For generations of Black Texans, their stories have often been conveyed as part of a rich oral tradition that connects people to the past. But those stories, passed down through generations, have seldom been captured in print.

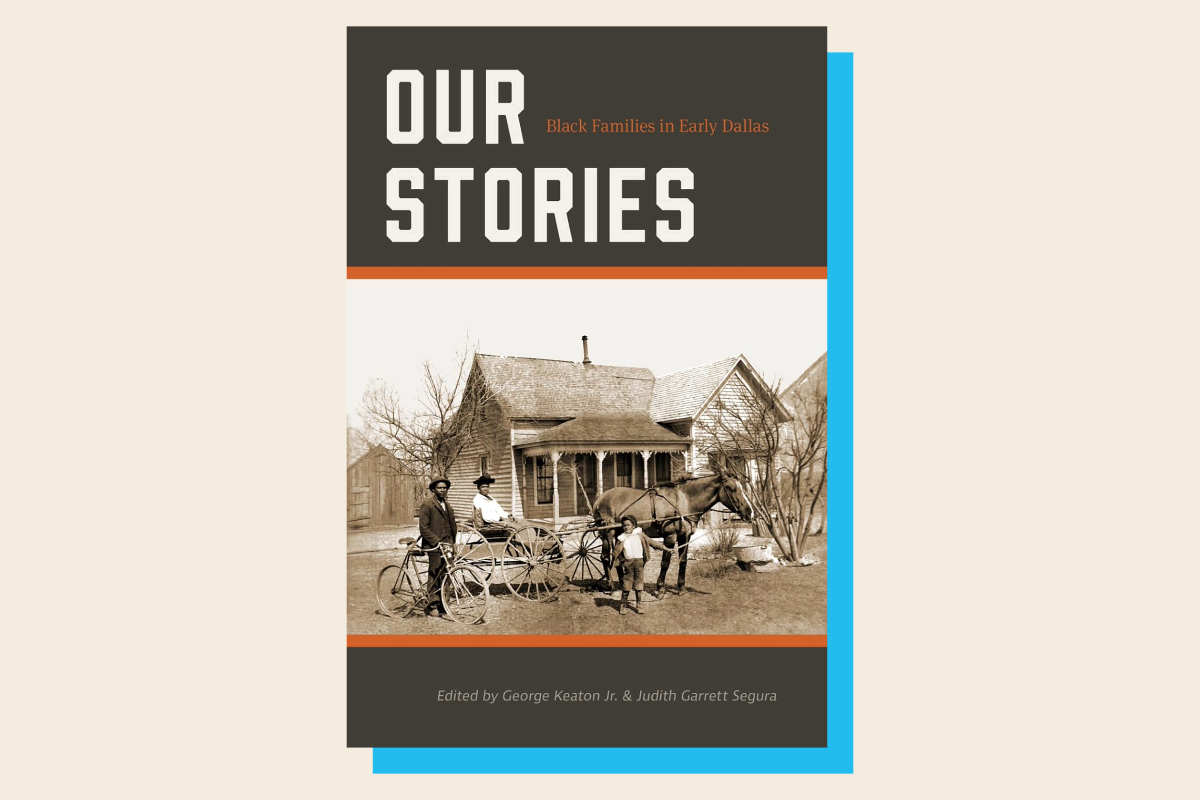

After the institution of slavery was ended, many Black families settled in Texas and began buying land to start farms, open churches and build schools. And the nonprofit organization Remembering Black Dallas has published a book that traces the history of that time: “Our Stories: Black Families in Early Dallas,” which is now out in paperback.

Remembering Black Dallas founder George Keaton Jr., who died in December, was the editor and driving force behind the book, as well as a historian and activist. His co-editor, Judith Garrett Segura, spoke to the Texas Standard about the purpose of the book and its importance in Dallas and Texas history.

This transcript has been edited lightly for clarity:

Texas Standard: Could you tell us a little bit about George Keaton Jr.?

