This is not a ghost story. But it’s a story about the ghost of a dream – a French dream – to build a colony for Frenchman fleeing political and economic upheaval that began in Paris and swept across Europe in the late 1840s.

“And this was also around the same time as the French philosophers who were espousing a kind of Democratic Socialism, wherein they could establish colonies somewhere else and have their own community where they could be self-sufficient,” says Paula Bosse, who writes for the Dallas history blog Flashback Dallas. “And a lot of these people went to the United States.”

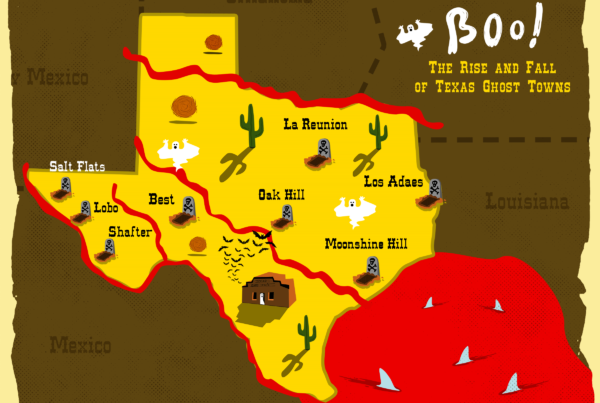

Several hundred landed across the Trinity River from Dallas. Back then, the Big D was just a scruffy little frontier town. The new settlers named their 2,000-acre colony La Réunion, and they shared a singular ambition: a society where everyone worked together and everyone shared. All for one and one for all.

“There were no burdens placed on them by the ruling party,” Bosse says. “Basically, they were in charge of their own lives. The United States in the 1850s was pretty wide open, especially in Texas.”

It was the wild West – and that’s exactly what La Réunion founder Victor Considérant wanted. He was a prominent Democratic Socialist, who fled France in 1852 in search of a new life for himself: ardent critics of capitalism, proponents of direct democracy and despondent political émigrés.

He fell in love with north Texas and returned to Europe with a blissful account of beautiful cliff sides, vast plains and a landscape comparable to the French wine country. He included all of those riveting details in a publication called “Au Texas,” what Bosse considers the ultimate sales pitch.

“I think a lot of what he was saying was exaggerated to get people to join a cause, come with him and invest in his company,” Bosse says. “They would come in dribs and drabs. A lot of times people would arrive, they’d look at the place and say ‘nah,’ and leave.”

And that’s why La Réunion only lasted three years – and all that physically remains is a fenced-in cemetery in West Dallas with a few dozen weathered tombstones: the La Réunion Cemetery, also known as the Fish Trap Cemetery.

This is where 85-year-old Rose-Mary Rumbley often gives history tours. She points through the chain-link fence to a tall white headstone she says belongs to a Monsieur Reverchon. She then looks down at pile of rubble.

“But you can see this one right here. This is broken down, and they’ve just stacked it up,” Rumbley says. “It’s sad, whoever that is. The lawnmower must have hit it or something, but these are all Frenchmen.”

Rumbley says her mother really piqued her interest with the tales she used to tell about the men and women she knew from La Réunion. The colony was technically before her mother’s time. She was born in 1894. But her family had a bakery, where former settlers and then their children would buy bread.

“I questioned that. I said I thought they were all together, one for all and all for one, and baked their own bread. And mother said, ‘no, they were very artistic people and they preferred to buy their bread.’”

They were artisans, store clerks and academics – not the kind of people to make a go-of-it at self-sufficiency. History writer Paula Bosse said that wasn’t the only problem:

“The land that Victor Considérant purchased was not meant to be farmed on. It was limestone,” Bosse says. “But add to that the drought, the bad weather, the grasshoppers and the fact that there were no farmers.”

America wasn’t the dream they had hoped for either. They opposed slavery, which had become a violent state of affairs in Texas – and the locals weren’t particularly fond of such “free-thinking” Europeans. They had instead stumbled into a geographic, economic and political nightmare.

By most accounts, La Réunion was a failed socialist experiment. But Rose Mary Rumbley has a different theory.

“I always said it was the heat. I think they could’ve made it if it hadn’t had been so hot,” she says.

Fast forward more than a century – and it seemed this bit of Dallas history was totally forgotten. Then in 1972, came John Scovell. He was a young accountant at the time, hired by Ray Hunt (of Hunt Oil Co.) to spearhead a new project in downtown Dallas: what you now know today as Reunion Tower – that glittering orb in Dallas’ night sky

“I’d like to tell you that we were geniuses and we understood the future and we had this great plan for a tower and we were going to change the skyline of Dallas. Well, no,” Scovell chuckles.

Scovell is now the Chairman of the Board for Woodbine Development Corporation, the firm that built the Reunion District and its iconic tower. A marketing firm had originally pitched naming the area “Esplanade,” but Scovell found it lackluster. Everything was named “Esplanade” in the 70s, he said.

So he did a little digging of his own into Dallas’ history and was ultimately charmed by the little town that never was, just about four miles east across the river. He tied La Réunion back to the concept of reunions – for friends and family – and the name stuck. Even though the story didn’t.

“I think Dallasites, in particular, Texans, we’re not big veterans on history,” Scovell says. “But it was amazing. The La Réunion colony did have an impact on this community. The cultural side of Dallas, Texas, can trace a lot of that back to those settlers, so we take great pride in [that].”

From the top of the Reunion Tower, everything is shiny and new, and history is easy to forget. But never forget, this great American city was born from a French failure. La Réunion may have collapsed more than 100 years ago, but its residents – with their skills, their worldly perspectives and their wine – made Dallas what it is today.