From the American Homefront Project:

During the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the military used open air burn pits to get rid of garbage. Plastics, metal, even biohazardous waste were doused in jet fuel and set on fire.

Millions of service members inhaled the noxious fumes, including Chad Lennon. Today, he’s a major in the Marine Corps Reserves. But for seven months in 2010, he served in Afghanistan, where he said he often slept near the black plumes of smoke rising from the pit.

“You name it, it was in there,” Lennon said about the burning pit of trash. “Electronics, paper, wag bags which are the bags everyone pees and poops in. I wouldn’t even be surprised if there was body parts thrown in there.”

At his doctor’s office on Long Island, New York, Lennon recalled he began to experience odd physical symptoms – like shortness of breath and tightness in his chest – that the life-long runner hadn’t experienced before. It got progressively worse.

“I’d get sick for three months straight essentially,” Lennon said. “It would start around September, from a cold to a sinus infection to the flu to bronchitis, and it was just constant. And I’m like, ‘I don’t understand what’s going on.’”

Lennon blames his symptoms on his burn pit exposure. The Department of Veterans Affairs links burn pits to a variety of health conditions, including several forms of cancer, asthma, emphysema, and sarcoidosis.

Now, Lennon and other veterans are enrolled in a new long term study to remotely collect real time data on their health, such as heart rate and EKG’s, and to create new screening tools for veterans who get health care from private doctors instead of the VA.

Northwell Health pulmonologist Anthony Szema hopes to build a better understanding of long-term burn pit exposure.

