From El Paso Matters:

Haz clic aquí para leer este reportaje en español.

Cristhian was all but dead at 23, intubated and under an induced coma. As he lay on a hospital bed struggling to survive, his family had begun to mourn him from more than 2,200 miles away.

They thought he was dead.

His parents, Samuel and Serafina, believed they had lost the youngest of their seven children. His pregnant wife, Mayra, fell to her knees in agony, thinking her unborn son would never know his father.

Social media and early news reports told them that Cristhian’s journey from Honduras to the United States in search of the American Dream ended in a nightmare: A devastating fire in a provisional migrant detention center in Ciudad Juárez across the border from El Paso killed 40 people and injured 27 more.

That was Monday, March 27, 2023, a day that marked one of the deadliest tragedies in a migrant center in Mexico.

Cristhian survived – but not unscathed. He spent more than a month in Juárez and El Paso hospitals, eventually discharged with an array of lingering health issues – and emotional scars he doesn’t like to talk about.

“Why not me?” Cristhian, who asked to be identified only by his first name, asks himself about why he wasn’t among those who died. Maybe it was just God’s will that he live, he said. He sits in a North Texas suburb home where he’s staying with family while in the U.S. under temporary humanitarian parole. “Why was I saved?”

A year later, many questions about the fire remain unanswered. The incident is still under investigation and 9 of 11 people charged in the case remain behind bars in state prisons in Juárez awaiting their trials.

A months-long investigation by El Paso Matters, La Verdad and Lighthouse Reports details the chaos of that night, showing a number of lapses in safety protocols beyond the cell door key authorities allege could not be found. The news organizations obtained 16 hours of security camera footage outside and inside the center and thousands of pages of documents, including court affidavits and other records. They reviewed the security camera footage frame by frame, recreating the incident using 3D modeling.

Several survivors interviewed for this investigation confirmed previous reports that detained migrants lacked food and water after being rounded up off the streets and put into the overcrowded holding cell at the city’s National Migration Institute – Mexico’s immigration agency known as INM. They said they were verbally mistreated and confronted with threats of deportation.

The news outlets are only identifying survivors as each requested because some fear for their safety and persecution.Previously leaked video snippets from facility security cameras have shown vinyl sleeping mats in the men’s holding cell on fire – and smoke quickly overtaking the area as uniformed officials walked around the facility without opening the cell.

‘We’re not going to open it for them’

But previously undisclosed security camera footage and court documents obtained by the news organizations show a number of safety failures that night: Uniformed authorities looked for fire extinguishers that were missing or not working properly, and considered using water hoses to put out the fire. None of the seven smoke detectors in the facility functioned, and there was no sprinkler system. Two other access points to the cell had previously been sealed off, one walled off completely.

There was an unhurried attempt to locate the keys to a side door that would have helped dissipate the smoke – with various uniformed people asking each other who last had the keys. Various officials throughout the day had opened and closed the cell as well as the side door with two different sets of keys.

And while the majority of the video has no sound, the news organizations discovered two cameras near the main entrance with muddy audio.

“Ay un desmadre!” one private security guard can be heard saying. “It’s a disaster!”

One voice comes across a little more clearly.

“A ellos no les vamos abrir, ya les dije a los güeyes,” a woman in a migration institute uniform says in Spanish as she talks and texts on her cell phone.

“We are not going to open (the cell) for them, I already told those guys.”

It’s unclear with whom she was talking on the phone.

The woman was one of two INM agents in charge during the night shift that day, documents reviewed by the news organizations show.

The INM official is one of the 11 people charged in the incident and remains jailed. The news organizations attempted to contact the woman for comment through her attorney, but did not receive a response.

Eight other INM authorities and private security guards are charged in the case as prosecutors have stated that the incident showed a “pattern of irresponsibility.”

The head of the National Migration Institute, Francisco Garduño Yáñez, has been charged with criminal conduct for failure to perform his duties, though a year later he remains free – and on the job.

