This article was originally published by the Texas Observer, a nonprofit investigative news outlet. Sign up for their weekly newsletter, or follow them on Facebook and Twitter.

When Philip Souza gets ready to work in his unusual island-based recording studio, he activates an “On Air” sign to warn others to be quiet. Unlike most recording studios, however, his sign sits in a bookcase, sandwiched between shelves of ethanol-filled jars containing preserved crabs, shrimp, and fish.

On the table where a microphone would normally be, there is a box-like shape made of undulating black soundproofing foam. Under the foam, Souza places an aquarium containing fish from the downstairs wet lab, and pokes an omnidirectional hydrophone–a waterproof microphone–into the water.

“This is our small fish recording studio,” explains Souza, a Ph.D. student at the University of Texas Marine Science Institute in Port Aransas. “The acoustic foam is keeping out enough of the background noise where you can actually make out those vocalizations from the really small animals.”

It’s here he’s trying to record the sounds of cryptobenthic fish, bottom dwellers tinier than a pinkie finger. “A rule of thumb is that the bigger the sound-producing organ in the animal, the louder the sound is. So with these little tiny animals, because their bodies are so small, their sound-producing organs are also very small, so it really does take some very sensitive equipment in order to capture that,” he says. This project is in its beginning stages. Souza and his advisor, Simon Brandl, theorize that these diminutive fish are a chatty bunch that make noise on oyster reefs but are trying to confirm exactly what sounds they make by recording them in a laboratory setting.

Souza’s recordings don’t make the radio or online playlists. But, when he finishes his Ph.D. in the fall of 2024, the fish sounds he records in Texas will be stored on websites like FishSounds, a repository of fish vocalizations worldwide, and Discovery of Sounds in the Sea, which stores recordings of all sea life.

The hope is that “we can continue to add to the global library of fish sounds by recording some of these less studied animals here,” Souza said. “And that way, well into the future, researchers can use these sounds to monitor the diversity of fish in their environment.”

Souza grew up near the ocean in Massachusetts, but he spent summers on the Bahamian island of Exuma, where his grandmother lived. “I spent the majority of that time in the water from a very young age. I’d spearfish and snorkel and got scuba certified when I was 16,” he said. “Most of my life, I knew that I wanted to be a marine biologist.” He fell in love with fish sounds the first time he heard them with UT’s equipment in the first year of his Ph.D. program.

His childhood interest became grounded in science through marine biology classes at Whitman-Hanson Regional High School taught by Courtney Jones, a biologist who worked on whale-watching boats and at the New England Aquarium. “I’m really, really proud of Phil,” she said. “When I think about retiring, which I’m thinking about a lot, I remember kids like Phil. That’s why I get up in the morning.”

Souza studied marine science at Boston University and then earned a master’s degree from the University of Miami, where he studied queen conch in the Bahamas. He hopes one day to return to New England to research talkative fish there, like cod and haddock, taking with him the knowledge he’s acquired in Texas.

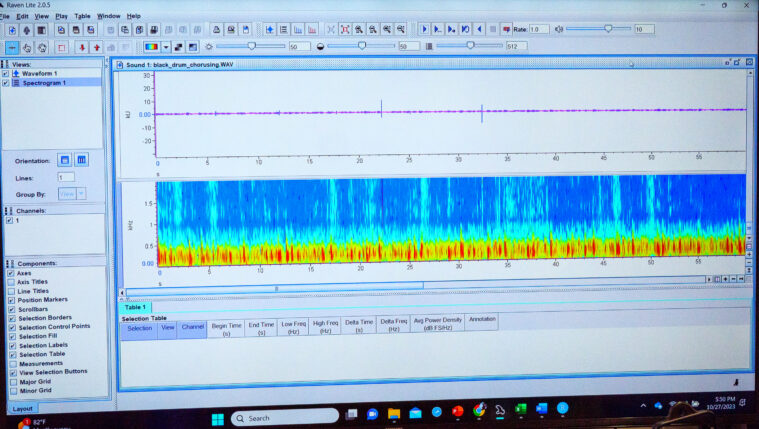

He stores more recording equipment in a lab at the institute in the fishing town of Port Aransas on Mustang Island. In this room is a rack of wetsuits, a TV screen, a table, and lab equipment. He sits down at the table and pops open an audio file on his computer. A spectrogram, a visual representation of sound frequencies, activates and odd noises emanate from its speakers: “Creeaaaak. Thump…. thump…thump. Rat-a-tat-a-tat-a-tat.”

The sounds of fish that live in the nearby Mission-Aransas Estuary fill the room: red drum; black drum; spotted sea trout; silver perch; and Gulf toadfish.

Souza has learned to tell these fish apart by the sound signature on the spectrogram; by the cadence, duration and frequencies of the fish sounds; and by the time of day or season it is when the fish vocalize. “The Gulf toadfish is my favorite fish here. Isn’t it adorable?” Souza said, pointing to a photo on the screen. The fish is well-named, with a big mouth and lumps and bumps on it. Its vocalization, which sounds like a goatherd blowing a horn in the Alps, is, indeed, adorable.

Fish make noise to communicate stress; to defend territory; and during courtship and spawning when they’re trying to hook up with a mate, he explains. The estuary is noisier in the spring during spawning season and at dusk and dawn when fish often aggregate and “chorus.”

“Earlier in the evening, when they’re first getting started, it’s a lot easier to hear and to make out the individual calls because they do sort of ramp up,” Souza said. “There’ll be a few individuals that will start and then all their friends will join in, and then this is when you get the chorus thing.”

