Fifty years ago today, on April 4, 1968, Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated on a hotel balcony in Memphis. King was the preeminent leader of the American civil rights movement, and advocated nonviolent resistance to discrimination against black Americans. King had gone to Memphis to support sanitation workers who were in a labor dispute with the city.

His murder shocked and saddened the nation, making a particular impact on African-Americans, for whom King was a hero and acted as the conscience of the movement for change.

Bob Duckens was president of the Prairie View A&M choir in 1968. The choir was staying at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis when King was there. They were passing through on a tour. The Prairie View choir performed for King two weeks before the civil rights leader’s death.

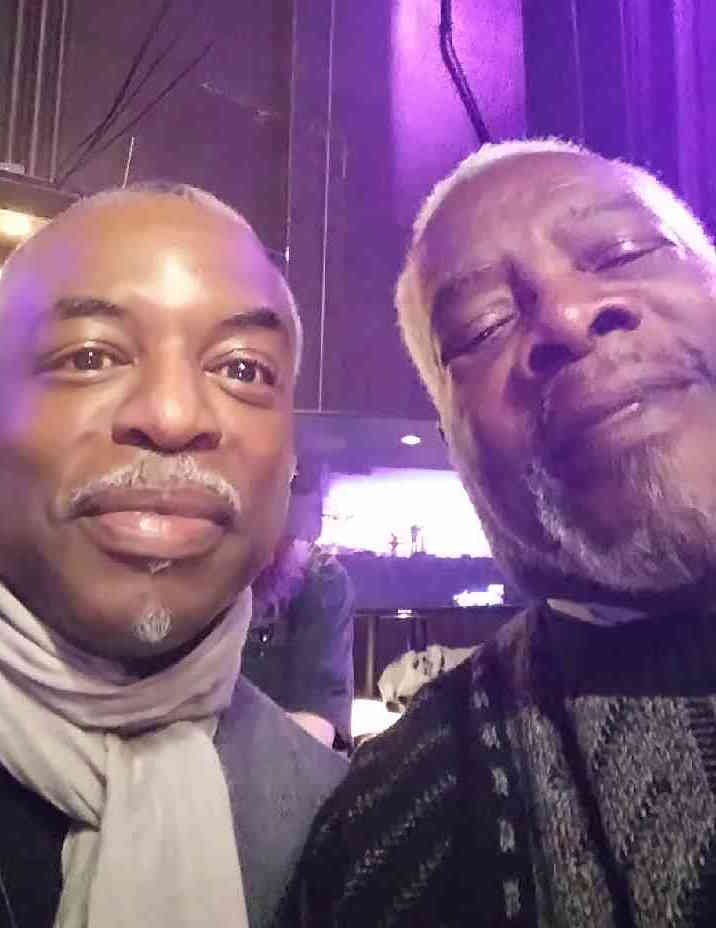

On Monday night, Duckens’ brother, Dorceal Duckens, conducted a choir in Memphis that reenacted that 1968 performance.

Bob Duckens says the Prairie View A&M choir waited to perform for King until after midnight because King had been tied up with meetings until then.

“He was so gracious and so kind. And I will never forget the look on his face, even 50 years later,” Bob Duckens says. “It’s just unbelievable the glory that was on the man.”

Duckens points out that the civil rights movement led by King, a minister, began in black churches.

“This was a spiritual movement that started in the church,” Duckens says. “This wasn’t just a movement. It was more than that.”

Dorceal Duckens says the choir that gathered this week sang the same piece, “Alleluia,” by Randall Thompson. Duckens was able to bring six of those who sang for King in 1968 to the reenactment.

“Man, what a fabulous opportunity,” he says. “The audience just went crazy. There were people crying in the audience when we sang Monday night. It was just awesome.”

Remembering how he felt when he heard the news of King’s murder, Bob Duckens says he was angry.

“They had just killed my hero,” he says. “This was a man who was willing to give his life for humanity and for people who didn’t have a voice.”

Dorceal Duckens agrees. Today, as he hears a recording of CBS Evening News Anchor Walter Cronkite’s reporting of King’s death, he remembers where he was when the news broke.

“I was at Prairie View when we got the news, and the campus just went into an uproar,” Duckens says. “It was just horrible. But everybody was angry, hurt, sad. So it created a lot of feelings that you’ve tried to hold back, or that you’ve tried to get rid of over the years, because of the treatment. Being a black man in America has not always been the best thing. But thanks be to God, we’ve survived. We’ve made it.”

In 1968 some white Americans’ first reaction to news of King’s murder was fear that African-Americans would respond with violence. The Duckens brothers say that they and others who admired and followed King continued to honor him by responding to his credo of nonviolence.

“We remembered Dr. King – because he was extremely strong on never having violence or evil,” Bob Duckens says. “You treat evil with nonviolence. And that’s what kept this nation together.”

“Only love can destroy hatred,” Dorceal Duckens says.

The Duckens brothers emphasize that along with preaching a nonviolent response to hatred, King went to Memphis to advocate for economic equity.

“Every time in this country we start thinking and talking about economic equality, then we bring up other social issues to drown that out,” Bob Duckens says. “If we had economic equality, it would take care of a lot of social issues that we have today. And the man gave his life for that.”

Written by Shelly Brisbin.