The two Venezuelan migrants accused of setting the fire are behind bars.

The news organizations attempted to reach them and others charged in the case through their attorneys or families and either received no response or their representatives couldn’t be found.

Officials at INM refused to comment on this investigation, though they have repeatedly pointed to the “missing” keys as the reason nobody opened the men’s cell. The videos show that the keys were at the facility as 67 people trapped inside the men’s cell suffocated from the toxic smoke.

Additionally, court affidavits show that an unidentified guard handed firefighters on the scene a key to the exterior door – minutes after they had sledgehammered a hole through the wall to let out the smoke.

Fifteen women detained in a nearby cell were released by a private security guard when smoke started seeping into their dormitory. “Oh my God! Oh my God!” the women cried as they hurriedly exited the building. The women didn’t receive any medical treatment on the scene.

‘We are going to die!’

Cristhian, who has a shy and quiet demeanor, won’t talk much about the details of that night or who might be at fault. He hopes justice is served, he said, but is now focused on moving forward.

None of that, however, sits well with Estuardo, a 25-year-old former security guard from Guatemala who survived the fire. He said the deaths could have been prevented.

“They could have totally opened the door, but they didn’t want to open the door,” he said in Spanish during an October interview in an El Paso migrant shelter where he was staying temporarily under humanitarian parole. “They just argued that the key wasn’t around. How could the key be missing? Moments before, they had unlocked the cell door.”

Authorities in charge of the detention center knew of the threat of the fire, Estuardo said. But the threats – and later their cries for help – fell on deaf ears.

“Nos vamos a quemar! Nos vamos a morir! Tenemos hijos!” Estuardo recalled he and other detainees shouting. “We are going to burn! We are going to die! We have children!”

The detention facility closed down after the fire. Garduño in May announced it would be replaced with a new building near the Ysleta-Zaragoza international bridge some 15 miles east and would be supervised by Mexico’s National Commission on Human Rights. He didn’t provide a timeline for the new facility, which has yet to open.

The fire led the human rights commission to investigate the incident and visit immigration stations across the country, stating that the “regrettable events” in Juárez were the “irreversible result of a dysfunctional immigration policy.” The commission released its “Special Report on the Conditions of Immigration Stays and Stations” on Feb. 9.

The report confirms that the INM Juárez facility had a shortage of food, toilet paper and drinking water for the detainees, citing that some migrants had not had a drink of water for more than 12 hours. The poor conditions led migrants to protest by burning the mats – a common practice in other migratory stations that the commission report states the INM did not address to prevent from happening again.

The commission also states it had monitored six immigration stations between Jan. 30 and Feb. 3, 2023 – including the one in Juárez – as part of its regular checks. However, commission personnel who visited the provisional facility faced “obstructive behavior” because they were initially denied access and were not allowed to take cameras inside once they were granted entrance, the report states.

Friends on a journey

“Con lo que me pasó, no me arriesgaría,” said Cristhian, the migrant from Honduras. “With what happened to me, I wouldn’t take the risk again.”

He described his desire to migrate as personal. It was about family: “When I left home, I committed that God’s will be done and that if He allowed me to come here, that it would be to help my family.”

Cristhian worked on his parents’ small campo in Naranjito, a town of about 13,000 people in the western edge of Honduras about 25 miles from Guatemala.

The family farmed coffee beans and simple grains. He was married, and his wife was expecting their first child together. He had started to build a home for his budding family, but the campo was barely making enough for the family to eat, he said.

“Me arriesgo?” Cristhian asked himself. “Should I take the risk?”

He and a group of childhood friends from the nearby village of Nuevo Porvenir in the town of Protección, Santa Barbara, made the journey together.

The friends were from among the 55 families who had been displaced by Hurricane Mitch in 1998 when the village was called simply “Porvenir,” according to the Honduran online media outlet Contra Corriente.

The hurricane destroyed farms and crops there, and families rebuilt their homes out of plastic and wood just a few kilometers away, the outlet reported. About 375 people now live in the Nuevo Porvenir village, the latest Honduran census estimates show.

