In August 1969, Henry Kissinger met in secret to try and end the Vietnam War. Hurricane Camille struck the Mississippi coast, killing over 250 people. The Manson family went on a murderous rampage through Los Angeles. And amid the turmoil, Billy Kirby was just kind of hanging out.

Kirby had just graduated from high school – one of 13 members of his senior class in Scurry, a small community in Kaufman County, Texas. He didn’t have a job, so he spent much of his time playing music with his best friend, Stanley Jones.

“We did play a couple of what we’d call sock hops,” Kirby says. “We’d get like $2 or $3, $5 apiece. Which was a lot of money when you paid 16 cents for a gallon of gas.”

Kirby and Jones wanted to go to Woodstock, but they heard about it too late to get there. As luck would have it, there was another giant festival planned for just two weeks after the New York festival. And this one was much closer to home – the Texas International Pop Festival, held just an hour west of Scurry, in a town called Lewisville.

Today, over 100,000 people live in Lewisville. The 25 miles of I-35 that stretch between the town and Dallas is now completely developed. But back in 1969, it was a small, rural outpost – home to less than 9,000 people.

Lewisville is not exactly the kind of place you’d expect to find a massive music festival featuring some of the most iconic acts of a generation. I would know – I’m from there. Our claims to fame are few. The 1996 Lewisville Fighting Farmer football team got its photo on a Cheerio’s box after winning the state title game without throwing a pass. At the annual Western Days celebration, we host the World Tamale Eating Championship. That’s about it.

It’s a bedroom community – a pleasant suburb now, a quiet, country town in 1969. But that was just fine for Angus Wynne, one of the festival’s organizers. Wynne ran a concert company out of Dallas called ShowCo, and he partnered with some other promoters from Atlanta to develop the Texas International Pop Festival. The choice of a site in Lewisville only came after a lengthy search.

“We just went out and got away from town as much as we could and started looking for places on major highways,” Wynne says. “I mean we went through corn fields, trash dumps, we went through everything looking for a piece of rentable property that was in good shape.”

The place that fit the bill was a racetrack called the Dallas International Motor Speedway, located at the south end of Lewisville. There wasn’t a lot of shade, but the infield had plenty of grass for concertgoers, and people would tolerate the heat if the lineup didn’t disappoint.

And, it didn’t.

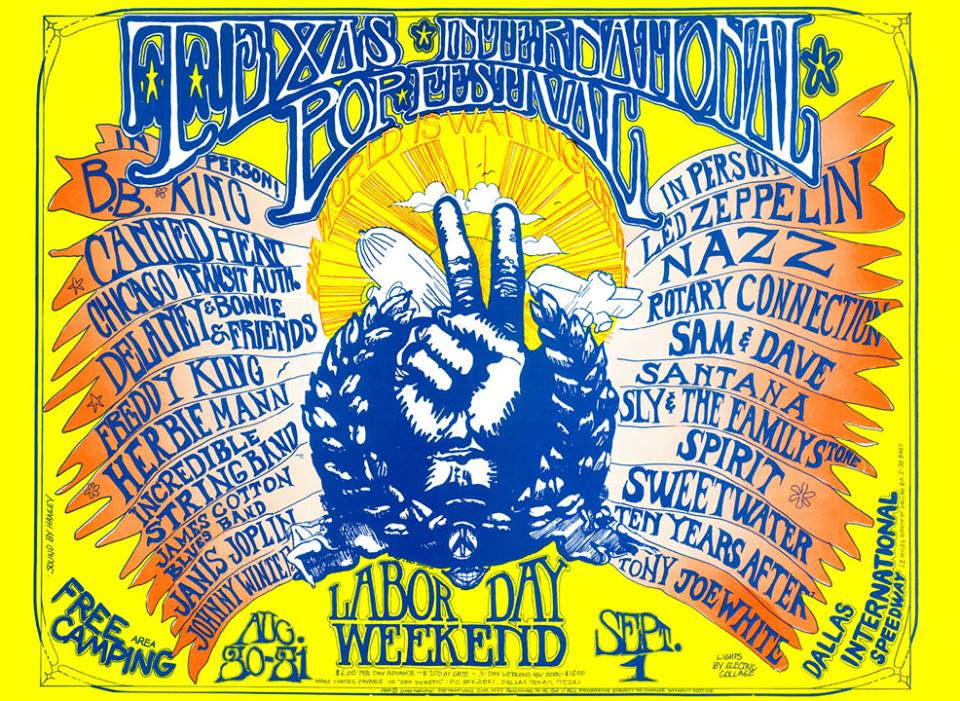

Wynne and his partners booked over 20 bands to play over the three days. The lineup included B.B. King, Santana, Chicago, Rotary Connection, Herbie Mann, Sly and the Family Stone, Janis Joplin and Johnny Winter. The most expensive act to book was an up-and-coming British band called Led Zeppelin. They were just about to release their second album.

The lineup generated excitement among would-be concertgoers. But in Lewisville, the reaction among residents looked more like preparing for a natural disaster.

“I don’t think anybody anticipated even knowing what it might be or turn out to be,” says Johnny Sartain, Lewisville’s city manager at the time.

The festival was expected to draw at least 100,000 people over three days, stoking fears among some North Texans of unwashed hippies, biker gangs and general chaos.

“It’s kind of [dramatic], but some of the ladies were ‘I’m scared to go to the grocery store, I’m scared to go downtown.’ This was a quiet little country town and the people that saw it, they were just shocked,” says Johnny Surtain’s wife, Tommye.

The concern may sound hyperbolic now, but it didn’t feel like an exaggerated response back then. Doomsday seemed to be coming, so Sartain prepared accordingly. Before the festival, he went to a local gun shop called Dave’s House of Guns, and bought several Thompson submachine guns – the kind you might see in an old gangster movie.

“We were five or six people and that was it,” Sartain says. “We didn’t know what violence might come about from it or if there was any.”