From the Texas Observer:

Frank Pinkard stood before six legislators from the Texas Penitentiary Investigating Committee at the Clemens State Prison Farm in Brazoria County, revealing scars left from 39 lashes. Even after a year and a half, the braided rivulets ran over his thighs and buttocks, rising a centimeter above his skin.

It wasn’t the first time Pinkard had been punished for refusing to work since being convicted 13 years before at age 25. The Black farm laborer from Livingston had been shipped from Huntsville to a railroad camp, then to Rusk and two other prison farms before landing at Clemens, located on former plantation land about 60 miles south of Houston. State prison records show he received a total of at least 82 lashes for infractions like “laziness” and “mutiny.”

On a frigid February morning in 1908, Pinkard, along with eleven others, refused to continue digging a ditch after being forced to wade for days through icy water and mud in the same wet clothes. The warden himself administered the whipping.

“He broke the skin all over me every time he hit me. I bled and my clothes stuck to me for a month,” Pinkard told the six legislators on November 12, 1909.

Barely able to move, Pinkard soon resumed work. “We work as long as we can see how to cut [sugar] cane,” he said. It wasn’t only bucking work that could unleash brutal punishments. Refusing to greet a guard, speaking too loudly, or talking back could result in a lashing or other forms of violence. Every prison laborer who participated in the protest with Pinkard was punished, save one.

Only Alf Reid was spared, having been recently hospitalized after suffering nearly 100 lashes, Pinkard said. Still, Reid died two months later.

