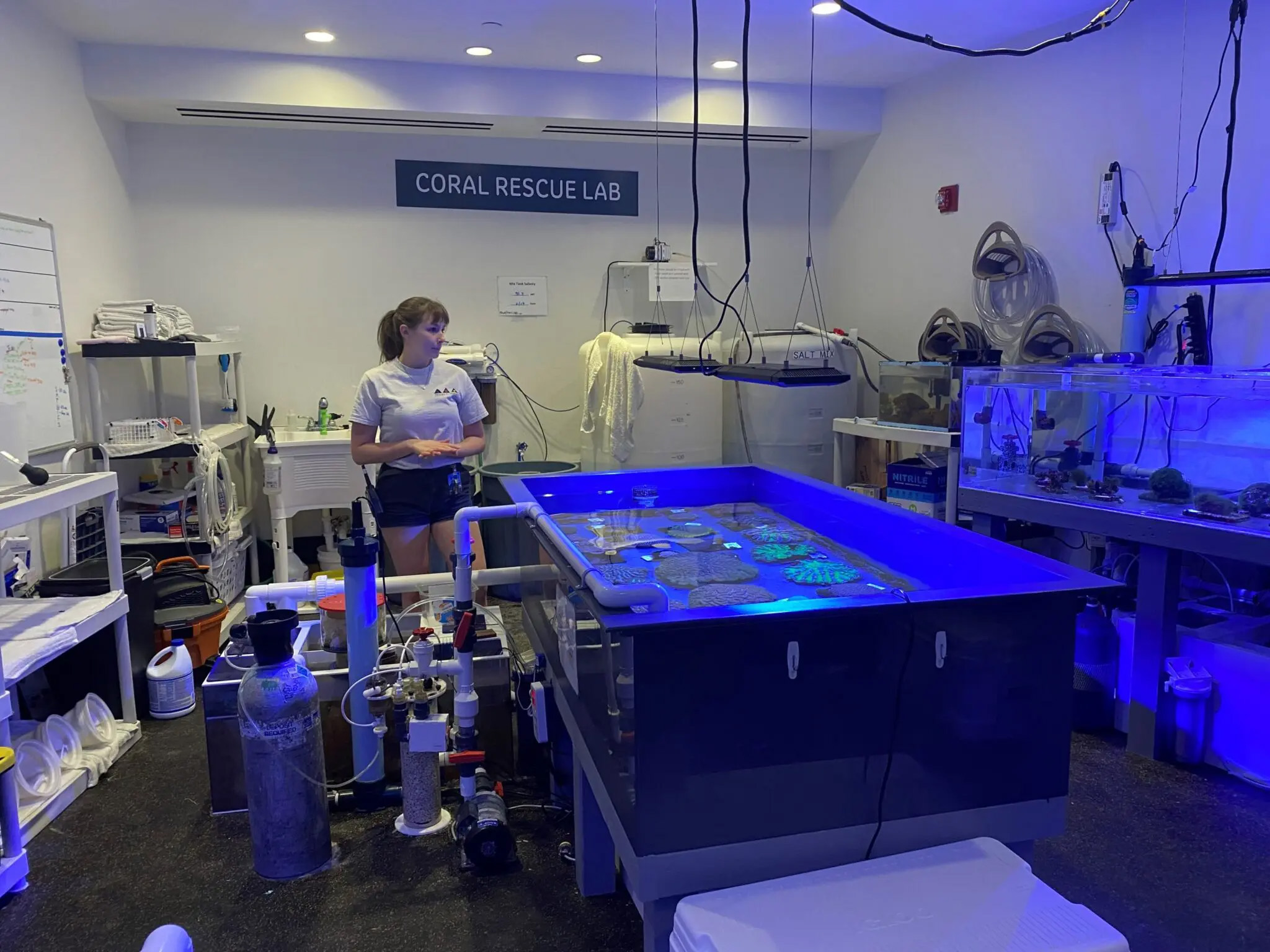

At the Moody Gardens aquarium in Galveston, around 100 different corals sit in water tanks in an enclosed room. Some are brown with markings that make them look like brains. Others have bright green coloring in between their grooves. All were rescued from Florida after a deadly coral disease, known as stony coral tissue loss disease, started infecting reefs there.

