From KERA News:

More than one million Ukrainians have fled to Poland since Russia attacked their country almost two years ago, according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees.

While the numbers of Ukrainians finding refuge in Poland can be staggering, Barbara Muszynska says the humanitarian cost is something else again.

“You cannot imagine the chaos,” said the Polish education professor from the University of Lower Silesia, in Wroclaw, Poland. At the end of 2021 and into 2022, she spent five months in Denton at Texas Woman’s University, on a Fulbright Scholarship. She flew home a day before Russia invaded Ukraine.

“People with children, many mothers – because fathers were not allowed to leave the country – arrived to our country and waited for help,” Muszynska recalled.

Thanks to research she and TWU colleagues developed, they were able to help.

“We reached TWU because we needed new methods for teaching refugee students that would help them find the sense of belonging,” Muszynska said.

She brought back with her some innovative methods of teaching that TWU language professor Mandy Stewart said are inspiring incoming Ukrainian children to learn Polish faster than expected.

Techniques were initially tested in a few classes in Poland of about 50 elementary students – some Polish, some Ukrainians.

“They were using Polish more because they were engaged in classroom learning,” Stewart said. “So instead of just sitting there while the teacher was going through, you know, maybe rote memorization or nothing that connected with them, they were engaged in what they’re learning.”

What helped engage them?

Instead of giving up their own language – Ukrainian or Russian – they’re using it to learn Polish – by telling personal, often emotional stories. That’s not been done before in Poland, said Stewart.

It’s also a different way of learning than TWU graduate student Maria Torres remembers. She’s a bilingual teacher in the Denton Independent School District.

“I grew up speaking Spanish and English at school and at home,” Torres said. “The sink or swim (method)? That’s how I grew up.” That’s because English and Spanish were intermingled up until third grade. But after that, only English was used, and in every subject.

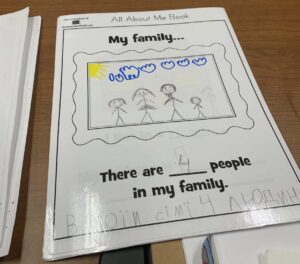

Torres didn’t want that for her 1st grade English language learners. So she helped them create what she calls a bilingual book. Students fill them with pictures of themselves & their family members, what they like to do or places they like to visit.

They write captions in their native language as well as the one they’re learning. Torressaid it makes them want to tell their own stories to classmates – using their new language.

Torres typically teaches English to Spanish speakers in Denton ISD, but she recently had Ukrainians in her class, here because of the war. She remembers how one boy, Illia, began to open up.

“I asked if they could have any superpower, what would they have? And Illya said he would want to have– you know, Dr. Strange could open portals – to open one to Ukraine so he could bring his family,” Torres said, choking up.”

“And when he said that, I was like, oh my gosh, just, I felt like it was just one of those things that, ‘you know, we’re just going to help these children and learn a little bit about them,’ but it just became bigger than that.”

Bigger because of the intense emotions swirling around separated families, especially those distanced because of war. It’s what teachers in Poland have faced now for nearly 2 years.