Judith Garrett Segura: I first met George Keeton in 2019 when I was conducting research myself on early Dallas history. And he had just formed, in 2015, Remembering Black Dallas. And I learned right away that just in his head, he knew everything I needed to know.

He became my teacher, my inspiration, and he gave me what you might call a cultural education that I didn’t even know I needed. So I started working with him as a volunteer for his organization. And we ultimately decided to do this book together.

And as I understand it, he actually traced his own personal lineage to some of the first Black families to settle in Dallas, right?

That’s right. In fact, both his great-great-grandmother and great-great-grandfather had been brought to Texas as enslaved people by different farmers who were moving here. And they met each other in Dallas and formed a family. And the family’s become really well-known and very prosperous over time in Dallas, in the Black community, but not so well-known at large.

And he really wanted to be sure their story was read and wanted it in the public record, along with that of other families, a number of which had been brought here in similar circumstances as enslaved people and who in some cases were children at the time.

» GET MORE NEWS FROM AROUND THE STATE: Sign up for our weekly ‘Talk of Texas’ newsletter

How were stories collected for this book – was there a call out to families, or what exactly?

Well, there was a call out to families in 1984 by a predecessor organization called Remembering Black Dallas. And 67 stories were collected and ultimately put into little paperback catalogs to go along with exhibitions being put on during the 80s that were primarily for the descendants of those families who got copies of those little booklets.

But they never were published publicly and never made available at large. But George had copies of these books. And that’s where our inspiration came from, that we needed to make these stories part of the permanent record of Texas history.

Are there specific stories that stand out to you, maybe something that comes immediately to mind when I ask the question?

Well, several families came as enslaved children, as I said, and the one in particular who’s most well-known in Dallas at this time was Anderson Bonner, who was a child who was brought here with an enslaved widow who had inherited her husband’s travel property. And he actually grew up in Dallas. Ultimately, he became one of the largest landholders in Northeast Dallas – property that included all of what is now Medical City, Dallas, and all along the White Rock Trail, the White Rock Creek in Northwest Dallas.

He was a brilliant businessman who never learned to read. So all of his deeds, of which there are a great many, and all of his property contracts and documents are signed with his X. But he really he was brilliant. And his descendants are still very much involved in Dallas life and recently gathered to honor him at Anderson Bonner Park in Dallas.

You make a note that even though there is acknowledgment of the hardships and the atrocities that many of these settlers in Dallas face that the storytellers in this book focus on the triumphs over adversity and successes achieved against the odds. Could you say more about that?

Yes. The most touching thing about reading these stories is that they record how a family with 19 children sent all of them to college, for example. Or another family where all of the children became schoolteachers. Or others where generations of lawyers grew out of this family. And these are the stories that in particular, those of us who are white people don’t know. We don’t know about the early tryouts because those things were never published.

But this is a book of such cultural enlightenment that my aim – and George and I were open about this – is to make this available for white readers who have no idea about how rich this culture was and whose understanding of our culture in Texas in particular – because these are all Texas stories – is going to change. It changes your heart, you know, to read these.

I was going to say, I bet you when you drive around Dallas now, you see this city in a completely different way.

Absolutely. And I have a map in the book which shows where the main communities were. And at some of the readings that I’ve done, people in the audience say, “oh, my God, I had no idea. I live on that street,” you know, about Turner Way, for example, and other names that they just had no connections about why their street was named what it was. And so I’m confident it’s opening hearts of a lot of people who don’t consider Black history of interest to them.

And I’ve been concerned from the very beginning that my representing the book without George beside me – we only had a chance to do one book talk – that I’m not viewed as appropriating somebody else’s story, you know? And George had no problem with my being his 100% partner in this. As I said, we became just best friends. But he died within months, actually within weeks, of the diagnosis, and after only one book talk. And so I’ve been careful in treading lightly and mostly just trying to make it clear that my aim is to educate my race about George’s race.