From KERA News:

Cassie Weddel can’t express herself through words, but she can express herself through her surprisingly strong grip. She’s always reaching for her mom’s hand as they sit in the family living room in North Richland Hills.

“Cassie loves to grab and hug,” her mom, Lea Ann Capel, laughed. “Sometimes to the point where she’ll pull you over.”

Almost 38 years old, Cassie needs round-the-clock care, Capel said. Her physical and intellectual disabilities mean she can’t walk, brush her teeth or bathe herself, and doctors estimate she’s at the cognitive level of a toddler.

In a family where everyone works, that type of care is impossible to provide at home without support. That’s why, in 2008, Cassie moved into a group home 10 minutes away from her mom’s house.

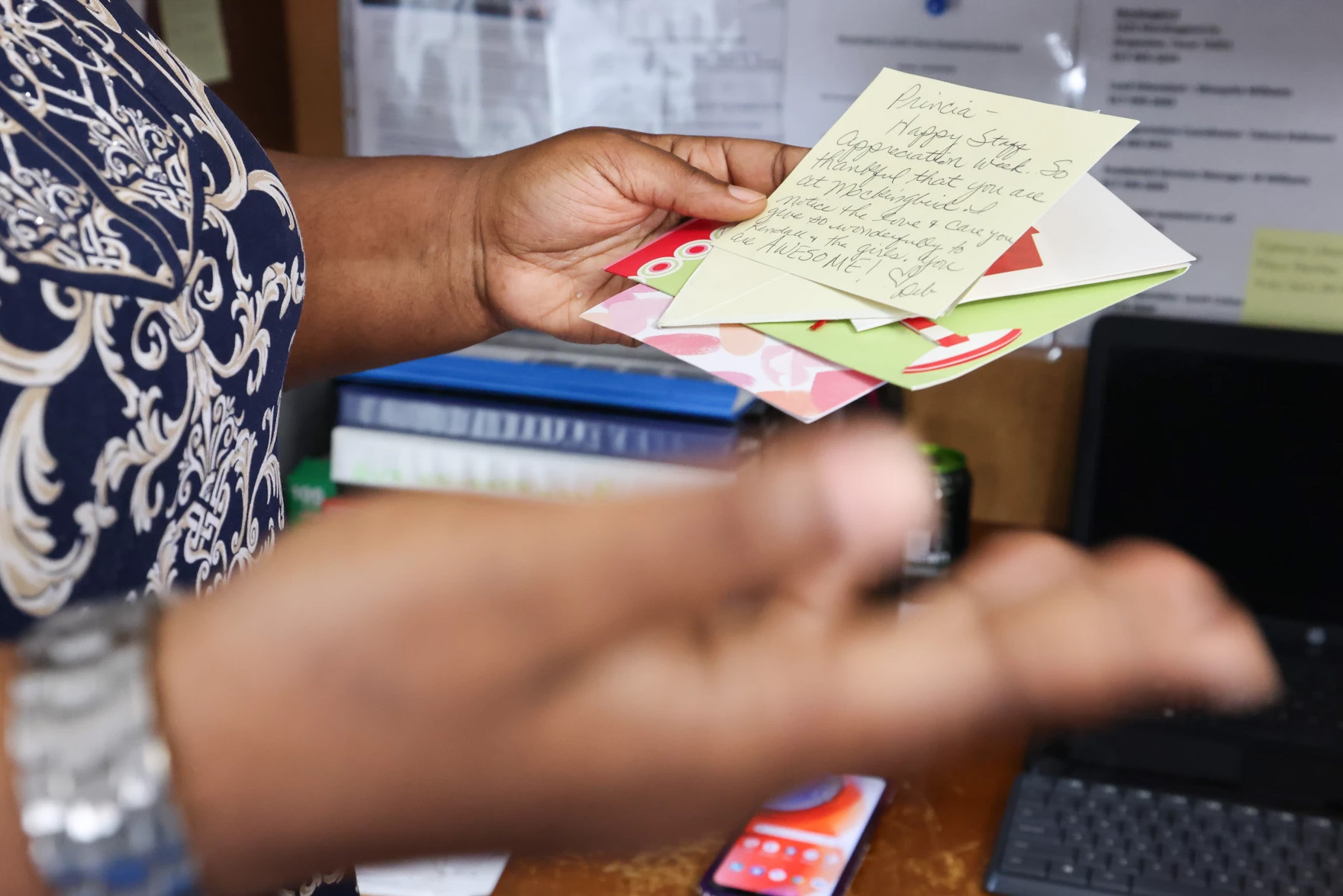

Group homes are normal houses where people with intellectual disabilities can live, supported by staff called direct care workers. They do just about everything: cook, clean, give out medication, and make sure residents are happy and healthy. Group homes are an alternative to living in a big state institution, and a way to keep people with intellectual disabilities in the community, closer to their loved ones.

For years, the group home was great for Cassie, Capel said.

“Until recently,” she said. “And that’s when things started to become concerning.”