Holiday traditions can so quickly become ingrained that we don’t even question where they came from. Take, for example, decorating with poinsettias.

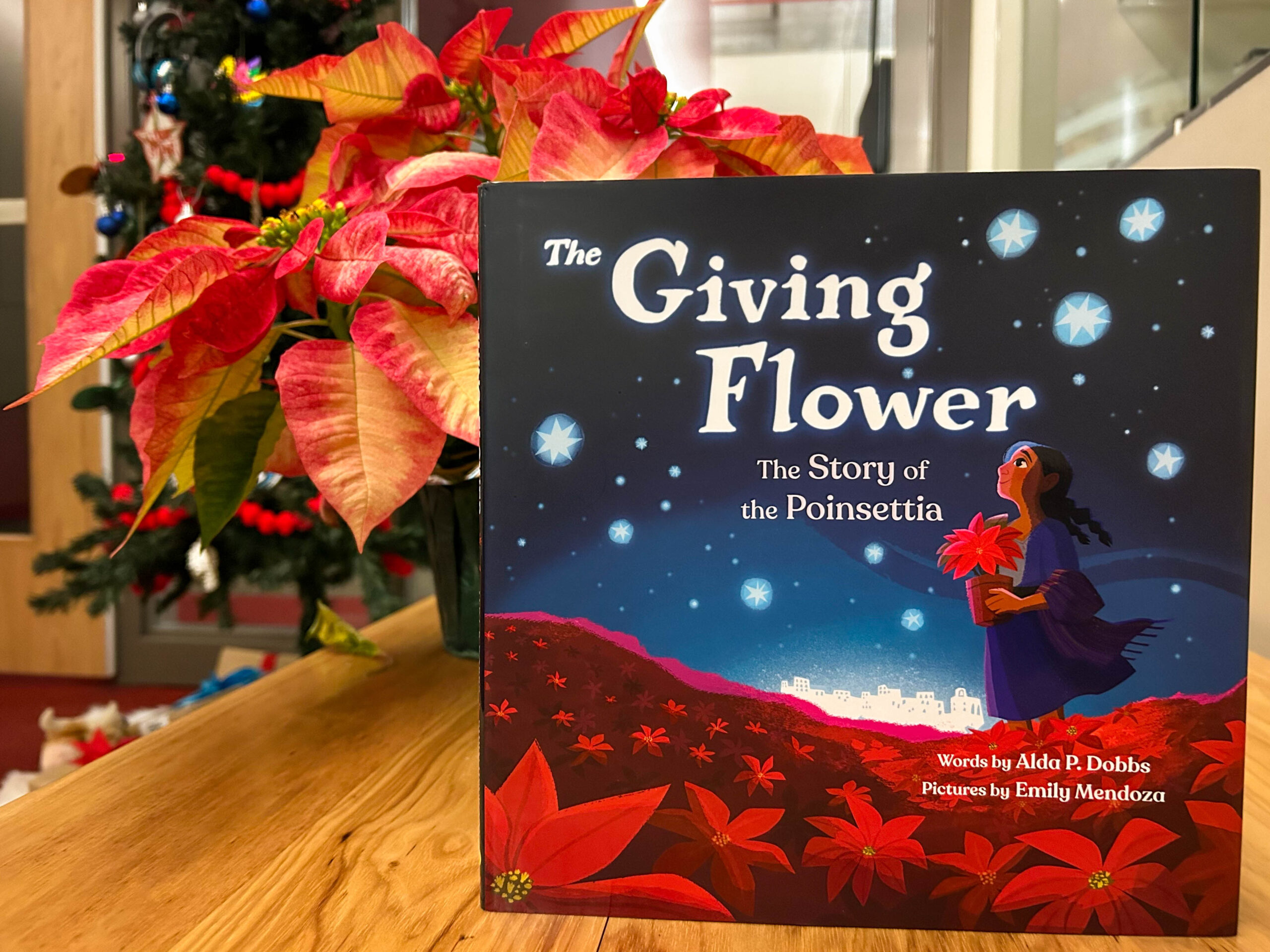

Houston-area author Alda P. Dobbs traces the history of the Christmas flower in a new children’s book, “The Giving Flower.” It’s published in both English and in Spanish.

She joined the Standard to talk about the new book. Listen to the interview above or read the transcript below.

This transcript has been edited lightly for clarity:

Texas Standard: What made you want to tell this story?

Alda P. Dobbs: In my writing, ever since my the first book I published, “Barefoot Dreams of Petra Luna,” I’m always trying to make connections between cultures and and different countries. And I was born in Mexico myself and moved to the United States when I was a baby and grew up in San Antonio.

But ever since that age, I’m always trying to make a connection to Mexico and then to the U.S. And every country I’ve traveled to, the same thing. I’m always finding those connections.