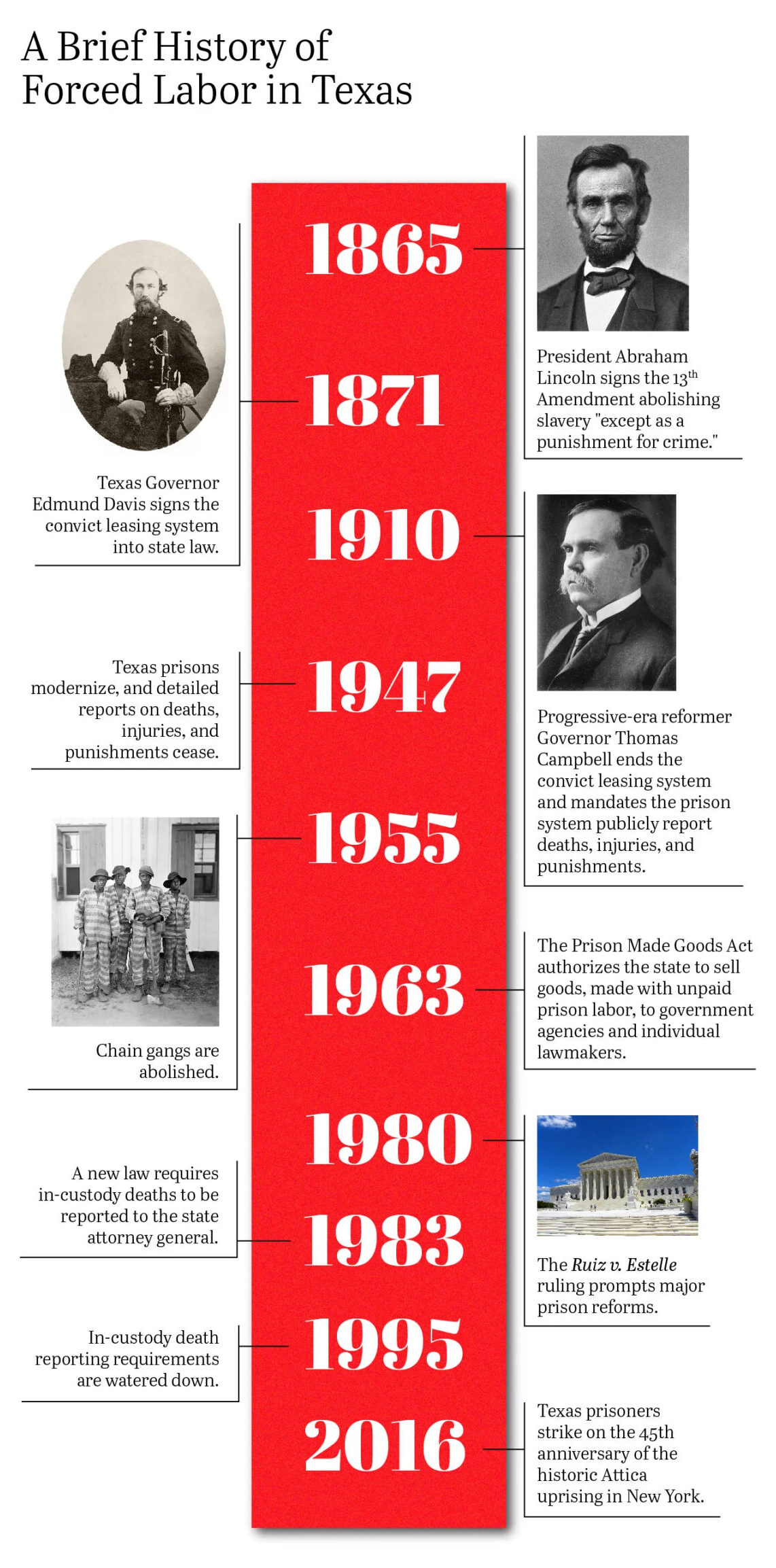

In 1910, members of the Penitentiary Investigating Committee, during the governorship of Thomas Mitchell Campbell, traveled by wagon and train to more than 20 railroad camps, industrial production units, and farms to interview convict laborers, a probe prompted by exposés in the San Antonio Express-News. After the committee released its report in August 1910, the Legislature effectively ended 39 years of convict leasing—a system in which the state hired out incarcerated people as virtual slaves to private contractors.

Instead, the state prison system would put incarcerated people to work on its own farms. Over the next decade, Texas amassed 139,000 acres for prison farms. More than 50,000 acres were purchased from ex-slaveholders who had become convict-leasing profiteers. The state would develop new prison units on these lands to run its own agricultural operations with captive labor. Most of these plantation prisons sprawled across what was known as the “Sugar Bowl District,” the same southeastern counties, including Fort Bend and Brazoria, where most enslaved Texans had been exploited before emancipation.

Today, 24 Texas prison units still have agribusiness operations. Nine are located on former plantations. Incarcerated workers harvest many of the same crops that slaves and later convict laborers did from 1871 to 1910. Like the previous owners, the Texas prison system still compels captive people to work its fields without pay. Guards on horseback monitor those who labor under the sun in fields of cotton and other crops. Texas prisons were finally fully racially desegregated in 1991, but Black Texans still account for one-third of the incarcerated—nearly triple their portion of the general population. Texas is one of only seven U.S. states that pay incarcerated workers nothing. Meanwhile, those incarcerated must pay for many essential items in the commissary. Their unpaid work is mandatory, a practice sanctioned by the U.S. Constitution’s 13th Amendment, which abolished slavery “except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted.”

This prison system of forced work is something of a black box. With free-world labor regulations inapplicable, it’s easy for the state to conceal work-related injuries and even deaths, leaving concerned citizens and journalists to cobble together information from inmate letters, lawsuits, and scant medical documentation. Shockingly, the Texas Legislature required far greater disclosure of work conditions, injuries, deaths, and punishments on prison farms during convict leasing and in the three decades after it was abolished than it does today. To uncover this, the Texas Observer spent months comparing thousands of pages of archived reports and testimonies from the late 1800s to the 1940s to contemporary court filings, state documents, and interviews with incarcerated workers.

After 1946, the prison system’s formerly detailed reports to the Lege abruptly excluded information about work-related injuries and deaths, around the time that Oscar B. Ellis took over as general manager of the system. Ellis served in that role from 1948 to 1961. Historian Robert Perkinson, author of Texas Tough: The Rise of America’s Prison Empire, said Ellis and his successor George Beto, the system director from 1961 to 1971, modernized prisons but demanded high levels of production from incarcerated workers under threat of punishment. Beto boosted profits under reforms that required state agencies to buy prison-made goods. Seeking to further their political careers, they diminished the annual reports to little more than “public relations materials,” boasting of the prison system’s agricultural and industrial output without mentioning its workers, Perkinson told the Observer.