Some species vocalize all day, including the Gulf toadfish. “During their nesting and spawning season, you can hear those really adorable calls throughout the entire day, which is a joy. That’s something that I’ll never complain about—being able to hear those all day long.”

Recently, Souza has been focusing his attention on the soundscape around oyster reefs.

Some marine scientists have already found that if they play recordings of a healthy reef on an unhealthy coral or oyster reef, it speeds up the colonization of the reef. Fish and other reef dwellers, apparently, want to hang out around a reef with a healthy soundscape.

Souza is trying to determine whether the diversity of sound, known as its acoustic complexity index, and the volume of these spontaneous fish symphonies around oyster reefs in the estuary are good indicators of the health of a reef ecosystem after it’s been disturbed or restored.

To do this, he sets out oyster sampling trays (plastic milk crates lined with mosquito netting and partially filled with oyster shells) on oyster reefs in the estuary to measure how many animals colonize the artificial reef over a three- to four-week period. “When we pull them, we find all of these little animals inside. And it gives us a snapshot of what the community looks like on those oyster reefs at that time,” Souza said. “We count, measure, and identify all of these species, and then compare what [animals] we’re finding in these trays to what we’re hearing with our acoustic recorders at those reef sites.”

Besides studying fish sounds around oyster reefs, Souza also has teamed up with scientists from the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department (TPWD) to study and record fish in the Mission-Aransas Estuary, a system of bays that is about a 15-minute drive north of the Marine Science Institute.

Twice a year, in the spring and fall, TPWD sets out gillnets that are 600 feet long and 6 feet high. One side is anchored near the shore and the other side is in water that’s usually less than 20 feet deep. Each 100-foot section of the net has different sized holes so it can trap a range of fish sizes. When fish swim into the net, their gills get caught. The nets are deployed at dusk and, when they’re picked up the next morning, scientists count how many fish of each species were caught.

“The gillnet studies have been used for nearly 50 years to help make decisions about whether we need to make regulatory changes if we see certain populations dwindling,” said Zachary Olsen, the Aransas Bay Ecosystem Leader for TPWD.

But sound studies are relatively new. Scientists have used passive acoustic monitoring, called PAM, for about 20 years.

Operating together from a boat, TPWD deployed a gillnet then Souza anchored his recording equipment, encased in a waterproof tube, next to it. When Souza retrieved the recorder 24 hours later, he analyzed which fish vocalized on the recording. Then he, Olsen, and Brandl, Souza’s Ph.D. advisor, compared the fish in the recordings to those caught in the gillnets.

One finding, after 51 samplings during two springs and two falls, was that about half of the fish in the estuary are sound producers. “That just goes to show how important sound production is in our local estuaries,” Souza said.

A second finding was that the volume of sounds correlated with how many fish TPWD caught. “[The recording devices] did a good job of capturing the abundance of fish and the presence or absence of certain species of fish. So the more abundant the fish were in the area, the louder the soundscape was,” Olsen said. The loudest fish on the recordings were those in the sciaenid family, the drum and croaker species.

Recorders won’t pick up sounds from nonsoniferous (silent) fish. Fish not heard but caught in the gillnets included alligator gar, spotted gar, menhaden, mullet, and Southern flounder. The vocalizations of some fish were heard but not caught in the gillnets, including the Gulf toadfish and silver perch.

PAM has several advantages over gillnetting: Fish are not hurt or killed, which sometimes occurs with gillnetting; the hydrophones can be left in the water, recording sounds for as long as their battery stays charged; and it is usually less expensive because it doesn’t take as much equipment, boat fuel, and manpower to implement.

The underwater recording units Souza used when working with TPWD cost about $3,500 apiece, can work for years, and require little maintenance, other than replacing the batteries every six to 12 weeks.

A noisy estuary is usually a good sign but a quiet estuary can be a sign of trouble.

After a big storm in the spring of 2021, the Mission River, which flows into Copano Bay (which is part of the Mission-Aransas Estuary) flooded and a deluge of freshwater entered the bay. The salinity of the water plummeted and saltwater fish, the bay’s usual inhabitants, fled toward the saltier water they require. Biological sounds in Copano Bay went silent; the only sounds Souza heard in the recordings were man-made—boat engines, lapping waves and the hum of airplanes flying overhead.

Souza has also learned that different fish make noise in different ways. Red and black drum, for example, have swim bladders that they fill and empty to go up and down in the water. The sounds they make literally resonate like drums.

“If it wants to sink lower, it’ll release some gas from that organ and it’ll start to drop a little bit lower into the water column,” Souza said. “And they have what’s called a sonic muscle sitting right against that swim bladder, and it’s almost like an elastic but when it vibrates it drums and produces that drumming sound.”

Sometimes Souza records black drums and other fish at a pier at the institute that protrudes into Aransas Pass, a busy ship channel leading from Port Aransas to the Gulf of Mexico.

On a moonlit October night, he carries his recording equipment with him to the end of the pier, uncoils the wire, drops the hydrophone into the water, closes his eyes and listens. The drums he was expecting to hear are silent but snapping shrimp are raging.

He passes over the headphones, which sizzle with the Snap! Crackle! Pop! sounds of old Rice Krispie cereal commercials. Souza’s smile lights up while sharing the shrimp’s chorus. “They have a big claw that they use but it’s not the claw that’s making the sound,” Souza said. “They close their claw so fast that it creates a bubble and when that bubble collapses and pops it makes that snapping sound.”

But it’s dark now and time to end this recording session. After a few minutes of listening to shrimp crackle and pop, he packs up his equipment and heads home.