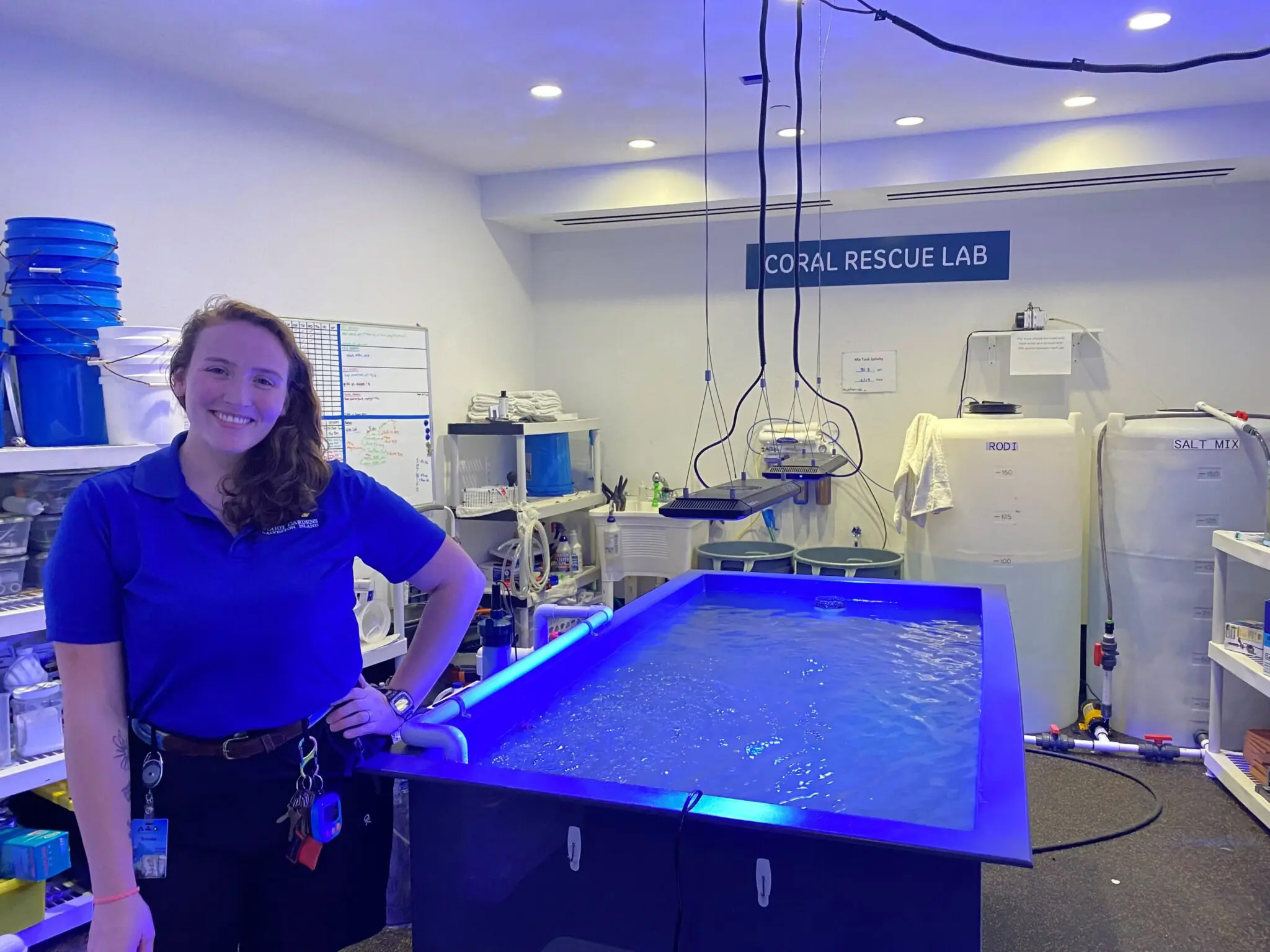

“There’s not exactly a book about how to take care of a coral, and a lot of these species have never been taken care of in captivity prior to this program,” said Brooke Carlson, a senior biologist at Moody Gardens.

Moody Gardens is one of around 20 zoos and aquariums across the country that took in rescue corals from Florida back in 2019, with the goal of raising them in captivity and eventually breeding them to restore damaged reefs.

“The plan was to take as many healthy corals out of the population as possible and put them in captivity so that they were safe from the disease,” said Carlson.

