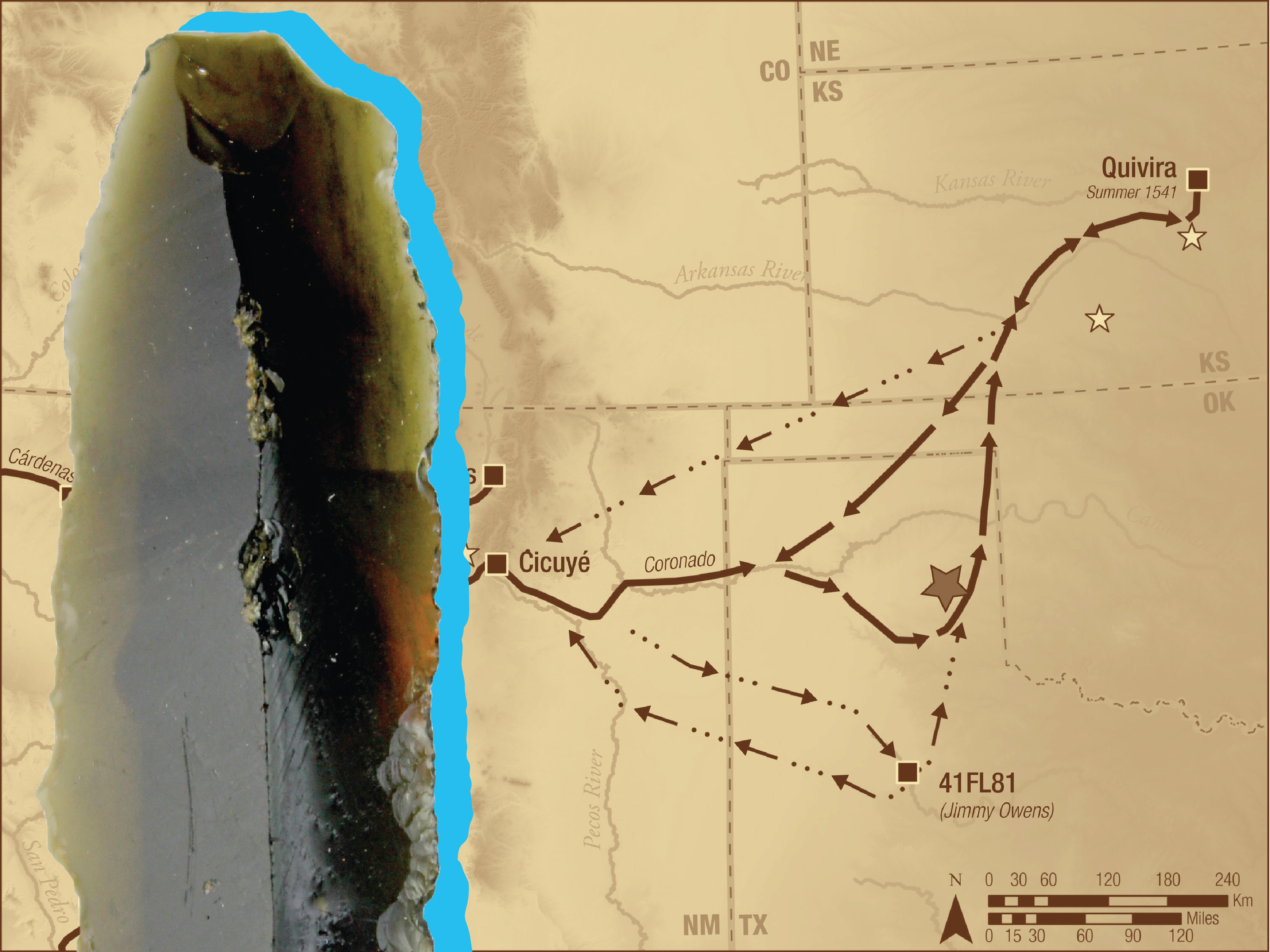

Almost 500 years ago, a caravan of roughly 2,000 people crossed the Texas Panhandle in their search for a city of gold. They were led by Francisco Vázquez de Coronado, a Spanish conquistador whose journey in North America stretched from central Mexico to modern-day Kansas.

Coronado never found that fabled gold. But the Spanish explorer and his fellow travelers left behind plenty of small treasures for us to find. One of them may have been recently described by anthropologist Matthew Boulanger, director of the Archeology Research Collections at Southern Methodist University.

