From KERA News:

Frances Rizo had a newborn and a young son when 12-year-old Santos Rodriguez was shot and killed by a Dallas police officer. What happened on July 24, 1973 struck fear in her.

“It was actual shock. It was as if I had been in the room or witnessed it,” Rizo said. “It was just such a graphic thing.”

Officer Darrell Cain and his partner had taken Santos and his brother, David, from their home that morning after responding to a call about a burglary at a local gas station.

The brothers were still in their pajamas when they were handcuffed and placed in a police car. According to testimony from David, Cain had taken his revolver and spun the cylinder. He questioned Santos about the burglary and aimed the gun at his head. Santos denied any involvement and Cain fired. Santos was killed as his brother sat in the backseat.

The tragedy hit too close to home for Rizo.

“I just couldn’t believe it,” she said. “My oldest son was 10 1/2 at the time that this happened and I immediately imagined that this could have happened to me and my kids.”

On the 50th anniversary, Dallas residents are remembering Santos Rodriguez and reflecting on police-community relations today. Events were held over the weekend. People turned out for a march on Sunday and other events are planned this week.

Rizo was on Dallas’ Community Relations Commission at the time. She said she often helped translate for Spanish-speaking residents who attended meetings. She remembers what had happened to Santos.

“I couldn’t hold it in and I started crying,” she said. “Even right now, I’m getting goosebumps and emotional because that has never gone away.”

Santos’ murder sparked protests and meetings between the Mexican American community and city leaders and the police chief.

Sol Villasana, a Dallas civil attorney, was a college student at SMU then. He participated in some of those events and was moved by the push for justice.

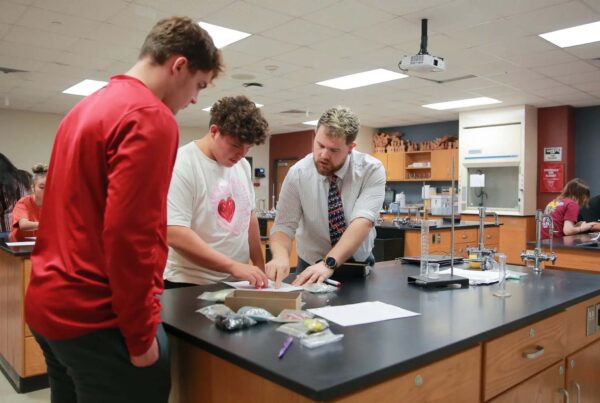

Sol Villasana before a press conference regarding events planned for the 50th anniversary of the death of Santos Rodriguez on Tuesday, July 18, 2023, at the African American Museum of Dallas. Villasana was a college student when Santos was killed by a Dallas police officer.

Yfat Yossifor / KERA News

“It was a shift in the earth’s plates,” Villasana said. “There was a legacy of police violence against Latinos,” he said. “This was so tragic and egregious that it was like the community was not going to take it anymore.”

Villasana said he’d never seen the Latino community rise up against police violence before.

Cain stood trial and was convicted of murder with malice. He was sentenced to five years in prison but ended up serving only two and a half years before being released.

Hadi Jawad, a community leader who’s been organizing events marking the 50th anniversary, said there’s still an open wound in the city, especially for the family. Santos’ murder took a toll on his brother and mother Bessie Rodriguez.

“She got no help, no financial help. The mental emotional help,” Jawad said. The brother David is traumatized. He still suffers. He got no help.”

The tragic events did, however, mark a turning point, not only protests but also new leadership, Jawad said.

“We got more Latino police officers on the police force,” he said. “Latinos became politicians. Things began to change. But we look at 50 years later, we still have a long way to go.”

Jawad has been working closely with Rick Halperin, director of SMU’s Human Rights Program. Halperin was a grad student at SMU in 1973. The killing and its aftermath also deeply affected him.

When he returned to SMU in 1985 to teach human rights, Halperin decided to ask his students what he felt was an important question.

“I ask my classes all the time, ‘How many of you are from Dallas? How many of you have heard of this terrible crime?’ Almost nobody,” Halperin said. “It’s mind boggling how students can come through DISD (Dallas Independent School District), private school, public schools, all parts of the city…and nobody’s heard of this.”