From KERA News:

Federally qualified health centers, also known as community health centers, act as a safety net for uninsured and under-insured patients.

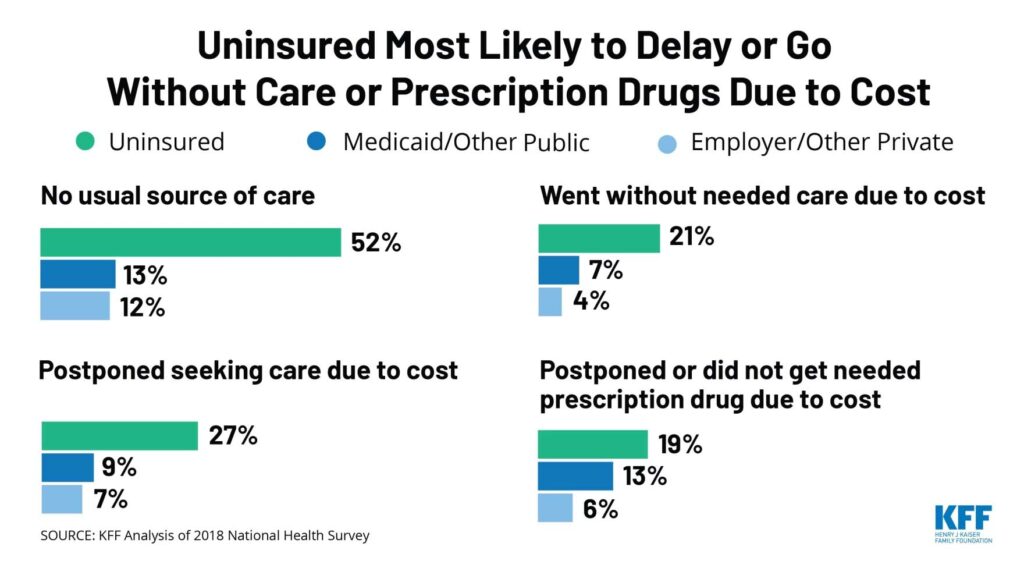

But in Texas, the clinics face more challenges because the state hasn’t expanded Medicaid. That leaves almost 800,000 people with limited options for health care, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation.

What would it mean for these clinics and the communities they support if Texas increased health care eligibility?