Historic and modern statistics show that the death rates of the incarcerated remain similar to those reported to the Legislature nearly 80 years ago. At a rate of 4.7 out of 1,000 incarcerated people, the 2023 death rate in Texas prisons was only slightly lower than it was in 1946, when those detailed legislative reports ended. Out of a prison population of around 120,000, the Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ) recorded 574 total prisoner deaths last year. In 1946, 22 out of 4,246 prisoners died in custody—a rate of 5.2 in 1,000. Harsher sentencing laws and an aging prison population may impact modern death rates, but criminal justice experts say the present lack of transparency makes it hard to discern the causes of the troubling frequency of prisoner deaths.

Since 1983, prison and jail officials have been required to report basic information on in-custody deaths to the Texas attorney general. Failing to report them is a misdemeanor. Compliance improved when those reports became public online, but they still contain scant details on the circumstances of death, making it difficult or impossible to figure out if fatalities were related to avoidable workplace injuries, heat exposure, or excessive punishments.

Library of Congress, Creative CommonsTDCJ officials today routinely cite incarcerated persons’ privacy as a reason to provide minimal information on in-custody deaths or injuries. The agency did not allow the Observer access to prison farms for this story and refused to disclose individual prison work assignments. TDCJ also denied requests for information related to disciplinary proceedings or alleged prisoner abuse. A TDCJ official said disciplinary information can only be released in very limited circumstances.

Michele Deitch, director of the Prison and Jail Innovation Lab at the University of Texas at Austin, told the Observer that today’s dearth of reporting requirements reflects a current criminal justice culture that is “punitive [and] secretive about what’s happening inside our facilities.” Deitch’s own research confirms the state supplies little to no information to the public on prisoner treatment or conditions. “The data that is required to be kept by statute doesn’t go into issues of safety or health,” she said. “It goes into things like how many people are incarcerated or parole rates or how much things cost. … It’s not providing us with a window into what’s happening.”

State prison officials today appear to have massively underreported the number of recent deaths related to heat, according to interviews, public health research, and lawsuits. Even in the free world, Texas workers die of heat exposure with disturbing regularity, a problem exacerbated by the climate crisis. Heat deaths are often missed—or concealed—if no one records a body temperature reading soon after death. TDCJ’s reports to the attorney general do not require such readings.

A TDCJ spokesperson told the Observer in April that there had been no heat deaths across the state’s approximately 100 prison facilities for a dozen years. That same month, a Texas prisoner and several advocacy groups alleged in a lawsuit that hundreds of people got sick and at least 40 people died of heat-related causes in TDCJ custody in 2023 alone.

Tommy McCullough, 35, died on June 23, 2023, of what the lawsuit said was heat-related causes. He got up to report to work and collapsed—temperatures in Huntsville’s Goree Unit reached 130 degrees Fahrenheit that day. (An autopsy report, obtained after original publication of this story, identified toxic levels of methamphetamines as the cause of McCullough’s death. Such a finding does not necessarily rule out hyperthermia.) Separate Texas Department of Insurance data obtained by the Observer shows that at least nine TDCJ prison employees reported injuries caused by extreme heat in 2023 that caused them to miss work.

Even though prison work requirements were supposedly narrowed in 1999 to only apply to those “physically and mentally capable of working,” incarcerated Texans still report that TDCJ officials put them to work regardless of health or physical conditions. In 2019, Jack Gutierrez, a 42-year-old incarcerated at the Terrell Unit, sued prison officials, alleging they refused to let people assigned to the cannery change jobs, even when a doctor had recommended the switch. Gutierrez alleged he and other men were told they had to work six months to a year before being considered for any transfer. That same year, another Texas prisoner filed a lawsuit alleging staffers at the Darrington Unit sent men to work without water for six days.

A TDCJ spokesperson told the Observer that prison officials follow doctor recommendations regarding work assignments and that “All inmates have access to water at all times.”

Operating a system of forced unpaid labor without strict reporting requirements appears to have allowed the prison system to perpetuate working conditions that still too often threaten incarcerated workers’ health and lives. Some advocates compare it to slave labor on some of the same land 200 years ago.

State Representative Carl Sherman, a Democrat from DeSoto who serves on the Texas House Corrections Committee, told the Observer: “Individuals who are incarcerated [are] being guarded by people who are wearing the same color clothing as during the Confederacy. The South really did not lose when it came to maintaining this form of free labor.”