Looking for opportunities not found in their villages, the men headed north to Mexico and then traveled via charter bus to Juárez.

They were swept up by immigration officials, city police and Mexican National Guard members, and were detained in the same center at the foot of the international bridge connecting the U.S. and Mexico.

At about 9:30 p.m., the detention center fire started. Fire trucks and ambulances arrived 13 minutes later. The first person was brought out nine minutes after that.

Not everyone made it out alive.

‘It was like a movie that would not end’

A paramedic from the Red Cross in Juárez describes the scene as “disturbing.”

“The most impactful thing is that you saw them take out one person, and another, and another,” Adrián Fernando Meléndez de la Torre, a Red Cross coordinador who responded to the scene, said in Spanish. “Parecía película, que no podía terminar.”

It was like a movie that would not end, he said, describing several runs he made taking severely burned patients between triage areas and hospitals. Most of the men were unconscious, he said, while a few were conscious but unable to speak.

De la Torre said the scene was cleared of victims seven hours later.

Cristhian, for his part, said he has no memory of the scene described by de la Torre.

He didn’t see how the fire started, and only recalls hearing some commotion among the detainees before being overwhelmed by the smoke. He didn’t have time to think, to react, to drop to the floor or to put his shirt over his mouth.

He fell and lost consciousness.

When he woke up, he was at University Medical Center of El Paso, where he had spent 15 days. He had spent 29 days at the General Hospital in Juárez before that. He suffered internal burns and pneumonia. He lost 20 pounds. He still has trouble breathing “normally” and has “very frequent” headaches, he said.

The first person he saw when he opened his eyes was his pregnant wife. His brother, Exequiel, was also there.

“I cried with joy when I saw (my wife),” Cristhian recalled. “She put my hand on her pregnant belly and told me, ‘Our son is in here. Spirits up. Be strong because I need you.’”

His three friends didn’t have the same fate. They died of asphyxia from smoke inhalation.The bodies of Edin Josué Umaña Madrid, 26; Jesús Adony Alvarado Madrid, 32; and Dikson Aron Córdoba Perdomo, 30, were flown back to Honduras more than two weeks after the fire. The three friends had joint funerals and were buried near each other in their village of Nuevo Porvenir, La Prensa of Honduras reported.

They were three of six Hondurans who died in the fire. The three others were José Ángel Ceballos Molina, 21; Óscar Danilo Serrano Ramírez, 37; and Alis Dagoberto Santos López, 42. They had separate funerals in their respective hometowns.

Cristhian was among six survivors from Honduras.

“I’m grateful to God for that opportunity to see my son born and to be with my wife. So many others who died cannot do so,” he said.

After receiving parole, he traveled to Arkansas to see one of his brothers, who had migrated to the U.S. years earlier. His son, Jahaziel, was born there. Cristhian, his wife and baby moved to Texas, where they live with Exequiel and a brother-in-law.

Exequiel says Cristhian shows signs of PTSD, anxiety and depression when he suddenly goes quiet and stares into nowhere, his eyes tearing up and having to snap back into today.

“He appears to be OK, but he’s not the same as before,” said Exequiel, who was granted humanitarian parole to join Cristhian in the U.S. “He doesn’t want to talk about the incident but we know it haunts him everyday.”

The family is considering applying for asylum, though Exequiel is not sure what that will mean for the wife and 2-year-old daughter he left behind.

Their immigration hearings are set for late 2025.

Three national days of mourning

Cristhian’s story resonates with other survivors.

Estuardo, the security guard from Guatemala, was flown to the national burn center in Mexico City for treatment in critical condition, spending more than 40 days there before being released. He suffered burns to about 25% of his body, including his head and ears, which he tries to hide under a baseball cap, as well as burns in his airway, kidney injuries and digestive tract bleeding.

His right hand was amputated.

Standing about 5-foot-6 with a stocky build, Estuardo said losing his hand was especially emotional because he was counting on his youth, strength and “working hands” to land work in the United States. Any kind of work would do, he said.

