From the American Homefront Project:

Navy Petty Officer 3rd Class Devon Rideout returned to her apartment in suburban Oceanside, California after her shift at Naval Hospital Camp Pendleton. It was a summer Friday afternoon in 2018, and the 24-year-old Navy corpsman took her new puppy, Chip, for a walk.

When she returned, her upstairs neighbor — a man she did not know — was waiting outside her door. He was holding a revolver.

Rideout died just steps from her home in a quiet apartment complex that was popular with many service members working at nearby Camp Pendleton. Her killer, Eduardo Arriola, was a former Marine who had been kicked out of the service two years before.

According to court records, Arriola deserted from the Marine Corps in 2014. When he was caught in 2016, the Marines charged him with desertion. However, military psychiatrists found Arriola was delusional and having hallucinations. They diagnosed him with schizophrenia.

The Marines found him not mentally competent to stand trial at a court-martial proceeding and separated him from the service.

The medical diagnosis should have landed Arriola in the National Instant Criminal Background Check System — NICS. That would have kept him from buying a gun.

However, according to a pair of lawsuits brought by Rideout’s mother, Arriola’s name was never added to the system.

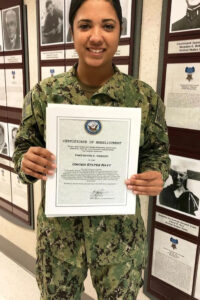

Devon Rideout holds her Navy reenlistment certificate in 2017. Her mother says Devon planned to earn a degree in occupational therapy and wanted to work with veterans. Courtesy Leslie Woods

“I can’t even tell you the rage … inside of me,” said Leslie Woods, Rideout’s mother. “It was all premeditated. He should not have had that gun. He should have never had a gun legally.”

Evidence in Arriola’s criminal trial revealed he purchased a 5-shot revolver at an Oceanside, California gun shop just weeks before killing Rideout. According to court documents, a list of names was found in Arriola’s car, including Rideout’s.

After shooting Rideout five times, Arriola stayed at the scene and wouldn’t let neighbors render aid. When police arrived, he told them she had been “trespassing.”

Arriola was sentenced to life in prison last year.

Woods is suing the federal government and the state of California for negligence and wrongful death. Eugene Iredale, Woods’ lawyer, said the law is clear — Arriola should not have been allowed to buy a gun.

“In this case, all you needed was compliance with the law that has been in effect for over 30 years – the Brady Act,” Iredale said. “That’s why we have such a powerful case.”

According to the suits, even though the military failed to report Arriola to the FBI, his name was flagged by the California Department of Justice when the gun dealer submitted his background check because of his 2016 arrest and desertion charge. The state then asked the Marines what the outcome of Arriola’s court-martial was.

The Marines told the state Arriola had been found incompetent to stand trial, according to an email exchange cited in the suit. But that was the end of the inquiry into Arriola, the suit says, and he was allowed to buy the gun anyway.

“The military has a long track record of not reporting this information when it should,” said Lindsay Nichols, the policy director of the Giffords Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence. “Going back to the 1990s when the background check system was first established.”

The Pentagon’s internal watchdog, the Inspector General, backs Nichols’ claim. Reports from the 1990s to 2017 found the Pentagon repeatedly failed to report service members to the FBI in accordance with the Brady Law.

The best-known case is Devin Kelly, an Air Force airman whose 2012 domestic assault conviction should have landed him in the FBI’s system.

The Air Force failed to report him, and in 2017 Kelley killed 26 people in the First Baptist Church of Sutherland Springs, Texas.

In 2022, a federal judge ordered the Air Force to pay more than $230 million to Sutherland Springs survivors and families. In April, the case was settled for $144 million.

The Texas shooting led to reforms at the Department of Defense.

A 2020 Inspector General report found that prior to the Texas mass shooting, the service branches reported disqualifying criminal information to an internal Pentagon manpower component, but the information didn’t always get to the FBI. Now, service branches submit it to the FBI directly, the Inspector General found.

Rideout’s killer was separated from the Marine Corps in 2016, so it’s unclear whether this change would have affected his case.

However, the 2020 Inspector General’s report looked only at whether the services reported people who had been convicted of crimes. Rideout’s killer wasn’t court-martialed and therefore never convicted.

The Inspector General hasn’t reviewed whether mental health adjudications are being reported, but a spokesperson said that would fall under the military’s legal offices rather than its law enforcement components.

For Woods, the loss of her only child has left her with little family. She moved from Northern California to Vista — Oceanside’s neighboring city — after her daughter was killed. She wanted to be in the area she said Devon loved so much.

“I just live in my memories of her,” Woods said. “It’s hard for me to get out of myself — to focus on things. She never leaves my mind. Absolutely never.”

Woods said she hopes the courts force the state and military to change their processes so no one else slips through the cracks.

“They need to take the law seriously.” Woods said. “(They’re) too big and powerful an entity — the military, the DOD, the government and all that — to even let this stuff happen.”

This story was produced by the American Homefront Project, a public media collaboration that reports on American military life and veterans.