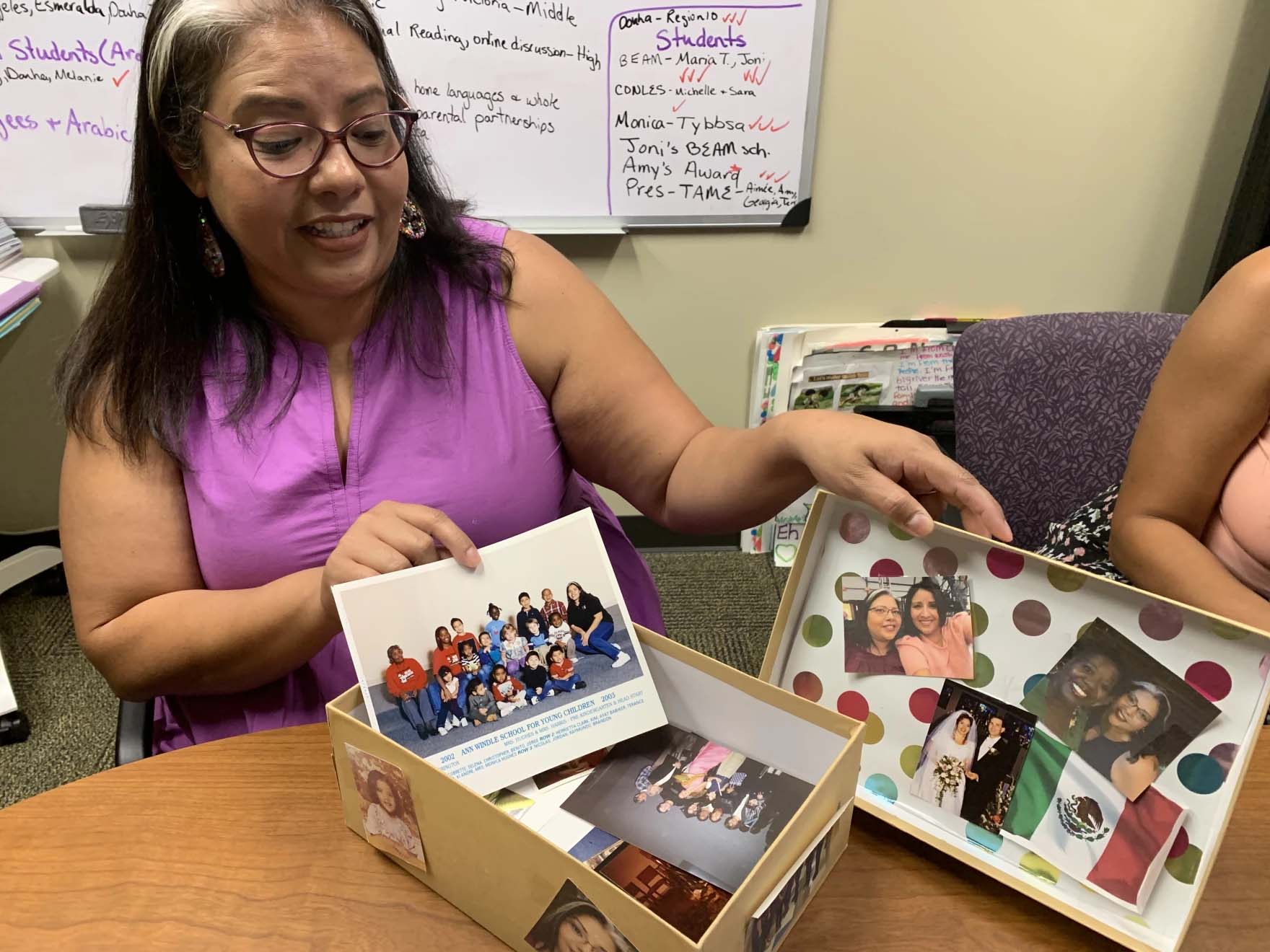

The bilingual book helped, as did another tool used by a different TWU student who’s also a bilingual teacher. Monica Hughes created what’s called an “identity box.”

Students put small and meaningful objects about their lives in a display box.

“Pictures, things that represent their religion, just different things that were also their favorites, like food that they ate at home,” Huges said. “We’ve had several kids, too, that identified with that, like, oh, you eat this at home? I eat that at home!”

In Poland, Professor Barbara Muszynska said using personal connections to free up emotions unlocks the students’ desire to share their stories through their own language and the one they’re learning.

“By inviting students’ languages into the classroom, student engagement became higher,” she said. “They were more excited about telling their stories and they were more excited to read in one or two languages at home.”

“That kind of a big impact we did not even anticipate when we started.”

That big impact led to a prize – the European Language Label – awarded to the program in November. Maybe bigger than a prize, the program is helping young Ukrainians more readily adapt to a new country without losing a tie to the home that had to leave.