He hoped to be able to quickly start sending money back home to his parents, who live in a small agricultural town of under 50,000 people in Guatemala’s department of San Marcos, a state which sits along the western border with Mexico. His brother, wife and baby daughter were also granted temporary humanitarian parole.

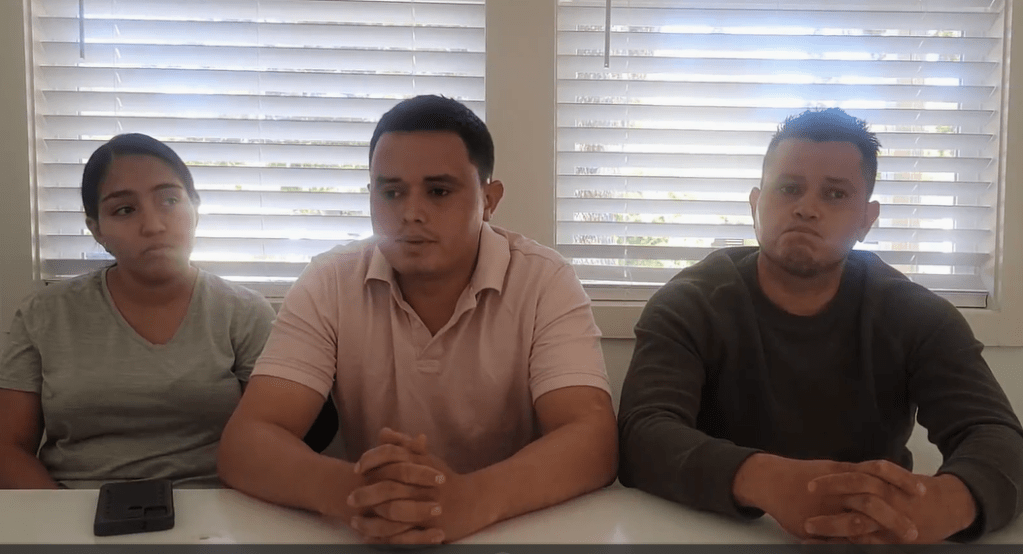

Estuardo and two others – Rubbelsy, 39, a taxi driver, and Enrique, 24, a security guard – crossed the Paso del Norte International Bridge into El Paso in October. They stayed in an El Paso migrant shelter for a few days until their travel could be arranged and are now in other U.S. cities that they asked not be disclosed.

They were among nine Guatemalans injured in the fire and said they, too, feel survivor’s guilt: Of the 40 men who died in the fire, 19 of them were from Guatemala.

Their bodies were flown to their home country on April 11, 2023. Their caskets, blanketed with the country’s white-and-blue flags, lay lined up on an airport tarmac as their families wept over them. The country’s government declared three national days of mourning over the deaths.

‘Their lives have forever changed’

Cristhian and Estuardo are among 50 people – fire survivors and their families – who, with the help of human and migrant rights organizations, received expedited temporary humanitarian parole from the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services.

Entry into the country also automatically put them in the removal proceedings process, which means they still have to go before an immigration judge to present their case, said Jennifer Babaie, director of advocacy and legal services at Las Americas Immigrant Advocacy Center in El Paso-Juárez. In the meantime, they can apply for asylum to remain in the country indefinitely, she said.

Of those 50 who received that parole, 29 were fire survivors – 22 men and seven women. In addition, 21 family members were also granted entry to the U.S., including eight children ages 13 and younger.

None received work authorization, but could apply for it, Babaie said.

Las Americas worked with other human rights and migrant services groups on both sides of the border – including El Paso’s Annunciation House, Derechos Humanos Integrales en Acción (Integral Human Rights in Action) in Juárez and the Instituto para las Mujeres en la Migración (Institute for Women on Migration) in Mexico – to help transfer the survivors and their families into the country.

