From Texas Public Radio:

Though the census deadline has been extended to the end of October, certain areas in Texas remain undercounted — even compared to the national average.

The response rate for the 2020 census in the Rio Grande Valley is under 50% — compared to 62% nationally — and the area continues to struggle with an overwhelmed hospital system as COVID-19 cases surge in the area.

The 10-year, constitutionally mandated population count informs how much representation each state gets in Congress and the electoral college, as well as how much federal funding different cities and counties receive. That funding covers many key sectors, including education, social services, environmental protection, business development, infrasture and, critically, healthcare.

According to a 1940s film from the U.S. Census Bureau’s archives, federal funding is divided based on “unbiased facts.”

But the census has historically failed to capture the reality on the ground in the Valley.

Carlos Cardenas is the board chairman for Doctors Hospital at Renaissance in Edinburg, the seat of Hidalgo County — the most populous county in the Valley. Local officials believe in the last census, 25,000–70,000 people were not counted in Hidalgo County alone.

“In the Rio Grande Valley, it was estimated that in 2010, that we were undercounted by about 300,000 people,” he said. “The Rio Grande Valley, if it were accurately counted, could gain as much as $473 million annually — or $4.7 billion over the next 10 years — and that’s pretty significant.”

Carlos Cardenas, chairman of the board at DHR Health, stands in front of a maskeshift storage space at the Edinburg Conference Center.

The response rate in Hidalgo is about 47% — better than the rest of the Valley, but still 10 points below the state average, and 15 points below the national average.

To the east, in Willacy County, there are no hospitals for the population of about 21,000 people. EMS crews have been stretched beyond the limit by COVID-19. The nearest hospitals are in Harlingen, a half-hour drive away.

“We’re having to deal with six-to-12-hour waits at the emergency room with our patients,” said Frank Torres, the county’s emergency management coordinator.

Eleven of his 44-person staff have tested positive for COVID-19 in the past week alone, so they can’t work. Between the hour-long round trip and the hours-long wait times, the remaining EMS crews are struggling to keep up with non-COVID cases.

Torres said a call recently came in for a 4-year-old who wasn’t breathing, and every EMS vehicle was already on a call or waiting at the hospital. A supervisor was sent out and resuscitated the child, but the current situation is unsustainable.

Underfunding is a big part of this lack of resources. Willacy County’s census response rate is currently hovering around 36%.

“Whenever we apply for any federal funding, if only 40% of the population reported themselves in the census, then we’re only going to get 40% of the funding that we’re due,” Torres said. “Unfortunately, yes, it’s a very serious situation.”

But why is the response rate so low?

Officials point to the U.S. immigration system — in particular, the law enforcement component. Customs and Border Protection has additional, extra-constitutional powers when operating within 100 miles of the border, and the agency’s presence and impact is hard to miss. During Hurricane Hanna, for example, anyone without documentation who wanted to leave the area faced a tough choice.

“The Rio Grande Valley is the only region in the continental United States that has to go through an immigration status inspection point to get out of harm’s way,” Torres said. “You cannot leave the Valley without having to go through an immigration status checkpoint.”

But the fear extends beyond immigration checkpoints.

María is an unauthorized immigrant who lives in the Valley, and she asked that TPR only use her first name. She did fill out the census, she said, because she wants local schools to receive appropriate funding. According to her, rumors about deportations linked to the census are common.

“I think they’re afraid because well, with these laws — I know that it’s confidential, right, but who’s to say that they can’t suddenly deport someone and to think that, ‘Ay! What a coincidence! I just filled out the census, and look, they deported my family.’ And that’s what makes a rumor spread, you know what I mean?” she said in Spanish.

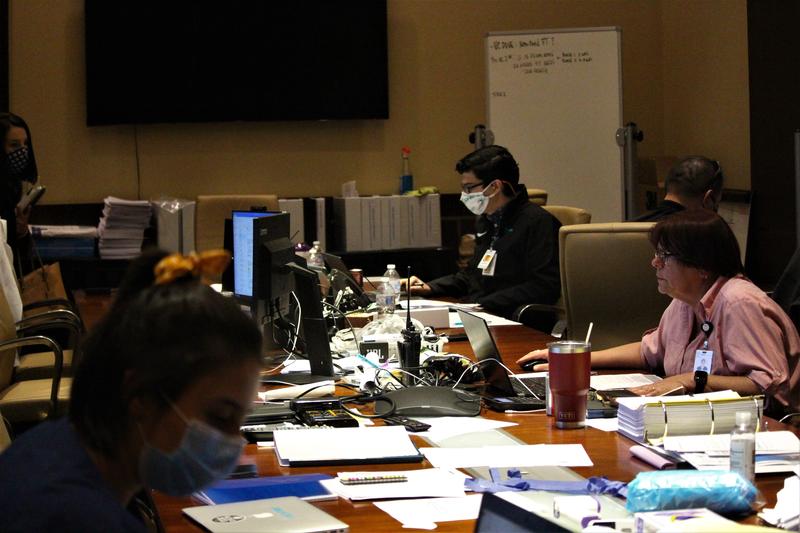

Healthcare workers enter the McAllen Medical Center for an overnight shift.

“I mean, there’s a lot of deportations, and so people are worried about deportations and being deported,” Louis Brown said. “But I think that the important thing to remember is that doing the census is totally separate from any of that, and there’s no — the data collection is confidential — 100%.”

Brown is an associate professor at University of Texas Health School of Public Health in El Paso — another region where response rates are historically low. Brown and his colleagues partner with community organizers to reach out to undercounted communities.

The reasons for the low response rates in El Paso are similar to the reasons in the Valley. Fears around deportations are first and foremost, but some unauthorized immigrants are also concerned that filling out the census will prevent them from obtaining documentation in the future.

The Trump administration’s efforts to get a since-rejected citizenship question on the 2020 census alarmed advocates, who feared it would cause an undercount. And last week, a move to exclude unauthorized immigrants from the apportionment process raised similar concerns. Altogether, the rhetoric around the census, immigration and citizenship has a chilling effect on response rates.

“Yeah, it does,” Brown said. “I think the Trump administration has done a number of actions to make this harder and to make an undercount more likely.”

Public health professionals and local officials had a lot of plans to address these fears directly: in-person events, community outreach. And then a pandemic hit.

“It’s made it harder for sure,” he said.

Phone banking and internet outreach are ongoing, but the digital divide is a big issue for colonias and rural areas, which often don’t have access to broadband or cell service. Brown and his colleagues have scheduled several community caravans, but COVID-19 makes those more difficult, too.

With the extended October deadline approaching, the Valley’s response rate is still below 50 percent, and there’s a lot of money at stake.

“I mentioned the billions of dollars that gets distributed. If you think about it on a per person basis, it works out to about $2,000 per person per year,” Brown said. “And since the census will be used over 10 years, that’s $20,000 per person that’s at stake here.”

And those figures are from pre-pandemic times. Right now, trillions of dollars are flying around. Without an accurate population count, the Valley is again being shorted on these relief bills — even though it’s one of the hardest hit areas in the country.

Michael Treviño contributed to this reporting.

Dominic Anthony Walsh can be reached at Dominic@TPR.org and on Twitter at @_DominicAnthony.