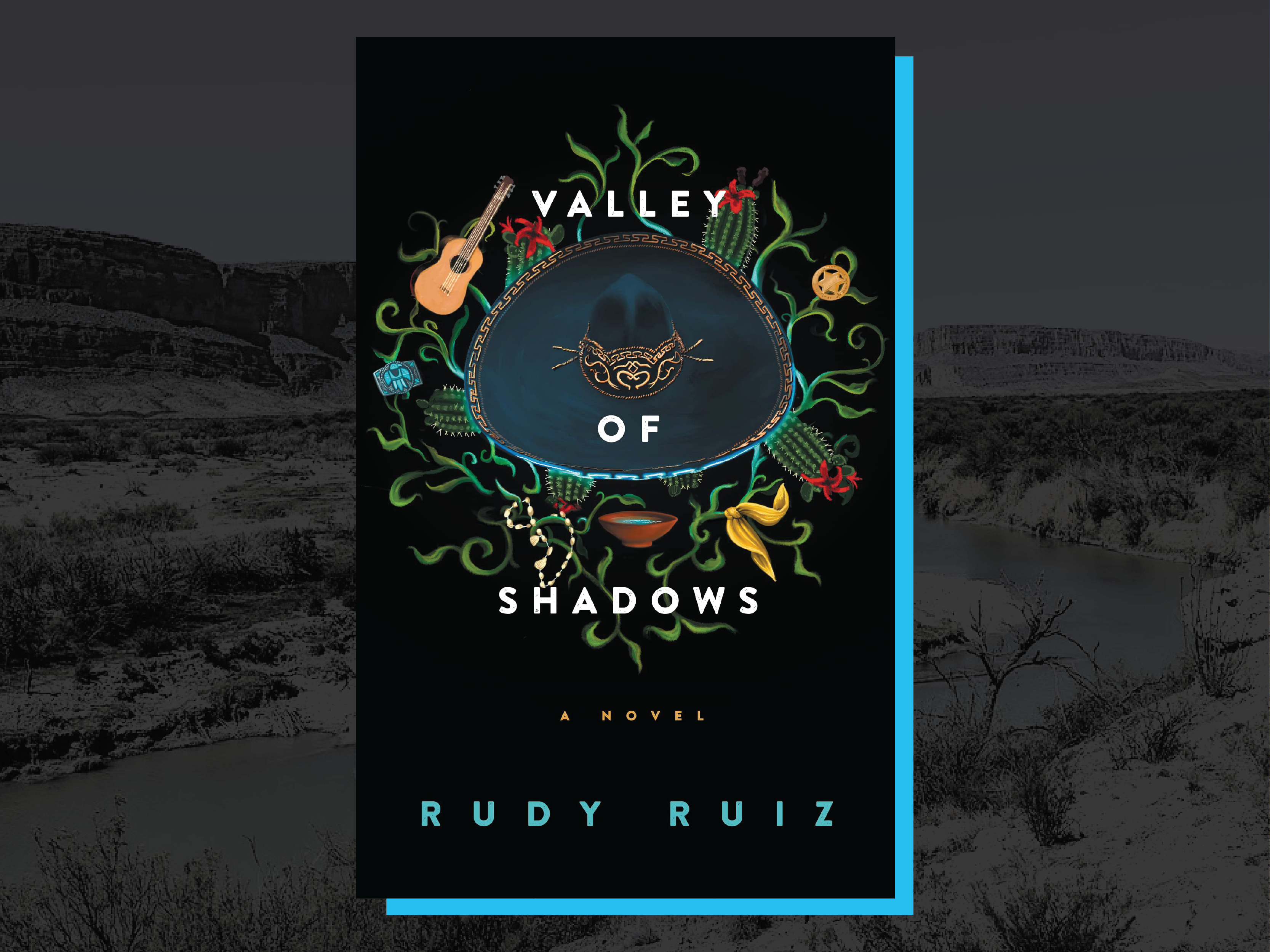

Along the Rio Grande in the early days of Texas, a man loses his family when the river shifts course. This catalyst kicks off a new take on the classic Western tale, one filled with magic realism and the supernatural.

It’s a novel by award winning author and San Antonio resident Rudy Ruiz, called “Valley of Shadows.” It’s the winner of the Texas Institute of Letters’ Jesse H. Jones Award for Best Work of Fiction and one of the featured works at the upcoming Texas Book Festival, which runs Nov. 11-12.

The Standard spoke with Ruiz on the book and its connections to the Rio Grande Valley both in fiction and real life. Listen to the interview above or read the transcript below.

This transcript has been edited lightly for clarity:

Texas Standard: Congratulations on all the success. I have to ask about the inspiration. You grew up in in the border region?

Rudy Ruiz: Yes, I grew up down in the Rio Grande Valley. Born and raised in Brownsville, Texas, and spent quite a bit of time on both sides of the border growing up, as my mom was from the Mexican side of the border, from Matamoros.

Wow. Well, did you know someone like your main protagonist here, Solitario Cisneros?

You know, I definitely felt like I did.

I grew up very much under the influence of my father, who was first generation born on the U.S. side of the Rio Grande. And he raised me loving to watch the old Western movies, like the John Wayne-type of movies. But he also raised me watching a lot of the old Mexican charro movies, like starring people like Pedro Infante and Jorge Negrete.

And so I dreamt of kind of creating a hybrid of that. I wanted to kind of reimagine the Western narrative with a Mexican American as the hero and also with indigenous people as people in heroic positions within the narrative.

