As cars buzzed past on a nearby road and an aircraft hummed overhead, crowds of children gathered in a field on the George Ranch in Richmond, which is located about 30 miles southwest of downtown Houston.

They were there on a field trip for the ranch’s Black Cowboy Student Day in February.

From behind a fence, a throng of cattle hands raced past on their horses, herding steers into a barn.

“Hey-yup! Hey-yup!” one of the cowboys shouted, urging on his horse.

As the Houston Livestock Show and Rodeo continues, many residents are turning their focus to the area’s cowboy culture.

But just outside the city, some are working to preserve a key piece of that heritage: the history of the region’s Black cowboys.

The George Ranch first started as a plantation that relied on the labor of enslaved African Americans.

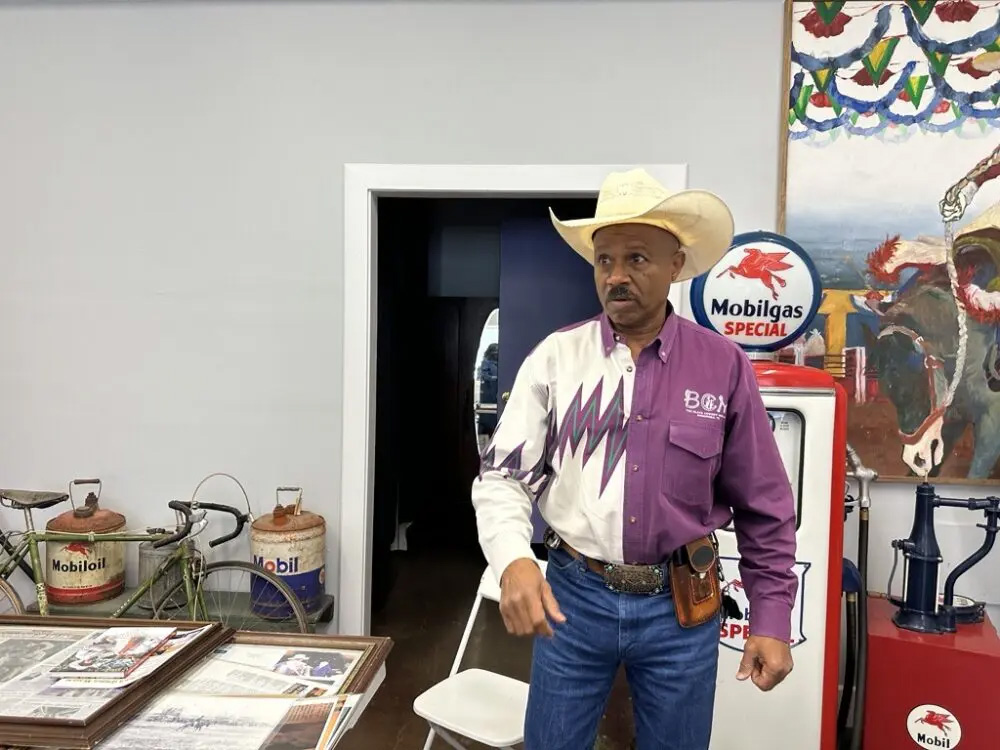

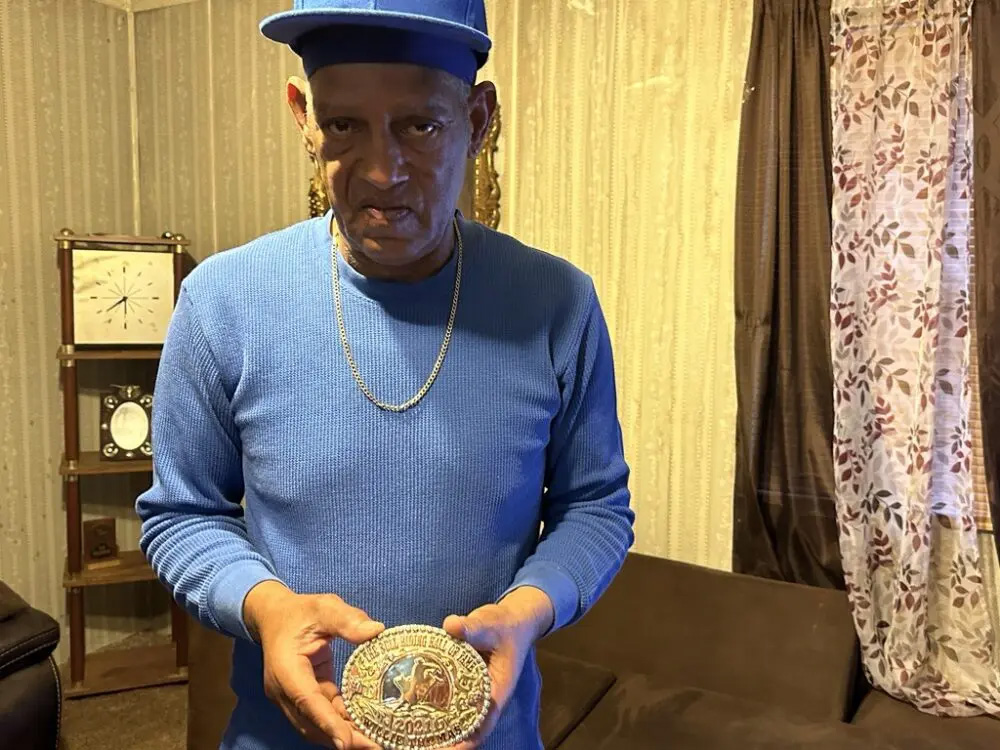

“He had a house boy, a yard boy and a boy that worked the cows,” Larry Callies explained from his museum in Rosenberg. “He was called a cow boy.”

Callies, who runs the Black Cowboy Museum, says the first cowboys were enslaved African Americans. White men were known as cow hands.

That is until Hollywood learned of the term.

“They didn’t know where the cowboy came from,” Callies said. “And they white-washed it.”