From The Texas Newsroom:

In the fall of 2017, Fort Bend Independent School District broke ground on a new career and technical center in Sugar Land, Texas. As the district superintendent gestured to the empty field behind him, he called the future school “an enormous step forward,” and said it would be “preparing students for generations and generations.”

But before launching Fort Bend into the future, the new school unearthed evidence of the area’s dark past. Just a few months into construction, a backhoe operator was filling in a trench when he spotted a bone.

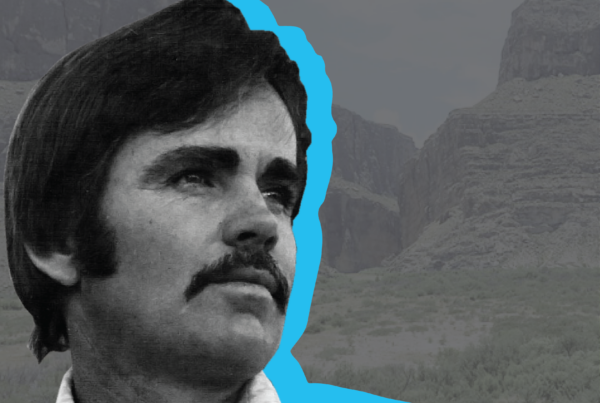

Reginald Moore spent years pushing the City of Sugar Land to acknowledge its not-so-sweet origins.

Courtesy Of Marilyn Moore

“They’d been seeing agricultural remains and things like cow bones and horse bones and sheep and pig and all that–they’d been seeing that the whole time. But there was something a little different about these bones,” said Reign Clark, the archeologist who led research on the site.

They were different: They were human remains. Day after day, more were unearthed. Each grave was draped with a plastic tarp, and soon the whole field was covered. By the end of the summer of 2018, a total of 95 bodies had been found.

Everyone started asking the same question, one that remains unanswered all these years later: Who was buried here?

One local man claimed to know the answer, and had been warning anyone who’d listen about it for years. His name was Reginald Moore.

Moore was impossible to miss. He was 6’2 with a booming voice and the cadence of a preacher. Moore had become a regular fixture at city council, school board and county commissioners meetings, where he pushed the City of Sugar Land to acknowledge its not-so-sweet origins.

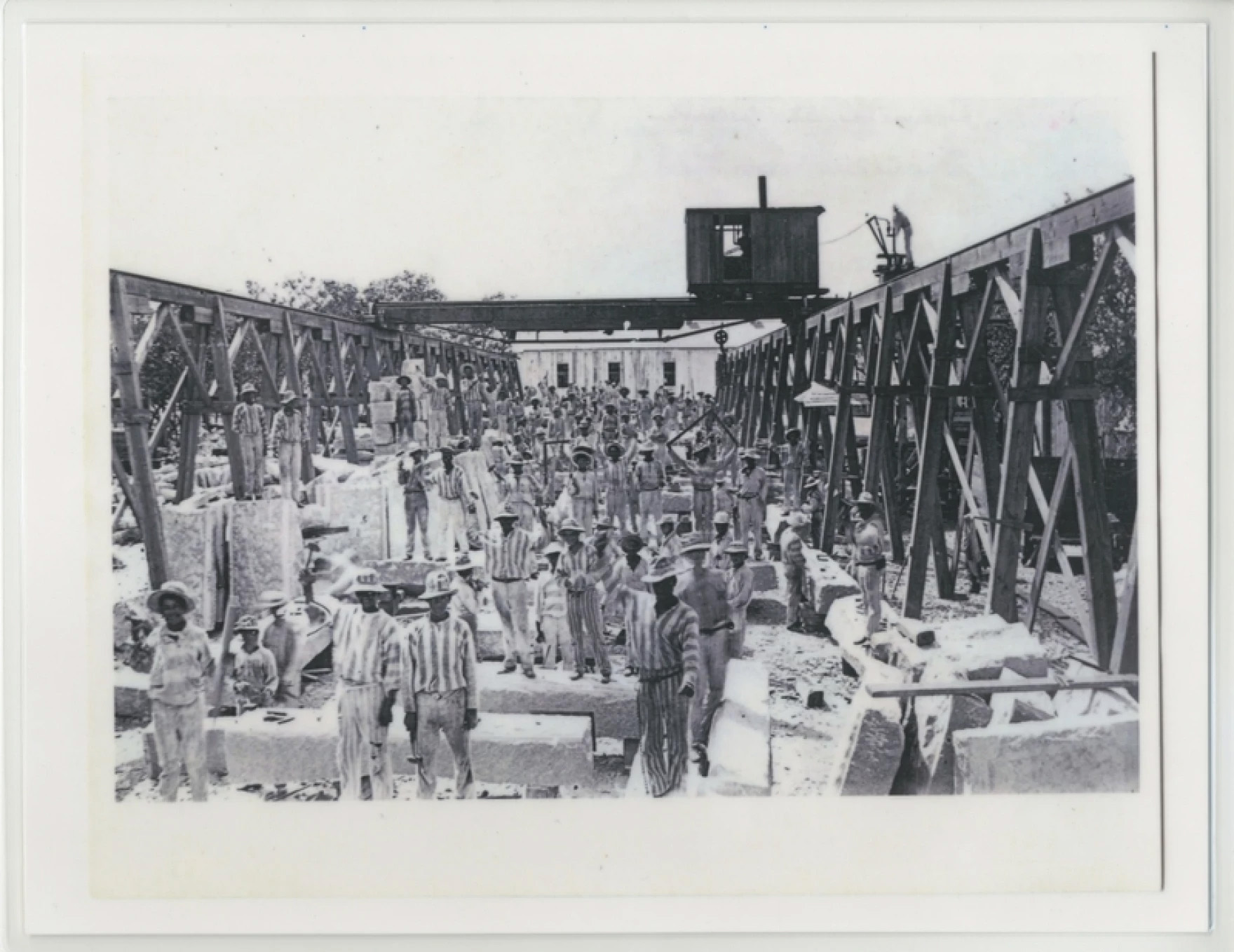

Unearthing a history of convict leasing

Today, Sugar Land is one of many desirable suburbs on the outskirts of Houston. But in the early 1800s, it was home to some of the hottest real estate in Texas. When the “Father of Texas” himself – Stephen F. Austin – was doling out land to the state’s earliest non-Native settlers, he chose the area for his homestead. The City of Sugar Land is proud of this heritage, honoring it with landmarks like First Colony Mall, a neighborhood called New Territory, and Settlers Way Park.

A less discussed part of its history: Near the turn of the 20th century, the area was the largest hub for convict leasing in Texas. The practice of leasing convicts for labor was adopted across the South in the decades following the Civil War. At the time, it solved two major issues white landowners faced: It provided a cheap workforce to replace the slaves they’d lost and allowed them to continue treating Black people as second-class citizens.