I love this element of the river running where it will, and this affects profoundly Solitario’s life and becomes a kind of fulcrum for the story, really. Did you hear of those kinds of stories when you lived in Brownsville?

I did. My family’s, you know, lived in the area since the 1700s. And, you know, we’re among the original families that settled what this present day Matamoros/Brownsville.

So I heard stories from my family – my father and my grandparents – about the river shifting course back in the mid-1800s. You know, hurricanes would come in as they still do, but back then, the river was not controlled via dams as it is today. So after massive flooding and shifting of the landscape, the river sometimes just changed course. And once the river became the border, you know, this really had like a massive impact on obviously people’s land, their property, roads, what country they were in.

And that’s kind of what happens in the “Valley of Shadows.” And I kind of wanted to explore that because I feel like it’s a symbol of how borders are arbitrary and manmade and where sometimes, you know, allowing humanity to be at the whim of these sort of intellectual constructs that the climate and nature can change also, you know, at its own whim.

» MORE BOOK FEST PICKS: ‘If somebody is in trouble, you help’: Author Luis Alberto Urrea recounts his mother’s WWII story in new novel

You know, the setting is so stirring and the prose, frankly, so riveting and beautiful that I think in a way, someone just hearing about this book probably just wants to know, well, what’s the through line of the story? We have to talk about that. Solitario Cisneros, he is sort of stranded, in a sense, on the Texas side when the river moves and he retires his gun and badge – a law man, once upon a time – and he sort of spends his time hiding out on his ranch, I suppose. But then something happens – murders, kidnappings in the town – and he feels compelled to confront this somehow.

Yes. You know, the story of Solitario is a story of a person who is really battling a family curse and all the men in his family are haunted by it.

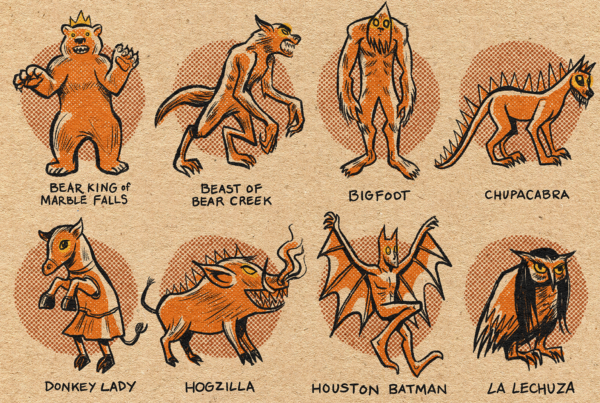

And, you know, due to that curse, which is really a symbol of multi-generational trauma that a lot of families carry within themselves from generation to generation, he has really found himself, you know, having lost everything – his country, his beloved wife, his job – and yet he spends his time out on the ranch in West Texas, basically hiding out and communing with spirits, which is one of his abilities. And that’s where the magical realism comes in.

But when the town is threatened by the series of gruesome crimes and the town, which is made up of Anglo settlers which have come in to build after the place has been stranded on the northern side of the river – so it’s made up of Anglo settlers, the original Mexican settlers, the more original indigenous people that lived there – the town becomes a tinderbox.

So Solitario really comes out to face his demons and help solve these crimes, because he sees that if he doesn’t, the whole town and the people he does still care about could just explode.

Could you say more about the person that becomes Solitario’s source of inspiration and support? An Apache Mexican seer, right?

Yes. Onawa is his friend and partner in solving the mysteries. And this character really grew as I wrote the book. But she became a big part of his story of healing because he’s a person who’s really overcome by grief and mourning for the wife that he lost. And now it sort of helps him not only confront the evil that is threatening the town, but also open up his own heart to the possibilities of living again and allowing himself to love and to feel for others.

You know, I think that this reaches out across all sorts of borders, not just to Texas, but clearly very much a book about what we mean when we talk about a sense of place or what we mean when we talk about even our own identities and how much externalities and our own internal struggles can affect that perception. Would you say that’s fair?

Yes, absolutely.

You know, when I was writing the book, I was very swept away by the landscape of West Texas. You know, being out and spending time in Big Bend, you know, out there around Marfa, these vast open spaces that they kind of haunt you and they speak to you. And when you’re out there in nature, you know, and the stillness of it, you just feel close to something greater than yourself.

It also makes you see the world in a different perspective. And and so it really made me think of my own experience growing up in the Rio Grande Valley, as how much you can belong to a place, as much as a place can belong to you. And that no matter what people say about, you know, the border or the official nationhood and those types of political issues, a sense of place and culture and belonging kind of runs deeper and in a way transcends those political ideas.

It seems like you’re really committed to this idea of telling multicultural stories that sort of transcend any single sense of culture.

Yeah, I love that. You know, growing up on the border, I crossed the river almost on a daily basis to see family in Mexico and spent time with my grandparents there. And when I was growing up, when we thought about the border in the 1980s, it was really about building bridges.

And that’s kind of how I saw it when I left the Valley, was I wanted to take that experience and always try to work on ways to build bridges between people of different cultures, different languages, from different countries. And that’s what I try to do in my in my writing.

And I think, you know, when you look at the state of our country and really the state of the world, I mean, it seems to me like that’s what we need most. You know, we need to figure out ways to stop hating each other, stop fighting each other, and start working together to make the world a better place for the next generation, for our kids and for everyone.