“Their lives have forever changed after that incident, and they will have a long road to recovery,” said Crystal Sandoval, director of strategic initiatives at Las Americas. Her voice cracked as she recounted some of the struggles the families have had in finding health and mental health care, rehabilitation services and social services to help them survive.

The families are not receiving any assistance from the U.S. government, Sandoval said, instead relying on friends, family, churches, nonprofits and nongovernmental organizations for food, shelter and other basic needs.

The organizations are also representing some of the survivors in pending litigation in Mexico to help them get compensation, Sandoval added.

The Mexican government, through the migration institute, proposed reparations to the victims’ families.

In July, funds of about $200,000 (3.5 million pesos) were approved for each of the families of the 40 men who died in the fire – an amount that human rights groups condemned as vastly inadequate.

Fundación para la Justicia, a human rights organization based in Mexico City, in mid-December issued a statement calling for Mexican authorities to make reparations. “More than monetary compensation, they are in search of justice not just for themselves, but for the thousands who have lost their lives, forgotten at some point in Mexico.”

“The physical wounds are healing, my health is at 30%, but the wounds in the soul, who or how do I heal them? I still wake up in the middle of the night with the fear of being burned alive,” Rubbelsy, the taxi driver from Guatemala, said in a December statement from Fundación para la Justicia. “It is not just about fair reparation for the damage, but about restoring mental health, and having justice.”

Whether any monetary reparations have been made remains unclear, though some payments were discussed during a recent meeting of Mexican government officials.

The executive secretary of Mexico’s National Commission on Human Rights recently told a group of senators that the commission had proof that money had been paid to the families of at least five victims. Francisco Javier Emiliano Estrada Correa, during a Feb. 21 meeting of a work group charged with following up on the incident, counted off the number of families who had received monetary reparations. He abruptly stopped at five and didn’t give further details, saying he would provide the group with a full report on the reparations at a later time.

In its February special report, the commission listed expenses that the immigration institute and other Mexican agencies said they undertook in caring for survivors and their families – including hospital and medical costs, food, travel, hotel stays, laundry services, clothes, disposable cell phones and toiletries.

Mexico also offered the survivors and some of their family members humanitarian visas to remain in the country.

The key to change

Human rights organizations have demanded fair and open trials for the accused, but also accountability and change in INM operations.

Five months after the fire, the migration institute put out a press release stating it planned to close down 33 other provisional migrant detention centers across Mexico and outlined a slew of improvements it promised to make at other stations – including installing emergency exits, smoke detectors and fire extinguishers.

In responding to the National Commission on Human Rights for its report, the migration institute told the organization that six of those provisional centers are still in operation. INM did not make available a list of their locations or that of open permanent centers, the report states.

Among other things, the INM said that in April and May following the fire, 450 INM personnel and others working at migrant detention centers received first aid, fire response and evacuation training.

The INM indicated it installed or conducted maintenance checks on smoke detectors in a number of its properties, and that it installed more than 200 new fire extinguishers on 12 properties and refilled another 1,600 extinguishers across its facilities.

The institute didn’t provide any updates regarding the commission’s recommendation that it create a registry of detainees across centers. It pointed to revised overcrowding protocols that require detention center officials to notify the Immigration Control and Verification Department when they’re at 80% capacity and make plans to decompress them.

The National Migration Institute also didn’t respond to the commission’s inquiry on how many people in each migrant detention center are provided detention cell keys.

This special investigation is a joint project by Cindy Ramirez of El Paso Matters; Rocío Gallegos, Blanca Carmona and Gabriela Minjáres of La Verdad; and Jack Sapoch, Monica C. Camacho and Melissa del Bosque of Lighthouse Reports.

Interested in republishing our special report? You’re welcome to republish this series at no cost. We ask that you please follow our republishing guidelines. For easier access to all the downloadable materials in this project, including stories, videos and photos, contact El Paso Matters’ Assistant Editor Cindy Ramirez at cramirez@elpasomatters.org.

This article first appeared on El Paso Matters and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.