And when I saw the Poinsettia sitting next to me during a car rider line when I was picking up my kids, I started thinking about where that flower comes from. And yeah, that’s how the the book came out about.

So what surprised you as you dug in?

What surprised me the most, because I knew it had to do something with Mexico. I knew the flower’s from Mexico, but I didn’t realize that it was the Aztecs, the Nahuas, the ancient Nahuas that had discovered the flower. They’re the ones who saw it in the wild and captured that beauty and cultivated it, made it flourish to serve people and stuff like that.

So that was the beginning of that flower and it’s just fascinating to see how that flower has come through the ages.

I think one thing that surprised me is I thought “red flower.” But even right there I’m not exactly accurate, am I? The red isn’t even the flower – that’s part of the leaves, is that right?

That’s true, that’s right. And I give a presentation on the book to children. I explained that, you know, that that’s one of the first things we covered, the fact that what we consider petals, right?

The red long broad petals… They’re actually not petals, they’re modified leaves called bracts. And I make them pronounce the word “bracts,” and it stays in their mind that those are the bracts, and the actual flowers are the ones right in the center. There are a bunch of them.

They’re clustered in the center of the bracts. And they’re so tiny that pollinators wouldn’t be able to see them because they’re so small. So you need these big, bright red bracts to bring the attention of the pollinators to come to those tiny little flowers.

Wow. You know, you use this device in this story of repeating the phrase, “you just wait and see.” Why did that feel like the right way to tell this story?

I think my aim is for children to yes, so that they know all the potential they have – just like the flower had all this potential. And, you know, things happen, things flourish with time and for them to have that as well, that knowing that they, too, can flourish, given time.

Well, because of the Mexican roots here, it seems very natural for you to have also done a Spanish edition. When you’re working, I mean, is that an extra challenge to get a publisher to sign on to something like that? Or how does that work?

Being a native speaker, a Spanish native speaker, you know, they said, “Hey, do you want to do the translation? And I happily accepted. And I thought it was gonna be easy, being, like I said, a native speaker, but it turned out to be more challenging.

And the way I explain it to people and especially children, just showing the body parts, basic body parts in English – like head, knee, toe, back – there’s small, one-syllable words, but if you translate ’em into Spanish, they’re three, four-syllable words that get long and it’s a challenge being able to think in a different way to make words flow.

Tell me about your illustrator because for a children’s book, I think that’s so important for them just to be able to experience the story through pictures.

Yes. Oh my goodness. I was so lucky to have Emily Mendoza. They hired her for the illustrations and she did an amazing job.

I think she captured everything I was hoping for and beyond, just because when I was blown away by by the colors, the vivid colors and the way she captured the small town in Mexico, in Guerrero – the village itself, the spread where it shows the village is just amazing.

What do you hope for this book?

I’m hoping that it’ll inspire curiosity in people, that people will become curious as to where things come from, right? Something ordinary, something we see every year, every season that we take for granted – to pause for that second, that moment and see where the origins are, where they’re from how did it come about and all the people that contributed to that, all the silent voices behind that object so that we could appreciate things more.

And also there was those connections that we realize, oh, you know, it comes from here, I’m from here, or look, it’s similar to this… And just create those connections.

What have you heard from children as you’ve been traveling Texas and sharing this story?

They’re amazed just by the origins, just how much the flower has changed. You know, at one point the the bracts, the big, red broad bracts, they were smaller, they’re narrower and more scattered around the flower when it was in the wild.

And the plant also grew 10 to 15 feet tall, you know, the bush. It was in these short, nice little compact flowers that we have now that we see at the supermarket. And for children, it amazes them how the change in these flowers and again, how science contributed to that.

Yeah, the cultivation and I guess the investment in some aspects to favor these broader flowers that we’ve come to favor, right?

Exactly, yeah. The science and also just Mother Nature, ’cause ultimately it’s Mother Nature who comes up with these amazing patterns and colors that then scientists are able to extract and produce and just to show the beauty of mother nature within the flower.

What fascinates me, too, is sort of the, I guess, advertisement of the poinsettia as a Christmas flower. It really was sort of these American entrepreneurs that put it in the right place that made us all think, “Oh, yeah, poinsettias, they’ve just been around forever. They are part of Christmas,” right?

Exactly, yeah. It’s amazing the timing, too, when the poinsettia became the size and, like I said, the the broader bract and whatnot, how color T V in the 1950s started coming about and they took advantage of that, that those two venues intersected and it just flourished into the “okay, this is one way to promote it – tie it into Christmas.”

But yeah, you have the story of Pepita who’s been tying it to Christmas since back then, since when the Spanish were in Mexico. They just brought it to TV and spread it everywhere.