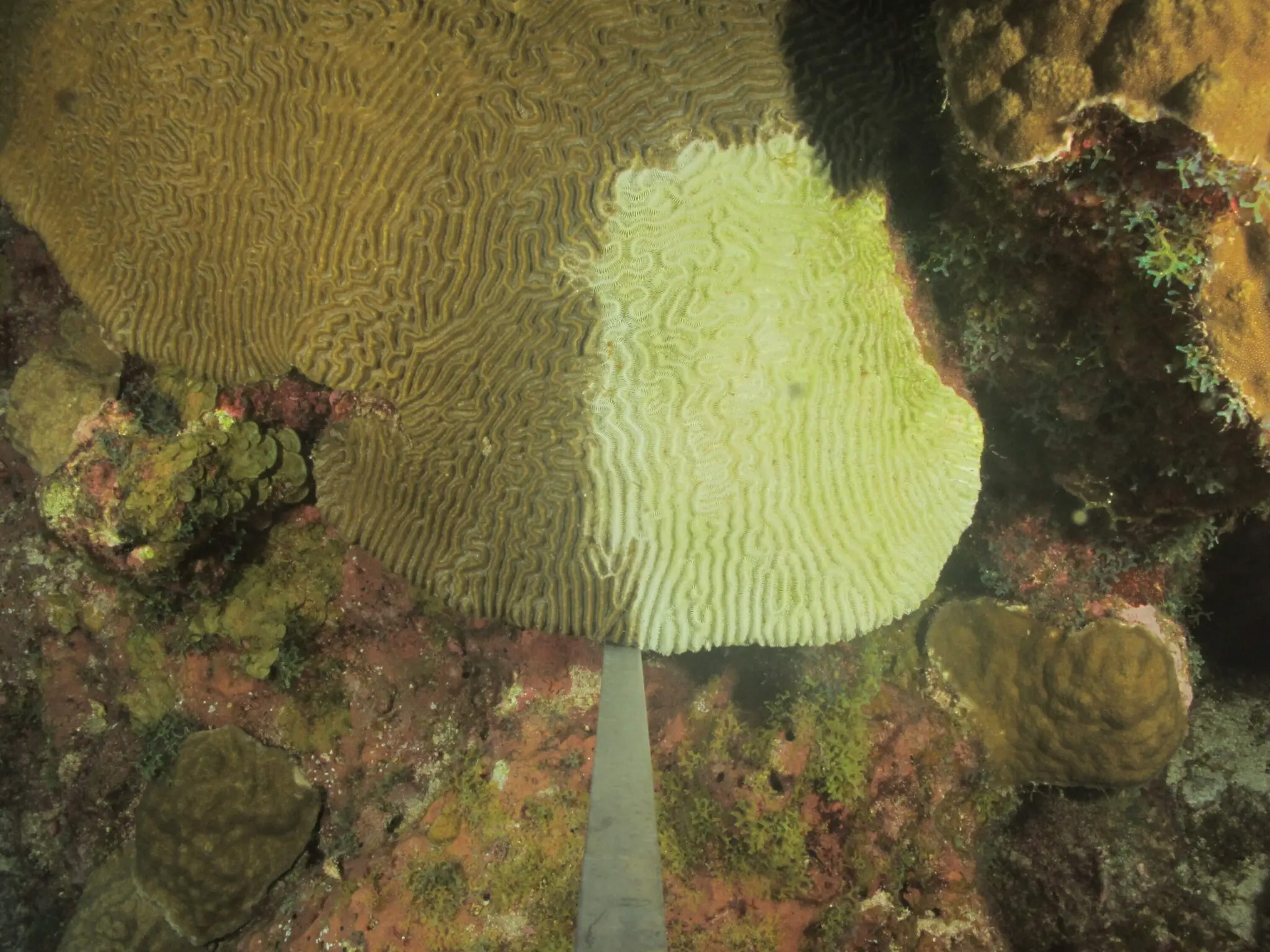

First detected in Florida in 2014, stony coral tissue loss disease is characterized by how quickly it spreads and its high mortality rate. Once infected, corals typically die within weeks to months. Wildlife officials are racing to protect the corals and prevent the disease from spreading further.

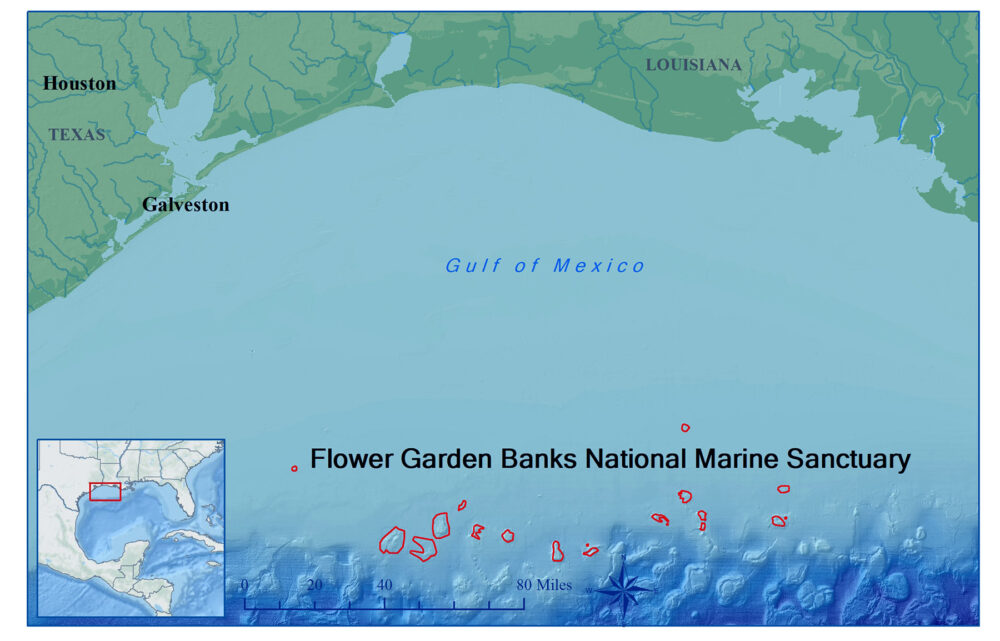

Since it was first discovered in Florida, stony coral tissue loss disease has spread to more than 20 Caribbean countries and territories. Now, divers have noticed potential signs of the disease at the Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary, a protected area some 100 miles off the coast of Galveston.