•

In 2019, Alex Zuniga was housed in an isolation unit, known as “administrative segregation,” at the Darrington Unit (later renamed Memorial Unit). The land the prison sits on was once owned by Abner Jackson, Brazoria County’s second-largest slave owner, who divided more than 300 enslaved people between three properties. The Retrieve Unit, another TDCJ prison, later named the Wayne Scott Unit, also sits on land once owned by Jackson.

Typically, the incarcerated in solitary are kept in one-person cells for most of the day, but Zuniga said prison officials let him and the other men out a few days a week to do agricultural work. The first time he walked through the unit’s chicken house, he threw up, overwhelmed by the smell and cacophony of 80,000 birds in an enclosed space. (A TDCJ official told the Observer that prisoners in solitary are not allowed out to work.)

On a typical day, Zuniga, who is Mexican-American, said he would join a crew of about 50 others required to turn out for work around 7 a.m. “It’s kind of spooky because in the morning, you have a little bit of mist, and you have to wait for all that to clear out before you can step onto the farm,” Zuniga said. The men would be strip-searched, then walked or driven in wagons to their work area, where they would stand in a line in pairs and begin to clear out weeds with hoes or by hand.

To set the tempo for hoeing, one worker would call out, “Rock on it one, rock on it two, rock on it three.” After three swings, all the men stepped forward, and the hoes whistled through the air again.

Field workers for TDCJ still have the same basic marching orders as their predecessors: Work hard without pay for the benefit of the prison. Mostly men of color, in matching uniforms, still toil in fields producing tens of millions of pounds of crops, including raw cotton that the prison then turns into shirts, pants, underwear, and towels. Guards on horseback monitor them, and dogs are sent to track anyone who tries to escape.

During the convict-leasing era, white men were mostly sent to railroad camps or stayed in the Huntsville Unit known as “the Walls.” Black men, who were often convicted for petty crimes like mule or horse theft, were typically delivered to the sites of former plantations to work. In an 1874 convict camp report on the Lake Jackson Plantation, Inspector J.K.P. Campbell wrote that incarcerated African Americans were “unfit for any other pursuit” than farming. Thus, like their ancestors, Black captive laborers cultivated and harvested sugarcane and cotton on former slaveholders’ land under management systems similar to slavery.

Testifying to the Penitentiary Investigating Committee in 1910, John Lenz, one of few Black men locked up in the Walls before being transferred to Clemens farm in Brazoria County, stated that the industrial work assigned to white people in Huntsville was much less dangerous than what Black workers did on prison farms: “Give me 20 years solid here before I would get six months on the farm. I would be a dead man.”

The call to end convict leasing came in the Progressive Era of the early 1900s, when reformers targeted corruption and pushed to modernize many aspects of American society. Surprisingly, some segregationist Democrats in Texas played key roles in the reforms.

In 1906, when Thomas Campbell gave his first campaign speech as a Progressive-era Democratic candidate for Texas governor, he railed against “those who would debauch popular government and make it the instrument of avarice and greed.” A former Confederate Army captain and court-appointed manager of a bankrupt railroad, Campbell distrusted monopolies and sympathized with unions. He supported segregation in prison and elsewhere but opposed the use of the incarcerated “to enrich individuals and corporations.”

Under reforms Campbell promoted after becoming governor, convict leasing ceased. Texas’ incarcerated population remained unpaid for work, but their working conditions were recorded and publicized in detailed legislative reports. As part of the push for greater accountability and transparency, state law required “at the end of each month reports showing fully the conditions and treatment of the prisoners,” a requirement that remained effective through the 1940s.

Farmworkers made up half of the prison labor force throughout most of the 19th century. From 1900, that figure rose to at least three-quarters until prison manufacturing expanded in the 1960s.

From 1947 to 1983, very little information on prison deaths was disclosed. Then in 1983, Walter Martinez, a Democratic member of the Legislature from San Antonio, ended what he called a dark period in prison history by spearheading a new state law that required prompt reporting of all deaths of people in jails, prisons, and law enforcement custody. All agencies had to report any death within 30 days to the state attorney general’s office. But for decades compliance with the law was spotty.