Northwell Health

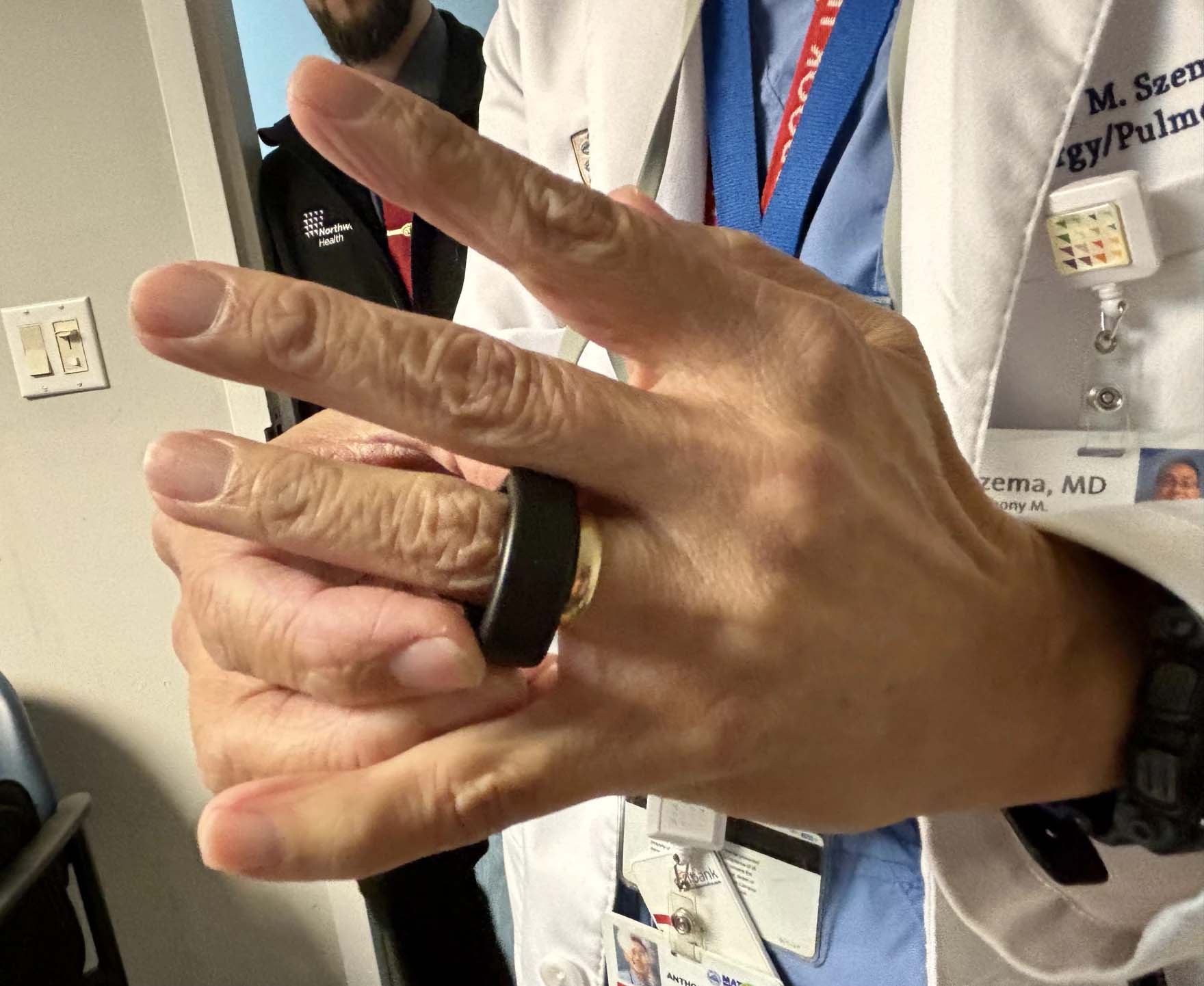

Through artificial intelligence and a finger-worn monitor, researchers hope to collect health data over several years so they can learn more about burn pit exposure and develop new tests and treatments.

“Technology allows us to remotely monitor patients,” said Dr. Anthony Szema, the pulmonologist leading the study through Northwell Health, one of the largest health systems in New York.

“We can stick a ring on somebody’s finger, it goes to their phone, the veteran can look at their oxygen saturation and heart rate because it’s a continuous pulse oximeter,” he said.

For example, if the ring detects symptoms of a panic attack, the app can alert the wearer and prompt them to fill out a specialized survey about the real-world stimuli they’re experiencing.

“This is actually big data artificial intelligence,” Szema said. “Because if we’re taking readings every five seconds for the next two years, that’s a lot of information, then we can cross correlate it.”

Szema said he hopes the real-time monitoring and standardized screening questionnaires will help define what veterans often report as vague, hard-to-explain symptoms.

“They’ll say, ‘I just don’t feel right,’ and all the breathing tests are normal,” Szema said about respiratory injuries with subtle symptoms. “The chest x-rays and the CAT scans are normal.”

The results of the study over time will add to a growing body of research about the impacts of toxic exposure from burn pits and could lead to new diagnostic tools for lung diseases.

In a 2004 photo, Army Sgt. Richard Ganske uses a bulldozer to maneuver trash into a burn pit in Balad, Iraq. Burn pits were common at U.S. military outposts in Iraq and Afghanistan, where troops incinerated tons of waste every day.

Abel Trevino / U.S. Army

Just like the herbicide Agent Orange caused a slew of health problems for Vietnam War veterans, Szema predicted that diseases from burn pit exposure will continue to plague the veterans from Iraq and Afghanistan.

“This was such a long war, longer than World War II and Vietnam,” Szema said. “There’s so many more people, it’s going to affect a larger portion of veterans, and the exposure was so long.”

Lennon, the Marine reservist, said he’s participating in the study now because he’s worried about his future and wants to be proactive.

“I’m trying to do whatever I can,” the parent of two said. “I know my wife’s concerned. And especially with the guys I served with, who are young and dying of cancer, you just hear about this all the time.”

In 2022, the PACT Act became law, making it easier for veterans who became sick from burn pit exposure to get health and disability benefits from the VA. About 3.5 million veterans could be eligible. Doctors like Anthony Szema are still investigating what long term effects might be in store for this latest cohort of war fighters.

This story was produced by the American Homefront Project, a public media collaboration that reports on American military life and veterans.