston Public Media:

Before Breanna Chachere started medical school at the University of Houston, she experienced firsthand the gaps in health care access in Texas.

“I grew up in a family that had a lot of issues and prevalence of chronic diseases,” said Chachere. “I definitely grew up in a medically underserved city, so that often meant we had to travel outside of Alvin, Texas to get the medical care — quality care I would call it — that we needed.”

Before heading to the East Coast for graduate school, Chachere continued to see these health disparities show up while working at public schools in La Porte and Pearland. She said witnessing it in the Houston area drew her to the medical field.

“This is my community and it felt very natural for me to come home to study medicine in the place where I ultimately hope to practice,” said Chachere.

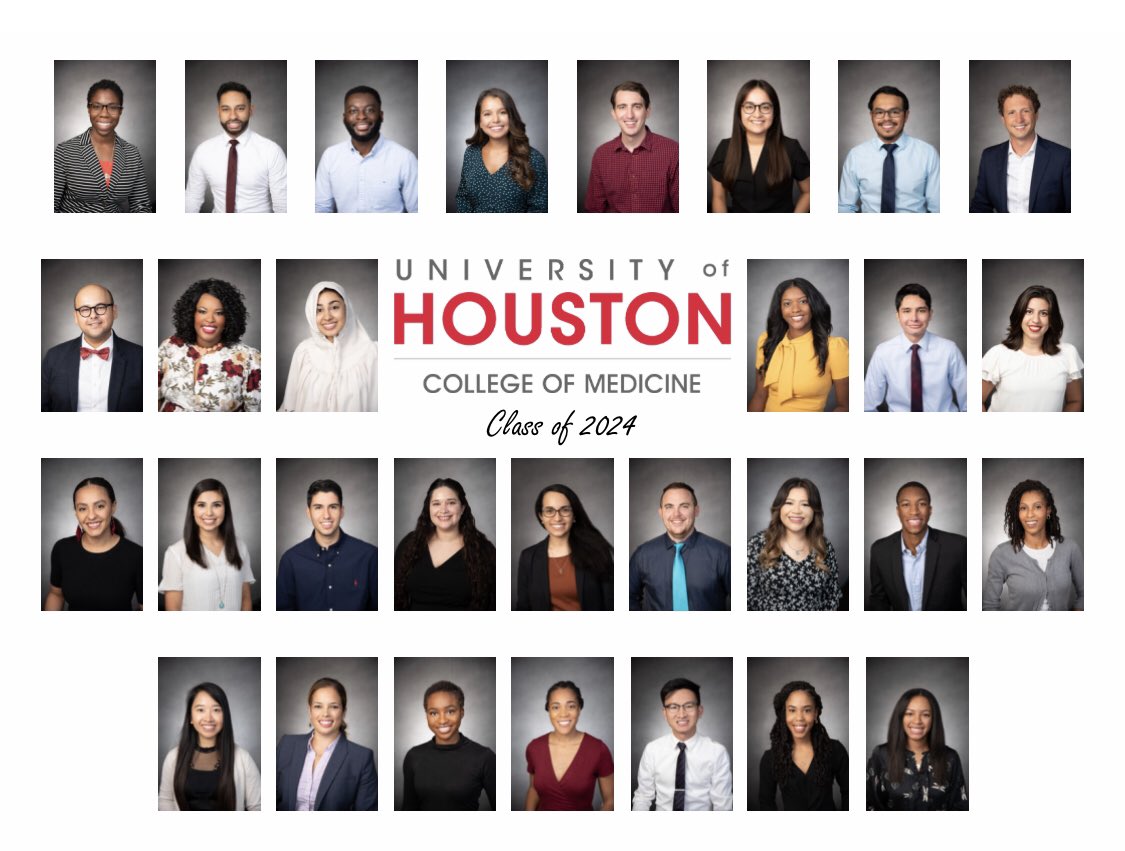

That’s the ambition shared by many of the 30 students in the inaugural class at the University of Houston’s College of Medicine. The brand new medical school aims to take a new approach to solving an old issue in Texas: a lack of primary care physicians in underserved areas.

Texas in general has a shortage of doctors, but it’s especially bad for primary care physicians.

According to the United Health Foundation, the number of primary care doctors is 29% below the national average. And Texas ranks 45th out of 50 states when it comes to access. Although access in Harris County is better than most other parts of Texas, it still lags behind the rest of the country.

“We live in a city with the greatest Medical Center in the world and yet if you look at our health statistics in certain geographic communities, we have major health disparities and significant poor health,” said Dr. Stephen Spann, the founding Dean of the UH Medical College.

Projections from the state show the shortage in East Texas is going to get worse in the next 10 years as the population continues to grow. The new medical school is one way to keep up the growing medical demand, Spann said. “Most medical schools in this country don’t emphasize primary care,” he said.

Spann said primary care is often seen as less prestigious and lucrative than a career as a specialist. UH is trying to overcome these challenges, by offering scholarships and crafting a particular culture.

“It will be absolutely against the rules for any faculty to ever say ‘you’re too smart to be a primary care doctor,'” said Spann. “That will not happen.”

In this program, providing primary care for underserved patients is baked into the curriculum.