Andy Dewey has been with the Houston Federation of Teachers (HFT) for more than four of its five decades. From the labor stronghold of Buffalo, New York, he’s a lifelong unionist.

“To be a unionist means that you are using your individual voice to add to however many others are right to make improvements over your — not just wages, hours and working conditions — but over your profession as well,” Dewey said. “It’s about the integrity of the profession.”

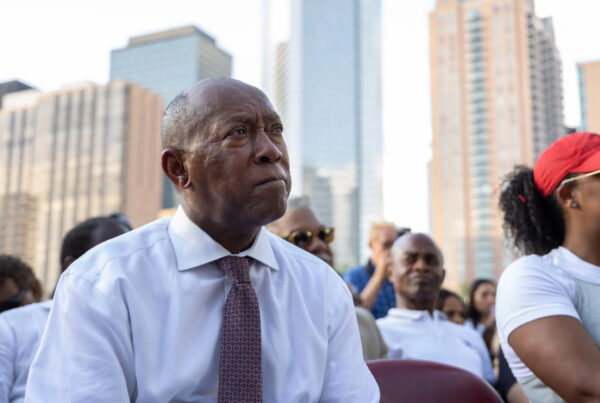

In Texas, teachers’ unions can’t collectively bargain for a contract or go on strike. They can “consult” with district leadership about district policymaking, but in August, the state-appointed leaders of Houston ISD removed HFT as the primary voice for the district’s teachers — even as the union grew by 10 percent in the wake of the takeover to more than 6,000 members, representing over half the district’s teachers. But the loss of consultation and the state’s antagonistic policies towards teachers’ unions haven’t stopped HFT from fighting back.

Since 1973, the union has pushed back on policies they see as unfair through formal grievances and, sometimes, court challenges.

“This was just the way we had to progress, to slowly — I don’t want to say chip away at the authority of the school district; the school district’s administration has authority — but to try to include the employees in some of the decisions that they made,” Dewey said.

The struggle against top-down district leadership continues, this time over some of the reforms implemented by state-appointed superintendent Mike Miles. HFT has filed a steady stream of grievances against various new policies, like strict new bathroom rules for students that teachers are expected to enforce, as well as an open-door rule for classrooms, which was found to clash with safety regulations in certain schools. But HFT’s biggest win so far came just after the start of class, when a legal challenge undercut a key pillar of Miles’ reform plan — for now.