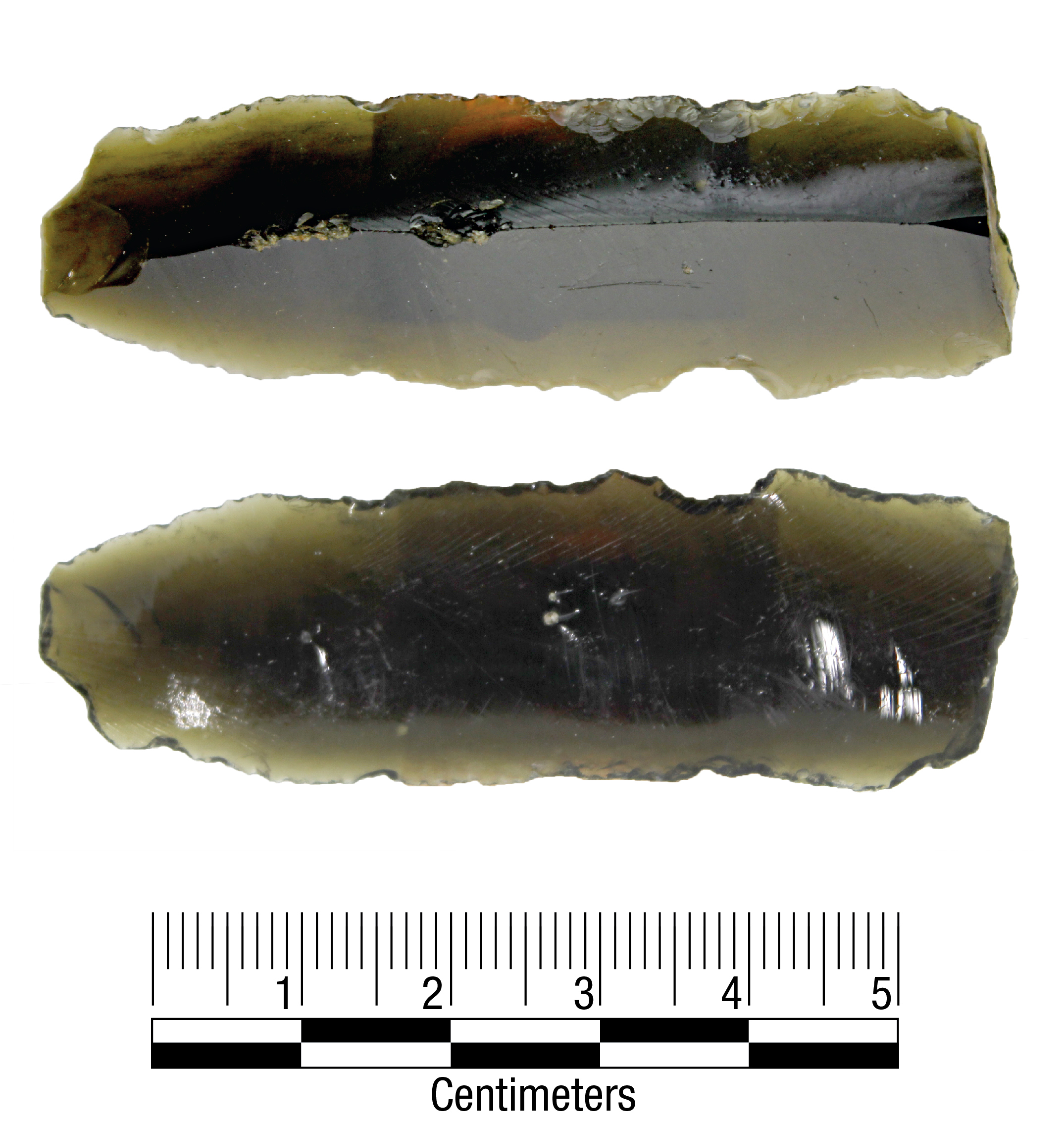

Boulanger spoke to the Standard about a piece of obsidian that may have been dropped by someone with Coronado. Listen to the interview above or read the transcript below.

This transcript has been edited lightly for clarity:

Texas Standard: Tell me a little bit about the fact that you recently got a chance to take a very close look at a piece of obsidian found in the Panhandle. Why is that so significant?

Matthew Boulanger: Well, it’s significant because apart from this latest find, we only know of one other site in the entirety of Texas that seems to have been visited by Coronado. And this would be the second such site that we’ve found.

It places it right along the pathway of his journey that has been reconstructed from his journals and other things. But this would be the first physical evidence of it, particularly up in the Panhandle.