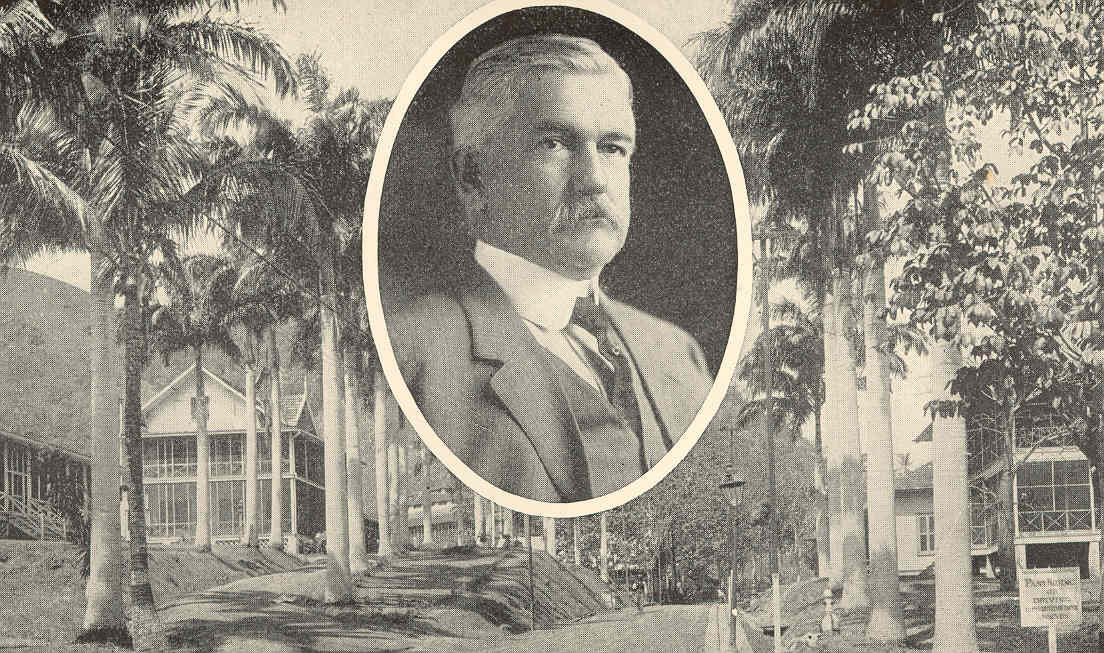

I’m walking on the veranda of the Gorgas Building at Texas Southmost College in Brownsville. It’s named for the famous Army physician, William Gorgas, who was sent here to Fort Brown in 1882. This building was already here when he was. It was the hospital he ran. What he would learn here, and what would happen to him, would change the world.

Gorgas was just 27 years old when arrived at Fort Brown. There was a full-blown yellow fever epidemic raging at the time. It was so named because it turned eyes and skin yellow. About half the people who came down with it, died. Yellow fever was not only deadly, it was quick. You could feel fine on Wednesday morning, have symptoms kick in that afternoon, and be dead by Saturday.

Gorgas fought yellow fever head on. He didn’t yet know that mosquitoes spread it, but he did know that good sanitation and quarantining patients was useful. He launched public health measures that helped cut short the epidemic. Perhaps the best thing that happened to him during this time, and it will seem a strange thing to say, is that he came down with yellow fever himself, but it gave him lifelong immunity. He vowed to make fighting the disease his life’s work.

His next significant posting in his war on yellow fever was to Cuba. It was there that the research of the Cuban doctor, Carlos Finlay, had laid out a convincing case for mosquitoes being responsible for transmitting the illness. Walter Reed, a name you likely recognize, tested Finlay’s theories and proved without a doubt that mosquitoes were responsible. Then Gorgas put the knowledge to practical use with fumigation, screening and outlawing open cisterns and standing water. Astoundingly, those efforts virtually wiped out yellow fever in Havana in a couple of years, reducing cases from thousands a year to fewer than 20.

Then Dr. Gorgas made his big leap onto the world stage. You will remember the French had tried to dig the Panama Canal but failed miserably because they lost thousands of workers to yellow fever. Disease drove them out and silenced the steam shovels. The Americans, in a cannot-fail bid to do what the French couldn’t, resumed the dig. But in the first years, yellow fever and malaria threatened to drive the Americans out, too. Some said it would have taken 50 years and 80,000 lives to finish the canal under those conditions.

Gorgas was brought in to solve the problem. But the political leaders in charge didn’t want to hear anything about his mosquito theory. They told him to keep that crazy theory to himself because “everyone knew that those tropical illnesses came from miasma – bad air.” Hell, the word “malaria” itself came from Italian, translating, verbatim, “mal” and “aria” – translation: bad air.

Gorgas learned as Galileo did that getting the world, even scientists, to ditch a centuries old belief system in favor of a new one, has always been unfathomably difficult.

Gorgas wanted to take what he had learned in Brownsville and Cuba and put it to work on a grand scale in Panama. He applied for a million dollars to protect Panama. The U.S. gave him $50,000. But with such poor funding, hundreds of workers were dying each month and the Americans risked being embarrassed by failure, just like the French. Teddy Roosevelt himself intervened and more or less said, “Give Gorgas what he wants.”

So it was then that Gorgas screened all the houses, buildings and particularly the hospitals in the Canal Zone. This was essential because a patient could only get yellow fever from a mosquito that had bitten someone with yellow fever. Gorgas also had an army of fumigators at work across the isthmus every day.

As he had in Cuba, Gorgas got rid of standing water and required covers on cisterns. He also drained swamps and treated undrainable waters with oil to keep larvae from forming. Within two years yellow fever had been completely eradicated from Panama.

Gorgas was considered the medical hero of the canal because, without his work, the engineers and diggers and construction workers could never have done their work. Gorgas, without question, made the canal a reality.

After Panama, Gorgas eventually became Surgeon General of the U.S. Army and was knighted by the King of England for his work in tropical diseases, from which the British greatly benefitted.

So here I sit on the veranda of his old hospital at Fort Brown in Texas. The building still bears Gorgas’ name. I also admire the fact that his name has a place of honor 8,000 miles away on the side of the London School for Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

Here at Texas Southmost College, funded from this very building, are many fine programs in nursing and health professions active today. I think Gorgas would be pleased.