This story is part of our coverage featuring the authors making an appearance at the upcoming Texas Book Festival, which runs Nov. 11-12.

When the United States entered World War II in December of 1941, every aspect of life on the home front changed for women.

The war brought new opportunities to work outside the home — or to work for higher pay. Women got jobs in factories and shipyards and took municipal jobs left vacant by men.

A few hundred thousand women also served in their own branches of the armed forces. But those weren’t the only women on the war front. Women who volunteered with the Red Cross were also sent to the European theater.

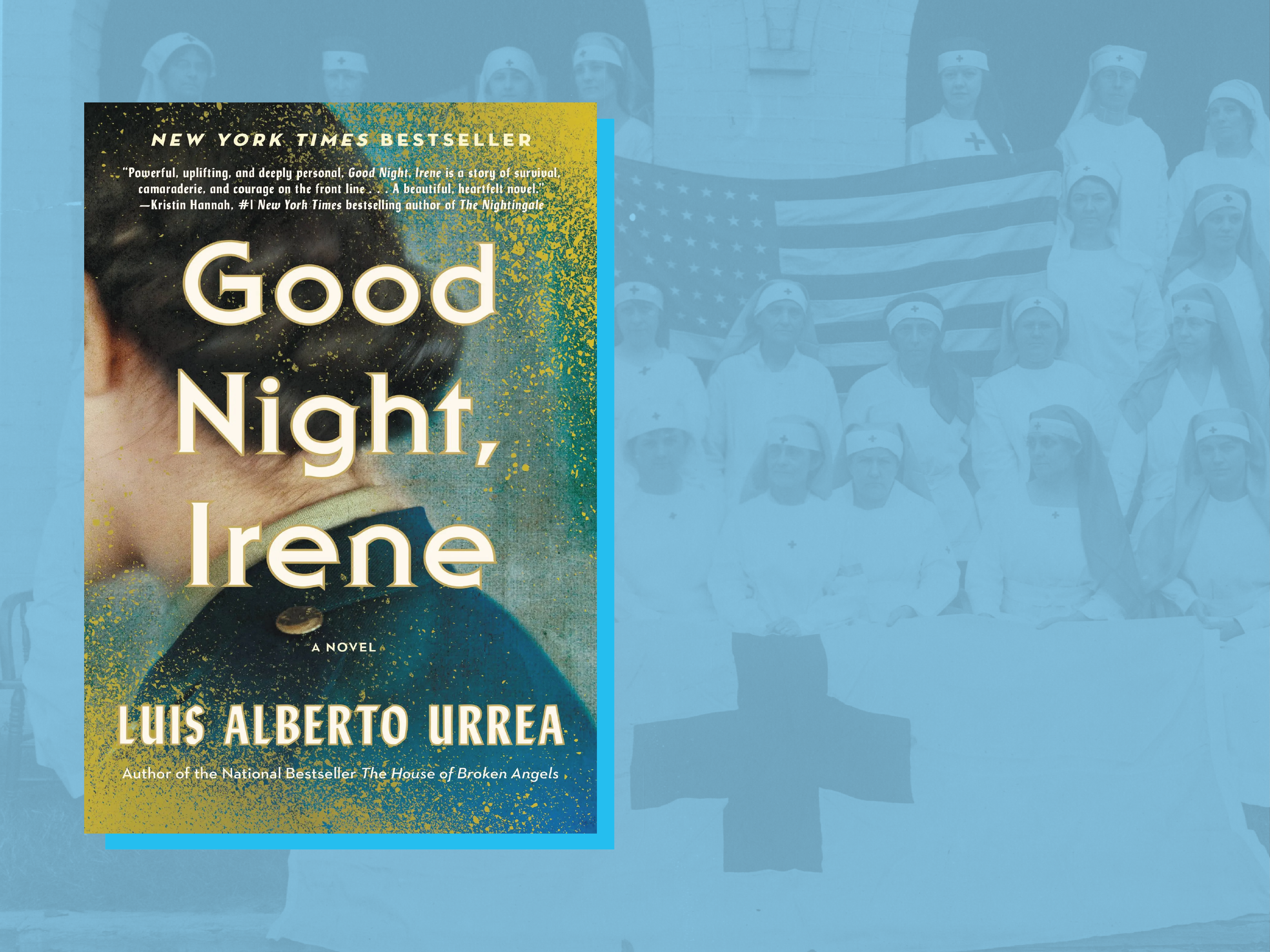

The new novel “Good Night, Irene“ follows Irene Woodward in 1943 as she abandons an abusive fiancé in New York to enlist with the Red Cross. During the book, Irene experiences some of the biggest battles of the war.

Author Luis Alberto Urrea said officially these women were called the Club Mobile Corps. In the common parlance, they were often called “donut dollies.”

“The Red Cross women who served soldiers served in clubs to the rear where they gave them coffee, donuts, played cards with them… just morale boosting. And some of the people involved, including Gen. Eisenhower, got the idea that it might be interesting to put them on trucks, make it mobile,” Urrea said. “And they drove ultimately into combat — unexpectedly, I think. They were at the front.”

Urrea said he was inspired to write the book based on the experiences his mom had in the Red Cross during the war.

“Everything that happens in the book to the character of Irene is actually chronologically the things my mother survived. And almost didn’t at the end,” he said. “She was carrying around a lot of shadow. You know, when you’re a kid, you get into things you’re not supposed to get into. So I opened up her Army foot locker and I found all of her stuff. But one of the things I found was photographs of the victims of Buchenwald. That was the shocker. You think, ‘wait, that’s my mom. But what is she doing in this?’”

Urrea said his mom was always reluctant to talk about her experiences. However, he felt it was important to tell this story given how little is out there about the role the Red Cross women played in the war.

“The records building that held all of their information burned down,” he said. “I think in 1970 or 1971. So they were officially lost. There’s very little record of those women.”

Urrea used his mother’s material as well as interviews with her best friend from the war and additional research to craft his story.

“Her truck driver, the woman who becomes Dorothy in fiction, her best friend from the war, we thought she was dead. But she lived about 80 minutes from our door here in Illinois, and we didn’t know it,” he said. “She was 94 when we met her, and she was quite the firecracker even at 94. I mean, I’ve never known anybody like her. Her name was Jill, and we were friends with her until she passed away at 102.”

Urrea said writing about his mother’s experience made him think about the ties that bind us.

“I think one of the incredible lessons for me, which I think are pertinent to all of our culture right now in such upheaval, is that you don’t want to forget what makes us Americans, whatever that mysterious thing is,” he said. “There’s a moment in the novel which really happened to my mother when she was severely wounded. She was at the bottom of a mountain, dying, and GIs climbed in the middle of the night down the mountain, and they attended to her wounds and they had to get her out and they had to climb the mountain. And so they took off their shirts and made slings and then wore her on their backs and climbed the mountain.”

The soldiers ended up hiking six miles with Urrea’s mother strapped to their back to get her to a medical unit.

“To me, was such a stirring definition of being an American. They didn’t ask her what her politics were, you know? She was in trouble and they helped her, at risk to their own lives,” he said.” And that moved me so much. The more I thought about it, the more I thought, ‘yeah, this is us, isn’t it?’ You want to think that if somebody is in trouble, you help.”