Driving west out of Marfa, you pass a foreboding sign. “No service next 74 miles.” You won’t see much on that stretch of highway 90. But past the small town of Valentine, population 134, there’s a place where the mountains stand guard over a row of desert-worn, derelict buildings. There’s a rundown four-room hotel and a boarded-up gas station. It’s all covered in overgrown brush. This is Lobo.

Even in its heyday, Lobo was never home to more than 100 people.

If you ask Jon Johnson about growing up there in the late 1950s and 1960s – what he did for fun – he laughs. For kicks, he says, he would leave -– drive up and down the highway with friends.

In the shadows of the Sierra Vieja and Chispa mountains, the teens would park their cars in a semi–circle and turn their radios to the same Oklahoma City radio station

“When you had all those cars parked on that little flat like that, with all the radios going and the full site of the stars and the heavens up above and that music playing — you’d fall in love,” says Johnson, who spent the majority of his teenage years in Lobo.

Johnson’s family farmed around Lobo, but those acres and acres of fields are gone. It’s a bit unfamiliar to Johnson now, who’s hiking through the Lobo Flats with his dog Stella on a quiet October afternoon. As he’s working his way through waist-high brush, walking sticks in hand, Stella comes across a ditch filled with water. “How about that,” says Johnson, surprised. “I didn’t know this was down here.”

Water plays a key role in the rise and fall of Lobo. It started in the late 1800s with the San Antonio to San Diego rail Line.

“They had to water those locomotives, ‘cause they’re steam locomotives and they had to have coal,” says Larry Francell, former director of the Museum of the Big Bend.

Francell says railroad companies sold the land nearby for profit and to create infrastructure they could rely on. Several far west Texas towns were born this way. In Lobo, the rail company even set up a small, four-room hotel. These companies, says Francell, “laid out these places that they called towns or established names and hoped people would go there.”

Now the lure of Lobo wasn’t the land itself, but what was under it: lots of water. In the early 1900s, Lobo saw a flash of popularity, but it wasn’t until the mid-20th century when the small town saw its most sustained activity. In the 1940s hopeful ranchers and farmers flocked to the area, hoping to make a living in the fertile desert oasis. Johnson’s father was one of them.

“We grew tomatoes, we grew beans, we grew onions one year,” says Johnson, sitting on a small rise in the Lobo flats that overlooks the land his parents farmed on.

“Our onions used to go to New York City, they were gourmet. They were really big and sweet,” he adds.

Johnson says the soil in the flats is rich and all you need to grow “beautiful crops” is water.

So his dad, he says, drilled a 1,000-foot well to irrigate their 250 acres.

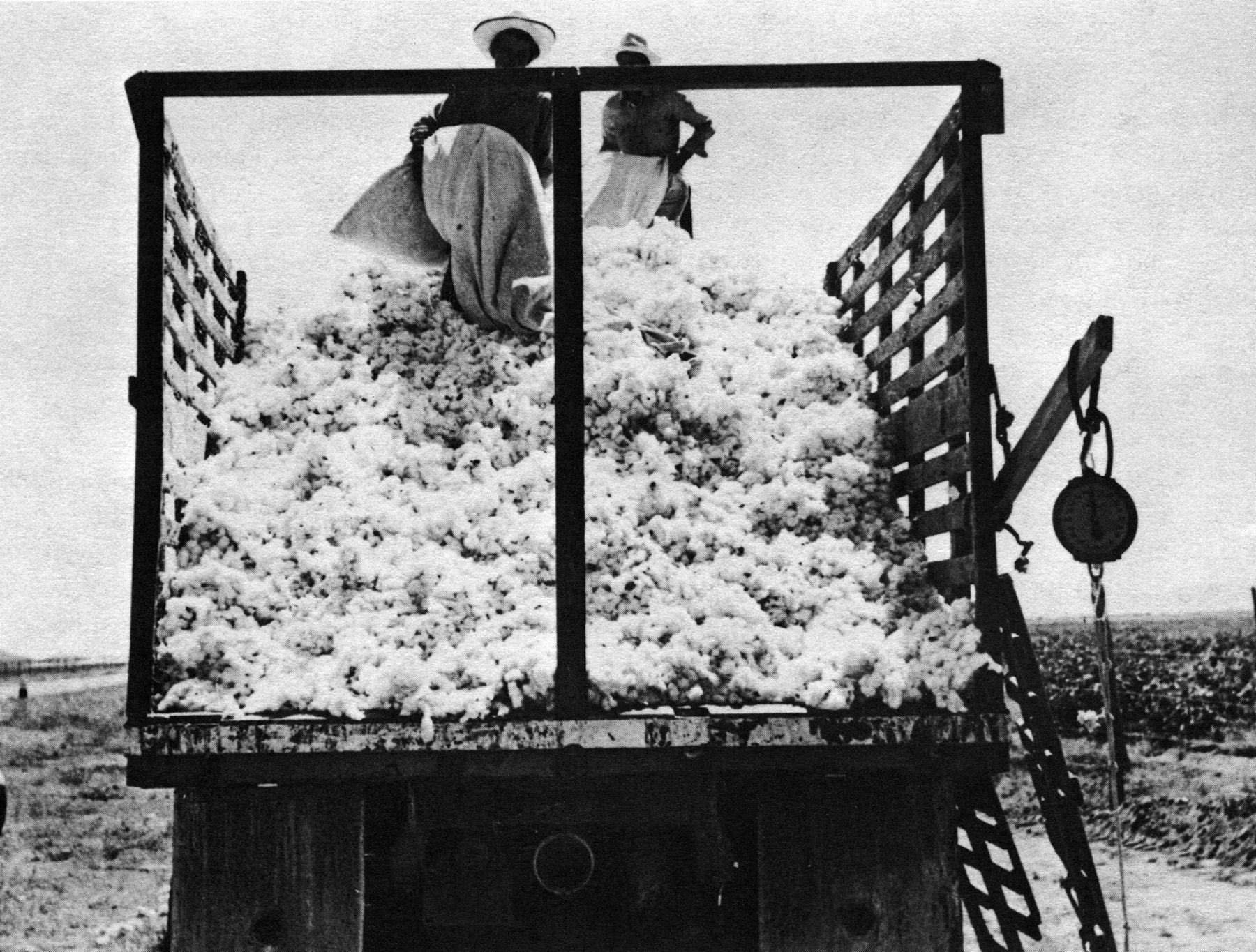

By the time Johnson was a teenager, Lobo flats were home to some 60 water wells irrigating an estimated 7,000 acres. The fields filled with everything from cotton and sorghum to lettuce and alfalfa. Johnson remembers towering trees bordering their crops.

“Now there’s a bunch of fallen wood,” says Johnson during his hike through the flats. “The willow trees kind of split in the middle, so it’s sort of religious to see the way they fell. They fell in all angles from the center.”

After years of aggressive pumping, a state board estimated the water table under the flats had dropped by 70 to 90 feet. Soon, Lobo’s cotton gin closed. Its post office was shuttered. And by the 1980s the last of the farmers had left. For nearly two decades it was quiet.

Then came the Germans.

“It’s really a ghost town,” says Axel Roessler, who is now a part owner of Lobo. “Basically what we bought is the stones and the sand.”

Roessler’s friend Alexander Bardorff, a bartender from Frankfurt, Germany, saw the town was for sale during a visit to Texas in the ‘90s. “So at one point he came back from the U.S. and said, ‘OK I bought it!”