When it comes to biographies, there are perhaps no authors more influential than Robert Caro.

In 1974, after seven years of research, Caro released his first book, “The Power Broker” – a 1,100-page biography of New York City urban planner Robert Moses. After that, Caro turned his attention toward a subject more familiar to Texans: Lyndon Johnson.

Sean Saldana / Texas Standard

Currently sitting at four volumes and more than 3,000 pages, Caro has spent the last five decades documenting the 36th president’s rise from a poor boy growing up in the Texas Hill Country to eventually signing the 1964 Civil Rights Act and extending the war in Vietnam.

In his career, Caro has won two Pulitzer Prizes and three National Book Awards, but he doesn’t do it all alone. In his equally long and illustrious career, Caro’s editor, Robert Gottlieb, has edited hundreds of books written by the likes of Toni Morrison and Joseph Heller.

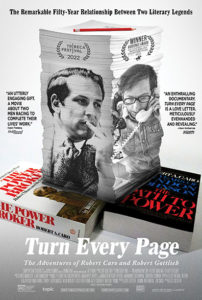

In the publishing world, the relationship between Caro and Gottlieb has become legendary. It’s also the subject of a new documentary directed by Gottlieb’s daughter, Lizzie Gottlieb, who joined the Texas Standard to talk about the documentary. Listen to the story above or read the transcript below.

This transcript has been edited lightly for clarity:

Texas Standard: Let’s talk about the title of the new film.

Lizzie Gottlieb: So, “turn every page” is the advice that Robert Caro was given when he was a young reporter at Newsday in New York. His boss gave him this piece of advice. He said, “when you’re doing research, turn every page, kid.” He said, “turn every damn page.” And Bob Caro has taken that to heart in his research of doing absolutely everything to uncover the truth of what has happened in American politics. And I thought it also kind of represents my father’s work. He’s edited something like 700 books, and they’re both unbelievably industrious and diligent. And so it felt like the right title for this movie.

Courtesy of Sony Pictures Classics

I think it’s safe to say that most people are not very familiar with the relationship between Robert Caro and your father. Whereas for you –

I mean, it’s part of the air I breathe. My father ran Simon & Schuster, and then Knopf, then the editor of The New Yorker. So I grew up in this house surrounded by writers.

This must have been somewhat cathartic then, to go down this path.

Well, interestingly, of all his writers, so many of them were close family friends. And in all those years, I never met Robert Caro.

So there was something strange and different about their relationship. They’ve been working together since 1970, and they’re still at it. They’re trying. They’re in a kind of race against time to finish their life’s work together. And I was really interested in the creative alchemy that happens between these two people. As you say, people don’t really know how books get made. They don’t really know that process, even if you’re a reader. I was in the unique position to be able to bring people into this secretive world, an unusual process, and this quite thorny and very productive relationship.

I love how you characterized it just then, and I love the way that you use the word “alchemy.” As far as I know, they have not allowed anyone to actually visibly witness that editing process. How did you convince them to let a camera in on that?

Well, that’s a good question. They both were absolutely against it.

It’s like the Supreme Court: there shall be no cameras here. There’s this almost sacredness, it seems to me.

That’s exactly right. And, you know, also, my father says nobody should know what an editor does because an editor’s work should disappear. And his joke is, nobody wants to hear an editor say “and then I said to him, ‘Leo, don’t just do war. Do peace, too.’” It’s only showing off, right? So there is something sort of sacred and private and secret about what goes on between a writer and editor. But my dad says he can never say “no” to me. So I kind of took advantage of that and just pushed and pushed. And finally he said, “Well, you can talk to Bob Caro, but he’ll say ‘no.’” And then I had this long process of trying to convince Bob Caro to trust me. This man who spent his life trying to get other people’s stories out of them. I think he was aware that I was trying to convince him to collaborate with me, and he eventually did.

And so upon witnessing this, what was your feeling?

I mean, taking this in was an incredible, privileged feeling to be able to spend this time. It took me seven years to make this movie and to be able to learn about – they’re both so industrious and they’re so adorable and they’re so dedicated to what it is that they do. And they care about every element. So they care about, you know, uncovering the truth about how Lyndon Johnson stole the Senate election of 1948. But they also care as deeply about punctuation. You know, they have had screaming fights apparently for five decades. And you say, “what do you fight about?” And they say, “we have very different feelings about the semicolon.”