From Texas Public Radio:

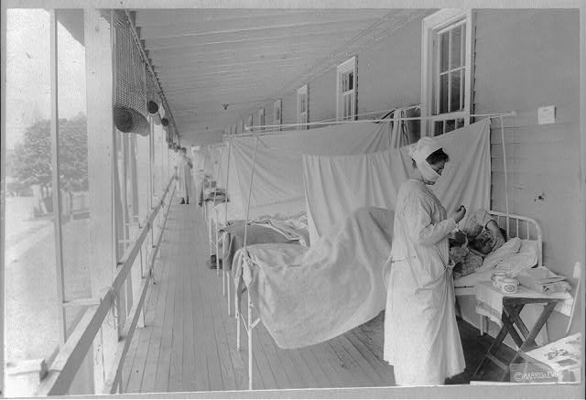

It’s been called the mother of all pandemics: Spanish flu.

It roared around the globe in late 1918, infecting a third of the world’s population and killing 51 million. The modern, thriving city of San Antonio essentially shut down — twice — as the flu took its toll.

Louie Edward Mayberry moved to San Antonio in 1918. He was 11 years old. Reflecting on the move, he said, “I started school, and just a few days they had a flu epidemic in San Antonio and they turned the schools out.”

Mayberry’s oral memoirs were recorded in 1987 and are archived at the Baylor Institute of Oral History. At the time of the recordings, Mayberry still remembered clearly the time the city stopped everything as the flu ravaged its residents. Mayberry shared how the city closed schools and other gathering places in mid-October, then declared the epidemic over the day World War I ended.

“Then school started again,” he said. “It went on for a couple of weeks and then it turned out again. We didn’t get much schooling before Christmas.”

The first time the Spanish flu hit San Antonio, it sneaked up on the city. Most Americans during the fall of 1918 was the war. But beginning in late August and early September of that year, soldiers fighting in Europe were focused on a flu that was sickening troops from all over the world.

Then, troops in the U.S. started getting sick, including those at San Antonio’s Camp Travis, home of the Army’s 19th Division.

Ana Martinez-Catsam who teaches history at The University of Texas of the Permian Basin, is from San Antonio and wrote an article for the Southwestern Historical Quarterly called “Desolate Streets: The Spanish Influenza in San Antonio.”

“Between Sept. 19 and 20 there were flu-like cases in Camp Travis, and so doctors reported this as the flu,” Martinez-Catsam says. “Of course, rumors start to spread that it’s influenza and military officials want to reassure the city that it wasn’t.”

But it was, and by the time the military acknowledged it, Martinez-Catsam says it was all around.

“Travis was hit, Fort Sam Houston, Kelly, so it was at the military bases. And it’s on Oct. 1 when the military pretty much quarantined the military installations. Enlisted men could not visit San Antonio,” Martinez-Catsam says.

San Antonio’s city health officer Dr. William Anthony King had been paying attention to what had been going on at the military installations, she says, but he wasn’t convinced it was a big deal, and he didn’t think his city was at risk of an epidemic.

“San Antonio was known as a health destination — had a clean-up campaign; a few mild cases of the flu — but he didn’t think it would be severely hit by the influenza. If anything, they could limit it,”Martinez-Catsam says.

However, by the time King and the Board of Public Health decided on Oct. 16, 1918 to close the schools, churches, lodges, theaters, and to ban public gatherings, the epidemic was already reaching its peak.

Three days later, doctors reported a total of 700 new influenza cases in one day.

And people were dying.

“You have a number of children who pass away within the same family. You have a mother and a father. You have a mother and a child,” Martinez-Catsam says. “So what would happen, because it was so highly contagious, several members got sick and several members passed away.”